Portrait of the American Gun Owner

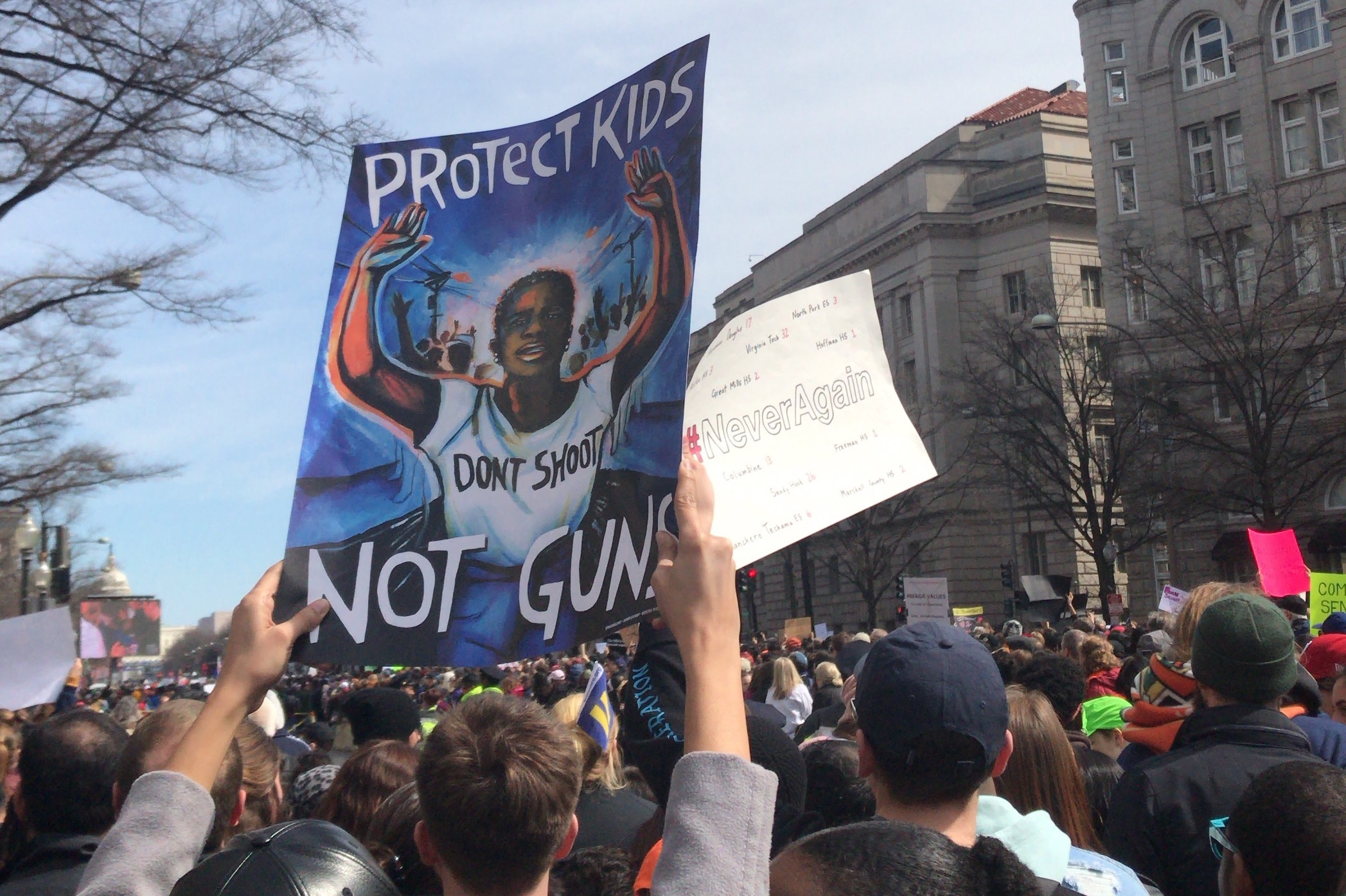

Photo taken at the March for Our Lives in Washington, D.C. courtesy of Maya Khuzam

Who is the quintessential American shooter?

