Villainizing Bodies and Minds: Ableism in Horror Movies

Image via YouTube. / CC BY-NC 2.0.

Hollywood is an industry run on beauty by those the mainstream has deemed to be ‘beautiful.’ Visual mediums like film and television promote the socially constructed ideal of ‘perfection’ both physically and mentally. This image of perfection often boils down to someone who is cisgender, heterosexual, white, young, able-bodied and neurotypical. People with disabilities, both physical and mental, do not fit into this particular paradigm and thus often experience ableism and demonization in their portrayals in Hollywood features.

The horror genre in particular represents this form of ableism by characterizing its villains with disabilities as evil. This trope appears to be rooted in the conception that there is nothing ‘scarier’ to the able-bodied and neurotypical than those who are not physically and mentally similar to them.

People with physical disabilities have a long history of appearing in horror films as the antagonists, often against traditionally attractive, able-bodied female protagonists. The 1925 film adaptation of “The Phantom of the Opera” is an early example of this. The Phantom, played by Lon Chaney, has a face said to resemble a skull, as portrayed through Chaney’s makeup. The Phantom romantically obsesses over the female lead, Christine Daaé, to the point of killing for her. The film implies through this that the Phantom covets her beauty because his disability excludes him from traditional Eurocentric beauty standards.

Classic slasher series, like “Friday the 13th” and “Nightmare on Elm Street,” feature popular villains like Jason Voorhees, formerly a young boy with mental disabilities and hydrocephalus, and Freddy Krueger, a man with severe burns across his entire body. Both of these characters also go after young, beautiful women, though not for romantic reasons like the Phantom. They typically murder all but one woman, “the final girl,” for revenge or the pleasure of the kill. In this way, people with physical disabilities are popularized in the film canon as being violent ‘threats’ to women.

This trend has continued to persist in more current horror films like “Gerald’s Game” and “Don’t Breathe,” one showcasing acromegaly and the other blindness. While neither film perpetuates the traditional final girl trope, the disabled characters are still portrayed as antagonists victimizing women. Even though societal conceptions of female characters have changed over time, the idea that people with physical disabilities are ‘threats’ has remained untouched.

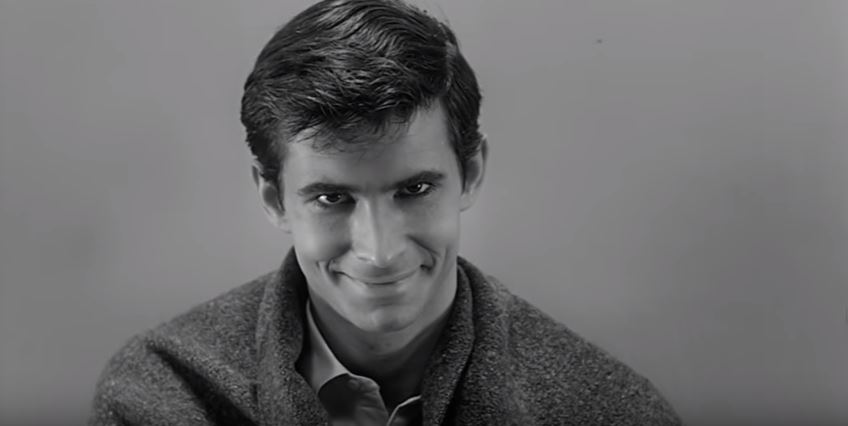

Characters with mental disabilities have not escaped this treatment either. Dissociative Identity Disorder, previously referred to as Multiple Personality Disorder, has repeatedly been portrayed in film as a sign of someone holding a secret evil identity within them. Such negative portrayals can be found in films like “Psycho,” “Identity” and “Split.” In each case, it is assumed that one of the identities must be a violent murderer. This depiction is problematic since people with dissociative identity disorder have often experienced past trauma and do not exhibit much criminal behavior in their present lives. Because they have a mental disability, these characters are demonized to contrast the neurotypical women they kill in their respective films.

Another popular horror movie character who demonstrates society’s stigma against those with mental disabilities is Michael Myers from the “Halloween” franchise. Although Michael is never given an exact diagnosis in the films, he is consistently locked away in a mental health institution. Dr. Loomis, the psychiatrist in charge of Michael’s care, states that Michael cannot be helped because he is a figure of pure evil. This can come across as confusing, because the film seems to say that Michael Myers does not have a mental disorder but is instead the living embodiment of evil. However, this actually seems more like a reflection of director John Carpenter’s views on the connection between mental disability and evil itself.

In the documentary, “Halloween: A Cut Above the Rest,” Carpenter states that his inspiration for the character of Michael Myers came from his college years, when he visited a mental institution for a class. There he saw a young boy who he describes as having “a schizophrenic stare…a really evil stare.” Carpenter embodies his opinion on mental disability through the character of Dr. Loomis, equating schizophrenia and other mental disorders with being truly evil and reprehensible. It also gives off the impression that schizophrenic people, as represented through Michael in Carpenter’s eyes, cannot be treated or possibly function in society in the future. By representing Michael Myers in this manner and having the young female lead Laurie Strode be in opposition to him, the usual dichotomies of good versus evil, virgin versus killer and neurotypical versus disabled come into play.

Despite studies existing on how disabled people are more likely to experience violence than able-bodied and neurotypical people, horror films continue to perpetuate the notion that people with disabilities are a threat to the safety of the public and particularly women who embody societal ideals of beauty and perfection. Recent movies like “Hush” and “A Quiet Place” have gone against this trope, both featuring protagonists who are deaf and not helpless victims because of their disability. This could be a sign of potential change in the genre and depictions of disabled people in cinema. However, with the return of Michael Myers to theaters in the 2018 version of “Halloween” and more potential horror reboots of disabled villains in the future, these ableist stereotypes still clearly persist in our pop culture consciousness.