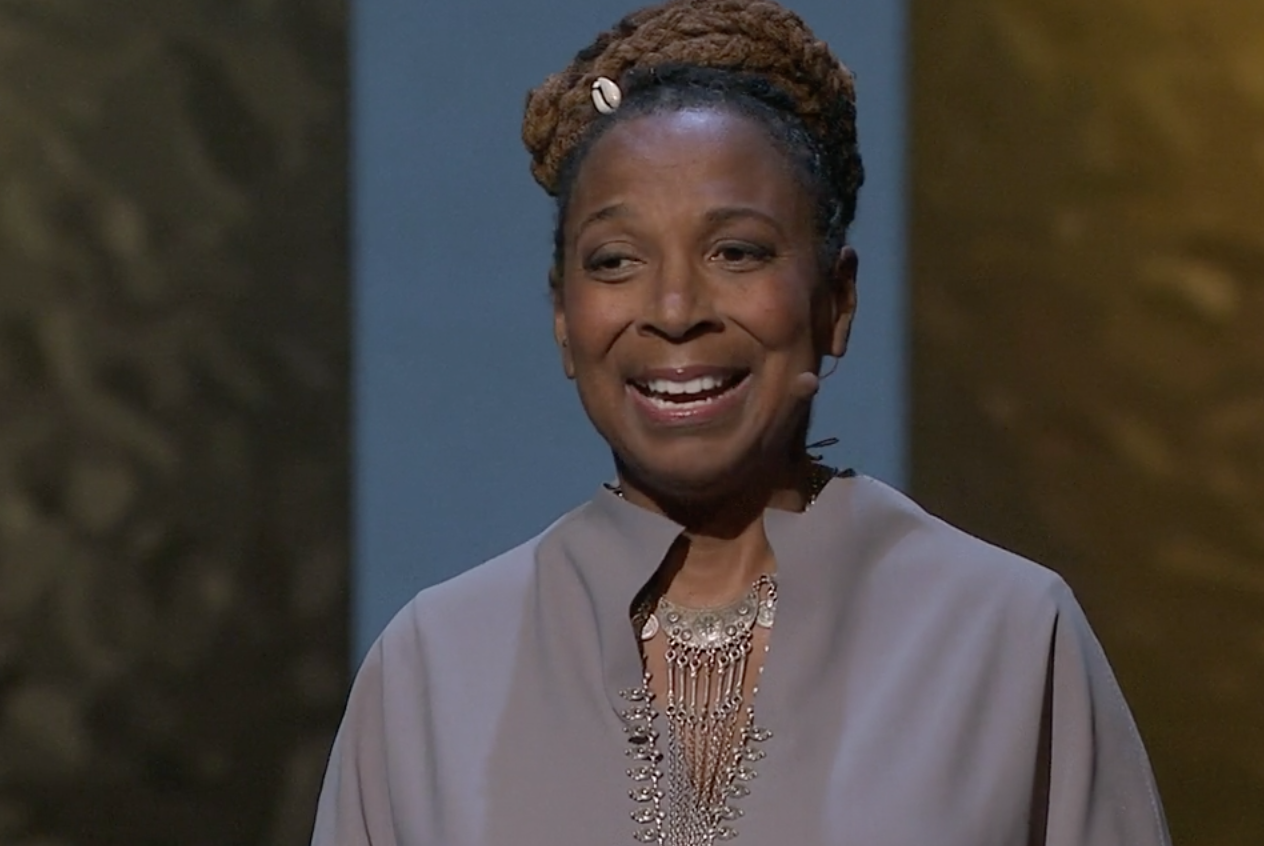

Feminist Theorist Thursdays: Kimberlé Crenshaw

Image by TED.

Now a professor of law at UCLA, civil rights activist and critical race scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw formally introduced the term intersectionality to feminist theory in her 1989 essay “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” Her primary motive was to highlight the way in which black women are erased from black politics and (largely white) feminism, and thus to employ intersectionality in service of making black women visible. Crenshaw intended intersectionality to challenge the failures of feminist and anti-racist discourse in addressing the experiences and struggles of women of color.

