We Are Not Apologies

The language of entitlement and resulting dialogue not only wrap around the body, forming a constricting outer film that chokes the skin underneath, but attempt to co-opt perceptions of self-worth and substance. The belief that it is both acceptable, and in many cases necessary, to comment on the state of the female body speaks to an underlying assumed privilege that runs rampant among both genders. While both women and men feel comfortable critiquing the clothes, make-up, and overall appearance of other women, I am still surprised by the constant compartmentalization of my body.

As my body has been broken up into portions of my face and little pieces of my anatomy, the clothing that hangs-upon my body has also been judged as an articulation of the “person” underneath. I am coming to realize that this isn’t a “phase” I can simply age out of, but a life-long experience that I am expected to put up with for fear of upsetting a precarious equilibrium of objectification and silence.

At sixteen, I was not sure why my driving teacher felt comfortable telling me that he would never let his daughters wear what I was wearing, but at twenty, I understand why both women and men feel some sort of pull to comment on or judge my appearance. As the female body is consistently and forcibly bound to a socially constructed ideal of beauty and “respectable” outer presentation of self, I understand the need to police my appearance as a manifestation of dominance and control that I am supposed to shrink beneath. While society has constructed an exemplar of feminine beauty and modesty, inextricably tied to the silencing of the female voice, the implications of a woman who stands against her given “lot in life” threaten to dismantle a standard of treatment that has been normalized with subtlety and disguised value distinctions.

A woman’s worth is not the resulting product of an equation of body, clothes, and make-up; but the words “too much” and “too little,” when attached to the body, are meant to systematically assess and categorize the quality of the individual.

Sometimes, the judgments and resulting equations of worth are not as indistinctive, but so explicitly offered that I have to re-evaluate what I expect out of conversations and encounters with strangers. While leaving a concert, two men called out to me that I needed to “dress my age” and wear “higher heels” if I wanted to be “sexy.” They were apparently nonplussed by my “heel-less” shoes and hoped I would take their advice so I could be more easily digested by their eyes. More recently, as a male stranger at a party asked me if he could provide advice, following with the words “guys would be a lot more attracted to you if you wore less eyeliner,” I was momentarily silenced in a daze of disbelief. I thought of my eyeliner, the small amount of glitter around my eyes, and immediately caught myself trying to quantify amounts of acceptable makeup.

I knew he was wrong in feeling the right to speak to me in such a way, but I was almost prepared to mentally counter his argument with “it’s not that much makeup.” This inclination towards self-critique and projection of an appropriate appearance betray a socialized desire to deflect from “me,” to an ambiguous but universal “her.” This “other girl” that presumably wears more makeup than us and dresses less respectably than us, is the same “girl” blamed for promiscuity and for presenting herself as a willing victim. The frequent assumption that this “other girl” is unrelated to us and that we are only briefly confused with “her,” exemplifies a prevalent logic that seeks to dislodge a collective experience from the isolated dialogues of entitlement that catch individuals off-guard. There is not a level of too much makeup and there is not a limit which defines too little clothing. There is no “that girl,” that invites critique and deserves what she gets.

While I cringed when a group of men called out to me on the street and told me I was “too ugly to talk to anyways,” I experience the same feelings of disgust when cliques of women and/or men talk about “that slut” that passed them on the street or walked into the party. When appearance is wrongly marked as a defining characteristic of individuals, the entitled voices that yell out into the night or speak quietly so that the “othered” cannot hear, do not expose any failing but their own.

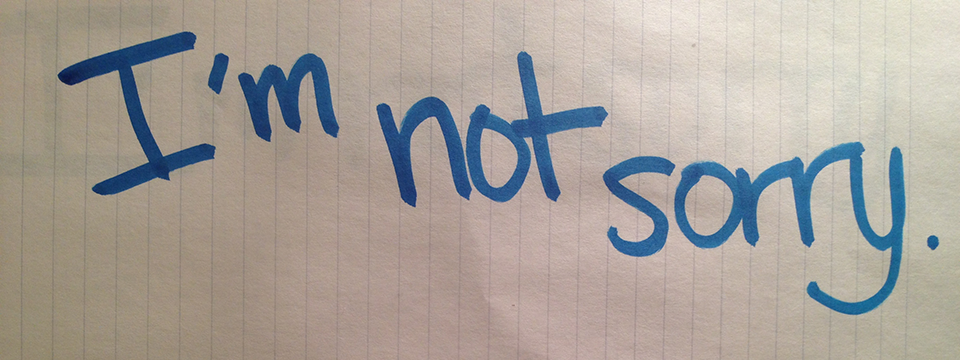

The constructed discourse of entitlement seeks an apology from the women being addressed. Apologize for your weight, your proportions, your hair, your make-up, your clothes, your skin-color, and your perceived social-class. Apologize for your confidence or lack thereof, for your laugh, for the way you walk, and for the time you decide to go out at night. Apologize for being a “willing” victim who solicits commentary and/or assault. Apologize for being. But, the voices and bodies of women should not be bound to the speeches and presentations of regret.

We are not apologies.