Healing from Sexual Trauma

Image: La Shonda Coleman from the Santa Monica Rape Treatment Center, photo by Jacqueline Pei.

The last event of Bruin Consent Coalition’s Consent Week was the Neurobiology of Trauma, consisting of multiple presentations to help guide the healing process for survivors and friends of survivors of sexual assault.

Healing is a complex and different process for each survivor, since the nature and consequences of sexual assault exists on a continuum. Trauma can come from any perceived or realized threat to one’s safety, including catcalls, street harassment, unwanted sexual conduct, and vaginal or anal penetration.

That being said, sexual assault on every point of the continuum must be confronted. The most common form of sexual assault, catcalling, is experienced by 84 percent of women before they turn 17. Every catcall must be battled, for no act of sexual assault is isolated. “It’s important that we address verbal sexual harassment, because we understand that if we don’t address it, fix it, that it will create a culture where physical forms of sexual violence happen and it’s minimized or excused or ignored,” says La Shonda Coleman, the Director of College Programs at the Rape Treatment Center in Santa Monica.

Therefore, it is our responsibility—as peers, friends, family members, co-workers—to actively address sexual assault at all points on the continuum if we are to make a lasting change in a culture that normalizes rape. Rape culture is toxic and deeply embedded in our everyday interactions, and La Shonda further unpacks its implications for gender: “It’s a culture where the feminine is devalued, and that has implications not only for those who identify as female, but for all gender identities. It limits who we are, our gender expression. It sets up expectations for how we are to engage with one another. Those expectations can form behaviors.”

Those behaviors form a continuum of sexual assault that is normalized and result in a range of physical, mental, and emotional trauma that is suppressed. La Shonda explains the silent danger of rape culture on survivors of sexual trauma: “Survivors of a sexual trauma may not realize what happened was traumatic. They may not label it as such. and by not labeling it as a traumatic experience, rape, sexual harassment, or another form of sexual abuse, it may cause the survivor to be reluctant to seek support. And as they are hesitant to seek support or define their experience, they’re still experiencing the trauma in their body. Whether it’s just feeling disconnected from other people, or feeling numb, or feeling hypervigilant. They may experience moments where their heart is just racing, and they don’t know where their anxiety is coming from.”

The effects of sexual trauma can stay in the body, neglected by the outside world, which is why La Shonda advocates for the importance of “creat[ing] this context to understand that for survivors of trauma, there’s all these reactions that they’re working through on their own. But then in the context of our community and our culture today, the trauma can be furthered, or create a barrier against healing.” Thus it is vital to eradicate rape culture and have trauma-informed communities that can work together with survivors through the healing process.

“Trauma is a deeply disturbing or distressing experience. It’s really too much, too fast, where normal methods of coping are not accessible. Complex areas of the brain responsible for controlling and modulating our reactions are compromised,” explains La Shonda. As the complex thought processes shut down, our basic human instincts are mobilized by our sympathetic nervous system: fight, flight, or freeze. La Shonda emphasizes that “it’s an unconscious response. It’s about survival.”

Thus, it would be inhumane to blame the victim of sexual violence. In a traumatic moment, there is nothing they can do but survive, through whatever means their brain has decided as the best method of survival. If there is perceived threat, perceived danger, our survival mode instincts are mobilized by our nervous system and we are no longer in control.

La Shonda describes situations where “someone who is experiencing sexual trauma may want to run, may want to scream, may notice that they have several friends next door that can help them, but they’re stuck. They’re in freeze mode. They don’t do anything. Because the brain, the amygdala, has assessed the safest thing to do is just freeze. Just freeze. Just survive this moment. And a part of that freeze may be dissociation where our bodies are there, but mentally, emotionally, it’s just numb.”

The freeze response comes with a set of post-trauma symptoms that make the healing process difficult. It can impact memory so that they cannot remember everything that occurred. The response can extend further by leaving them feeling disconnected from the actual assault, leaving themselves emotionally and mentally numb even after it’s occurred.

But the damage from the trauma our minds block out often reveals itself in medically unexplained physical symptoms. “We all have this window of tolerance, this ability to function even when there is a trigger or a trauma,” La Shonda says. Usually, even when there are anxious or stressful situations, we manage to remain in our window of tolerance. But “when something like rape or another form of sexual assault happens, one is bumped out of that window of tolerance.” Even if the freeze response has further numbed the victims emotionally and mentally, symptoms of the trauma can reflect physically: hypervigilance, high heart rate, difficulty breathing, muscle tension, difficulty sleeping, fatigue, headaches, stomachaches, and other somatic symptoms that present physically that is not technically medically-induced, but rather trauma-induced.

It’s an important first step for survivors and for friends of survivors to begin healing by recognizing that all of these symptoms make sense, that our bodies are wired to react this way after a trauma. But it’s equally as important to remember that there is hope, that they can be knocked back into the “resiliency zone,” where the body of the survivor is not constantly in a state of unconscious fight, flight, or freeze.

