Is Only Paris Worthy of Prayer?

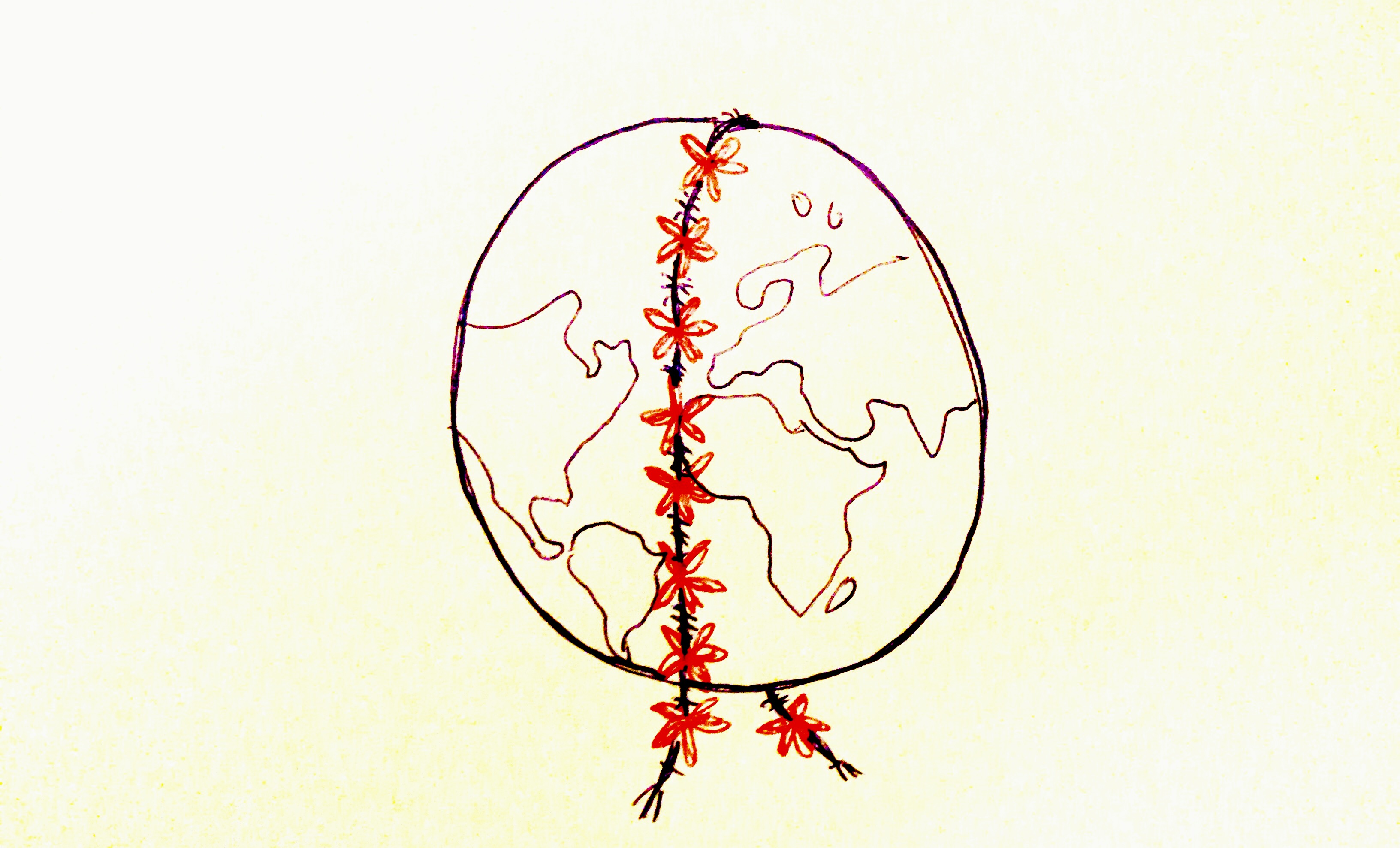

Illustration by Tulika Varma

On Friday, 13th November, a series of seemingly-coordinated terrorist attacks ripped across six locations in Paris, killing 129 and wounding hundreds. The day after, ISIS claimed responsibility for all of them. Facebook was quick to activate Safety Check, a feature that allows users to mark themselves as safe and notify their friends. They also introduced a French-flag filter for users’ profile pictures as a mark of solidarity. Monuments around the world lit up in red, white, and blue. Prominent politicians issued statements and tweets expressing their shock and sending their condolences – Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Angela Merkel, and Malcolm Turnbull were amongst them. Media outlets set up live blogs and are churning out wall-to-wall coverage of the attacks. The hashtag #PrayForParis has gone viral.

Of course we must pray for Paris – the senseless loss of life is always confounding and terrifying. But I urge all those of you who are watching the videos and changing your profile pictures, to question the nature of what you are being shown on social media and otherwise. Just a day before these attacks, Beirut was terrorized by a double suicide bombing that killed about 43 people. As Paris went down, Lebanon was emerging from a National Day of Mourning. Did we see a red, white, and green filter on Facebook? Did we see the hashtag #PrayForBeirut?

I am in no way suggesting that we lessen the magnitude of one tragedy to highlight another. Human lives have the same value everywhere – but that is exactly what the media and those who consume it fail to realize. In the past few months, the loss of life in non-European nations has been staggering. 147 died in a Kenya school shooting in April. 54 killed in a mosque in Nigeria at the hands of Boko Haram in September. 26 killed by a bombings in Baghdad on Friday. 43 in Beirut on Thursday. Hundreds of civilians die every single day in nations that are still torn apart by Western imperialism. Muslims are more likely to die at the hands of extremists and also more likely to die at the hands of Westerners trying to kill those same extremists. Unlike the Parisians who lost their lives on Friday, the people in nations where the state of war is permanent, live in perpetual fear.

But that does not qualify them for some higher award of martyrdom. My issue is with the disparity with which these events and the events in Paris have been covered. My issue is with the silence that meets the loss of black and brown lives. My issue is with how the loss of (primarily) white lives is somehow deemed more appropriate for continuous press coverage and Facebook-endorsed sympathy.

On Friday, the Western world got a glimpse of the terror that millions endure every single day without global support and solidarity. And yes, they deserve our prayers. But we must always, always keep in mind the prolonged suffering of generations of people of color, and offer them the support we can because they are still devalued and dehumanized today today, when most people like to think that war and suffering are things of the past, that we are some great post-war world. The erasure of their suffering upholds the idea that white lives matter, and the other ones don’t. Alex Schultz, Facebook’s vice-president of growth defended their decision not to activate the Safety Check feature after the Beirut blasts, stating that it is “less useful” in war-torn regions because it is “impossible to know when someone is truly safe.” But the people in those regions still deserve to know their loved ones are safe when incidents of that magnitude happen. President Obama called the Paris attacks an “attack on humanity” – but we should question who gets to be human. Why do we hand out humanness selectively? The New Yorker wrote that there is a “will in France to not be turned into a citizenry that does not recognize itself.” But having the ability to recognize your own humanity is not something you are guaranteed, but something that is handed to you, and thus, can be taken away. Recognition, and therefore sympathy, is a privilege that in our world, we have taken away from people of color who need it desperately.