Identity has always posed a philosophical problem. The two major ideological camps, essentialism and social constructionism, theorize identity in opposing ways. Essentialism proposes that a social category or group has intrinsic, stable meanings and experiences common to that category and its ideal. Essentialist thinking gives these “group universals” precedence and legitimacy at the expense of more marginalized and complex identities. This erases and crushes the subtle differences of social experience. For example, the experience of woman becomes that of the bourgeois white woman.

On the other hand, social constructionism theorizes identity as an empty and meaningless abstract concept. Categories like race or gender have no inherent truth because they are culturally and ideologically produced. While this may be true, social constructionism sometimes obscures the way in which identity is grounded in material reality. When taken to its vulgar extreme, this sort of constructionism becomes apolitical and oppressive. For example, a social constructionist could argue that because race is a social construct and it is made up, the experiences of people of color have no validity. The proponents of these arguments tend to forget that just because an identity is socially constructed does not mean it has no real, political consequences. As such, neither essentialism nor constructionism sufficiently analyze the complexity of social life and oppression.

Crenshaw’s intersectionality provides a theoretical and practical alternative to apolitical constructionism and oppressive essentialism. While Crenshaw focuses on the cross-sections of race and gender in her work, she argues that many other factors, such as class, sexuality, and ability are just as critical in distributing social power and producing grids of oppression.

Intersectionality relies on social constructionism at its foundation because it understands that individual experience consists of socially constructed, intertwined, and inseparable aspects of identity. This makes intersectionality anti-essentialist. But it bypasses the pitfalls of extremist constructionism by recognizing that these constructed categories still have social and political significance. Intersectional analysis locates identity within a matrix-like structure of overlapping and inextricable linkages: the different aspects of identity (i.e. race, gender, class, ability, sexuality) interconnect to produce the self. These aspects cannot be evaluated individually. Intersectionality thus allows for a much more accurate understanding of social existence because it functions according to a mapping process, tracing and re-tracing the nuances of social oppression as they shift and interact.

In her 1991 essay, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color,” Crenshaw writes that the “failure of feminism to interrogate race means that the resistance strategies of feminism will often replicate and reinforce the subordination of people of color, and the failure of antiracism to interrogate patriarchy means that antiracism will frequently reproduce the subordination of women.” In short, a non-intersectional approach in political resistance tends to alienate more marginalized identities and reinforce oppressive measures.

In light of the Trump regime’s past few weeks in office, we must once again revisit Crenshaw’s theoretical contribution to make sure our political activism does not replicate harm against marginalized peoples but rather positions the most vulnerable at the forefront of our fighting and protest.

For example, the stricter control of reproduction following the reinstitution of the Global Gag Rule, which defunds abortion-providing organizations, will have the most harmful effects for black women in poor countries, particularly in the Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa. Immigration raids target Mexican and Latinx peoples while undocumented white immigrants go largely unscathed. Transgender women are most likely to suffer from hate crimes and sexual violence, and transgender people of color are most likely to experience police violence. At the Women’s March this past January, the rabid biological essentialism of many participants and emphasis on genitals alienated many transwomen and left them feeling unsafe.

Right now, it is absolutely necessary for cisgender feminists to fight for transwomen before ourselves. This is especially pertinent since radical feminists recently allied with the Christian right to combat Obama’s bathroom mandate that allows transgendered individuals bathroom access in federal facilities. We must place the struggles of black women at the forefront of our feminism. Financially secure women must fight for poor women first. We must all align against the police and federal agents, we must all organize and act in communion against capitalism. Our feminism has to be intersectional or it isn’t true equality, which is what feminism is all about.

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s contribution to feminist politics has not been only theoretical. While ivory tower academics are typically politically inactive or elitist, Crenshaw has a history of civil rights advocacy and activism. She has campaigned extensively to raise awareness about the specific institutional racism against black girls and formally organizes alongside black women for the African American Policy Forum (AAPF). She is a living reminder that feminism is about doing, about coming together and fighting against structural and systemic modes of oppression. Kimberlé Crenshaw embodies intersectional feminism, and that is precisely what each and every one of us must do in order to actualize political change.

You can follow her on twitter here.