In the same way that physical symptoms will vary, emotional reactions to sexual trauma will also vary, says La Shonda. Sometimes people will feel stuck emotionally, unable to access their feelings, until some moment when their emotions may just flood in. Survivors’ emotions can be subtle, and sometimes it can be as intense as shock. They can feel a sense of shame, confusion, and/or anger.

But whatever they feel, however they react, “there should be no expectation of how survivors should feel,” La Shonda stresses. They feel what they feel because their brains are doing what it can to protect the survivors’ ability to persist.

Sexual trauma is a deeply intimate crime of humanity, and survivors may often have difficulty maintaining or making new relationships. Sexual assault is an abuse of trust in the context of a relationship, however close or distant that relationship is.

But La Shonda offers hope for survivors by explaining, “In the context of a healthy, safe, nurturing relationship, survivors can experience healing and there can be a laying down of new neural pathways where [the relationship] is not connected to the trauma or the abuse. It can be connected to the sense of safety, or other pleasant memories.”

Lauren Marlotte, a clinical psychologist at the Semel Institute, also emphasizes the importance of open, comfortable, and effective communication, as well as some other advice for survivors to help cope after a traumatic event:

- Doing the best to follow some sort of normal routine. It can be something as small as making breakfast in the morning or watching a TV program at a certain time of day.

- Talking about it with a person you feel comfortable, safe, and open with. Re-building a sense of safety and comfort with the people around you is critical to recovering from a traumatic event.

- Taking a break from talking or thinking about it. Give yourself the time and care that you need.

- Journaling has been shown to be incredibly healing and enriching. It can help access parts of yourself you may not feel comfortable sharing with other people.

For those who have a close relationship with someone who has endured a sexual trauma, be mindful of communicating with them. It’s important to let them know that they can trust you with their emotions, so La Shonda suggests loved ones to be aware of nonverbal cues when survivors discuss their experience, to not make promises you cannot keep, to not judge or blame them, and to nurture their broken sense of agency by allowing them to make their own decisions.

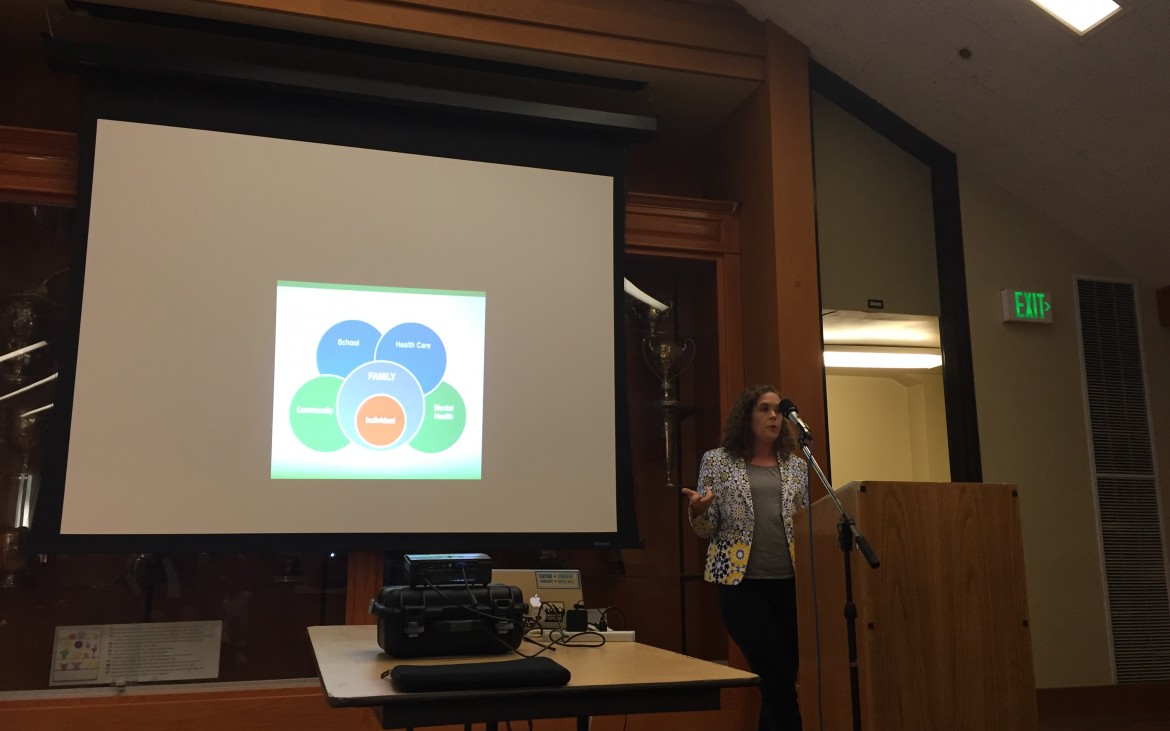

“Individuals do not exist in a vacuum,” says Lauren. As a family, school, and community member, we all play a role in promoting consent culture to aid the healing process for the survivors walking among us and to prevent sexual violence and the trauma that follows.

This united effort comes in the form of consent education and a consciousness of the repercussions of rape culture and sexual trauma. Thank you Bruin Consent Coalition, for hosting an informative and effective Consent Week 2016!