Digital Blackface

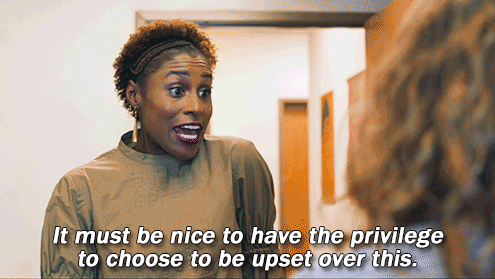

image credit to HBO Entertainment via HBO

Up until a few months ago, I had not heard of the term “digital blackface” in any of my academic or social circles. But the moment these words were introduced into my vocabulary, I immediately understood what they meant. The most common examples of digital blackface are memes and GIFs of black people (children, women, athletes, etc) used to describe a non-black social media user’s experiences, emotions, or reactions to a given occurrence.

In a matter of seconds, one can type a word into Twitter’s GIF search function and find an extensive collection of reaction GIFs that would adequately describe one’s experience. Yet the GIFs that seem to receive the most social media attention are those in which black people behave dramatically and confirm stereotypes about what it means to be black.

For frequent social media users (like me), digital blackface makes up a great amount of the content that we interact with. In the past few years, I felt a growing sense of personal discomfort as this trend escalated on social media timelines, but lacked the words to articulate why these images made me uncomfortable. My friends and I have discussed our shared uneasiness when it comes to digital blackface, which we constantly interact with on Twitter and Instagram, yet we didn’t fully understand why it makes us upset.

Was it because the subjects of these reaction memes are often black women occupying stereotypical roles and behaviors? Or maybe because of the infuriating, anti-black history of minstrel that taints U.S. history? Ultimately my anger boils down to the ways in which the average non-black social media user is unfamiliar with the greater impact of their actions, regardless of intent.

It is crucial that Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram users understand that digital blackface does not exist in a social media vacuum; rather the painful legacy of blackface — as just one agent of White Supremacy — must be considered in order to grasp the depth of this issue.

Historically white minstrel actors modified their appearances and behavior in order to perform racist interpretations of what it means to look, sound, and be black. These actors often applied dramatic makeup in order to darken their skin and enlarge their lips, reflecting demeaning stereotypes about black people that often characterized them as unintelligent and animalistic.

Minstrel set the precedent for modern-day blackface, the kind that we see at college parties and get into Twitter fights about while watching Dear White People. Although not all members of society necessarily condemn these offensive and violent practices (because they certainly continue to happen), there seems to be a general understanding of blackface as an offensive practice.

So, if a growing number of non-black Americans can agree that painting one’s skin brown or black and throwing up a gang sign is not only inappropriate but also blatantly racist, why should we as a society view digital forms of blackface any differently? Sure, the format of blackface has changed, but impact in 2017 remains the same.

I spoke with UCLA sophomore Nyla Williamson about her experience dealing with digital blackface, which she described as non-black people’s problematic attempts to “impersonate blackness.” Williamson, a black Gender Studies and International Development Studies double-major, most often observes this phenomenon on Twitter.

In our conversation Williamson critiqued the misuse of black slang and visual culture on Twitter by non-black people, specifically white gay men. “That does not sound right coming out of your mouth,” says Williamson to those who appropriate African American vernacular in their social media platforms.

Digital blackface isn’t necessarily about consciously hating blackness. In fact, it is my experience that most non-black social media users are often working to emulate an aspect of black culture (based on their interpretations of blackness) that they find amusing or cool, rather than one they dislike.

As part of a larger conversation about intent versus impact, however, these very people should be able to distinguish between praising or celebrating blackness and impersonating it. The latter contributes to the caricaturization of blackness and trivializes black people’s experiences as amusing, entertaining, and performative instead of complex, authentic, and diverse.

“Black people are not here for other people’s entertainment,” stated black British writer Victoria Princewill in her BBC clip about the rise of digital blackface. Princewill challenges the two-dimensionality that is assumed of and prescribed to blackness in all practices of blackface. She describes digital blackface, specifically when “white people use GIFs to perform some sort of exaggerated blackness,” as the “21st century version” of minstrel shows.

When a non-black person takes on a black persona in their social media profiles or bases the entirety of their social presence on black reaction memes and GIFs, they contribute to the commodification of blackness. The fetishization of blackness in this scenario is enough to make any socially conscious person uncomfortable through its blatant misuse of blackness as a means of gaining social capital. To minimize an entire people by warping their history, culture, and individual experiences into a series of racist tropes or archetypical behaviors for the sake of entertainment is dismissive and violent.

Having addressed this issue within black communities and spaces at UCLA, I acknowledge the difficulties of discussing digital blackface outside of my social circles. Moving forward, however, American society would benefit from addressing the complexities of digital blackface given the violent history (and present day existence) of anti-blackness in the United States.