It might be Dylann Roof, the Confederate flag-waving white supremacist who interrupted a summer church service in Charleston to kill nine African Americans mid-prayer. The setting of this mass shooting rendered the litany of “thoughts and prayers” offered by politicians particularly hollow. Not even Roof’s manifesto stating his goal of igniting a race war convinced the FBI to apply their label of “terrorist.”

Or maybe it’s Stephen Paddock, the Las Vegas shooter who used bump stocks to commit the deadliest mass shooting in American history from a hotel balcony. Paddock abused his Filipina immigrant girlfriend, Marilou Danley, further demonstrating the intimate and entirely predictable link between domestic and public violence.

Or perhaps we should look farther, to the origins of the Black Lives Matter movement, which situated the vague threat of “gun violence” in the long history of state-sponsored violence against black people. George Zimmerman is the perfect product of the neoliberal American State: as a self-appointed neighborhood watchman, he assumed the responsibility of policing his white neighborhood from foreign (nonwhite) elements and shot 17-year-old Trayvon Martin on the sidewalk. Zimmerman used a legally purchased handgun and was acquitted of second-degree murder in light of Florida’s stand-your-ground law.

Florida, then, might be the epicenter of our gun culture, as America follows students into the streets to call for stricter gun control legislation in the wake of the Parkland, Florida high school shooting. The 800-city March for Our Lives on March 24 was the largest student-led protest since the Vietnam War. At the eye of the storm of national debate is the Second Amendment, pitted against our children’s lives: Columbine. Sandy Hook. Marjory Stoneman Douglas. A new school every week.

In our eagerness to use these recent tragedies as a platform to galvanize the passage of gun control legislation, we should be careful to avoid a singular focus on children’s safety in our advocacy. This ignores the vast historical context that makes gun ownership a racialized and gendered privilege. Mass shootings account for only one percent of all gun deaths, and they are only one manifestation of the pervasive gun culture that serves to subjugate the marginalized in the neoliberal State. Like all social justice movements that reach the mainstream, gun control rhetoric faces the danger of echoing the very oppressive ideologies it seeks to challenge.

In her 2017 book, “Saving the Security State,” feminist scholar Inderpal Grewal calls the shooter “a subject of white racism, nation, empire and lethal heteromasculinity, one whose sovereign right to kill is enabled by the US security state.” She argues that the contemporary shooter is a product of neoliberalism — as the state shrinks and the labor of maintaining society becomes an individualized responsibility, the shooter becomes a vigilante who upholds the boundaries of national identity and citizenship. This partially explains “gun-rights” activists’ obsessive fixation on personal liberty and their insistence on interpreting the Second Amendment as an individual mandate.

It was Ronald Reagan, the father of American neoliberalism, who enacted the country’s first gun control laws. In 1967, then-Governor of California Reagan signed the Mulford Act, a bill that banned public carrying of loaded firearms. It was no secret that the bill targeted Oakland’s Black Panther Party, which operated armed civilian patrols in its neighborhood to monitor police brutality against Black Americans. Gun control was born from a fear that Black people with guns threatened the lives of white men and the sovereignty of the State.

To this day, the right to self-defense with a gun is selectively applied. Stand Your Ground laws allow shooters like George Zimmerman to disguise racism in the justification of mere threat. Stop-and-frisk laws offer police an explicit license to racially profile, encouraging them to stop and search a person for weapons if they have “reasonable suspicion.” In 2016, Philando Castile, a Black man, told the police officer who pulled him over that he had a licensed firearm in the car. When Castile reached for his ID and registration, the officer shot and killed him in front of his girlfriend and four-year-old daughter. When asked about the death of this legal gun owner, an NRA spokeswoman pointed to Castile’s possession of marijuana and said he shouldn’t have been moving his hands.

I am reminded of a gun control panel at UCLA last year where I asked a white, male NRA lobbyist to address the fact that gun ownership often incriminates rather than protects people of color. After a moment of flustered blinking, he proudly answered, “The NRA doesn’t consider race. We do our jobs for everyone.” It is precisely this deceptive, willful “colorblindness” that allows defenders of “gun rights” to spin their propaganda in the neutral language of individual liberty.

This reality does not mean that gun control laws are inherently racist. It does mean that we can’t talk about guns without also discussing who has had the historical privilege of holding them.

Public debate about gun violence that does not name the U.S. security establishment as its foremost perpetrator only entrenches the concept of police brutality as outside the boundaries of problematic gun violence. Gun violence perpetrated by those in uniform enjoys the legitimacy created by state support, which makes abuse largely invisible. 987 people were murdered by the police in 2017, a disproportionate number of them people of color. A variety of systematic oversights and legal loopholes make it exceedingly difficult to hold police officers accountable for excessive force. Arming the police is not a necessary evil; police in the U.K., Norway, Iceland, New Zealand, and the Republic of Ireland do not routinely carry firearms.

A number of Parkland survivors and parents across the country have stated their support for increased funding for school security as a mechanism to prevent school shootings. To the contrary, militarizing schools with heightened police presence and surveillance can actually decrease the safety of students of color. Black Marjory Stoneman Douglas students recently called a press conference to state their discomfort with the police officers who patrol their school following the shooting.

Armed campus security is incompatible with the gun control movement’s vision of “gun free schools.” The ideal result of the current gun control movement should not be a society in which police and state agents are the only ones armed.

Much of popular gun control discourse portrays shootings as exclusively public events, occurring at schools or movie theaters or places of worship. It frames violence narrowly as a large-scale, gruesome event, rather than a series of interpersonal abuses. This reproduces the patriarchal logic of the separation of public and private spheres, casting domestic violence as a separate issue unrelated to the gun control movement.

Some statistics: Of all the mass shootings since 1982, women committed only three. In 2015, 928 women were killed in the U.S. by male intimate partners, most of whom used a gun. Abusers with access to a gun are 400 percent more likely to kill their female partner.

Rebecca Solnit writes that when we use the term lone gunman, “everyone talks about loners and guns but not about men.” Violence is deeply masculinized and gun violence is a tool of control and subordination, therefore it follows that men use guns to keep women afraid. Our marches should be as much for children as they are for their mothers.

Grewal points to the “militarization of the patriarchal home,” which occurs alongside the militarization of the police force and the individual American citizen. The pro-gun logic of keeping weapons in the home to protect from intruders does not acknowledge the historical role of the home in drawing the boundaries of normative, white American citizenship, nor does it recognize that a gun in the home increases the likelihood of a resident’s death threefold. The gun owner is a patriarch, and he points the barrel inward as much as he points it outward.

It would take many more paragraphs to address our white Christian leaders’ hypocrisy in applying the inherently fascist term “terrorist” to Muslims but not to white shooters, as well as the sheer disproportionality of the War on Terror, given that foreign terrorism kills approximately one American per year and guns kill 96 Americans per day.

It is easy to talk about gun control in a vacuum. It is easy to imagine the Parkland survivors as wholesome kids who, as Emily Witt wrote in the New Yorker, “would have kept their heads down and scored high on their S.A.T.s” had the NRA just stepped aside and allowed Congress to ban bump stocks. “What about the children?” is low-hanging fruit in the movement to sway politicians and public opinion.

The teenage organizers of the March for Our Lives seem to understand that the issue they’ve taken on is bigger than Parkland: at the Washington, D.C. March for Our Lives, 11-year-old elementary student Naomi Wadler took the stage to speak on behalf of “African-American girls whose stories don’t make the front page of every national newspaper.” Two black Chicago teens walked onstage with tape over their mouths and fists raised, and then delivered a moving speech about systematic racism and poverty. Seventeen-year-old Edna Chavez, a Latina from South Los Angeles, led the crowd in chanting “Ricardo” — the name of her brother, who was killed by gun violence.

We cannot talk about “our children” as if they form a disembodied, singular unit, as if some children are not more likely to face the barrel of a gun than others. We cannot talk about AR-15s, automatic weapons, and high-capacity magazines without talking about the hands that hold them. And we cannot talk about the American gun owner without recognizing that he looks a lot like the American State.