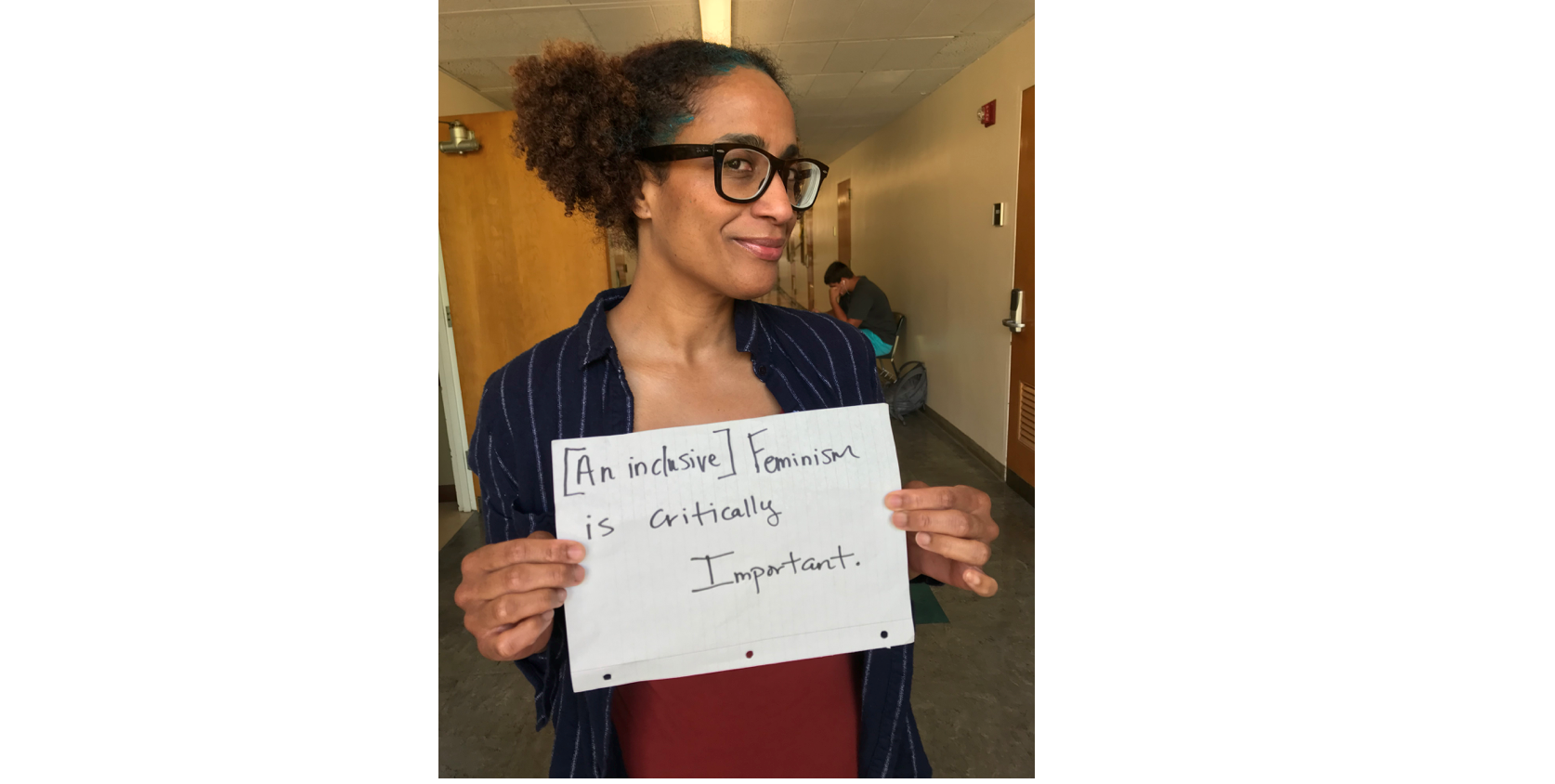

Featured UCLA Feminist: Erika L. Ganier

Photo by Jemina Garcia

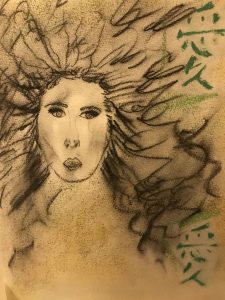

Artwork by Erika L. Ganier

Content warnings: mentions of sexual abuse, incest, suicide attempt

Erika Ganier is an artist. A super senior student majoring in English and minoring in film, Ganier has a strong audiovisual sense for beauty — she writes poetry, takes photographs, and sketches in charcoals and pastels. Her sense for the beautiful imbues everything she does with a visceral energy, as if to supernaturalize even the most commonplace thing with sensation and meaning. It’s what made me approach Ganier in the first place: every joy becomes wonder under her attention. Every pain becomes tenderness.

These forces bleed into each other until they are intrinsically linked: Ganier is a child sexual abuse survivor. She is a suicide attempt survivor. And yet, if you ask Ganier how she internalizes her feminist identity, she is a proud Black womxn and a non-codependent caretaker. It is this sense of love and pride winning the war of emotions in her life, as a womxn who has empowered herself despite everything, and now even imparts self-empowerment to other women and young girls, that most distinctly makes Ganier our Featured Feminist of the week.

For Ganier is to younger girls what she needed in an older role model growing up, but ended up having to become for herself. “My mom didn’t believe me [at the time],” Ganier explains calmly regarding her childhood and father’s abuse. “She was a stay-at-home mom [who couldn’t support the family on her own] — maybe she felt she needed him. In my heart, I knew I didn’t want to be like her [then] — to need anyone to feel complete or happy or worthy of good things.” Ganier went on to explain her relationship with her mom is now strong, healthy, and loving — one she is incredibly grateful for.

As she speaks, her composure is smooth as steel. Here we are in my messy apartment, sitting on the couch together, surrounded by film props and costumes, and she sits so poised — grounded and unmasked in a maelstrom of play-pretend things.

“I think my feminist awakening is a result of that experience, being an incest survivor from when I was 3, until I was 15 years old … Because of that experience, I’ve never felt the need to diminish myself in order to make men feel good about themselves … I refused to live my life feeling like I was less than a man. I did not need them to confirm my worth, and I did not need them — nor anyone — to take care of me.”

More importantly, Ganier focuses on supporting other women, and teaching children of their right to set boundaries. “[Because of my childhood,] it’s always been important to me to uplift young girls. For example — I’m a nanny to this nine-year-old girl named Aleema and her brothers, Aura [who’s 11] and Lennox [who’s seven],” she smiles proudly, tellingly crediting her own healing to her years of service to others. “About a month ago, the siblings came with me to walk dogs, and I told them — making especially sure Aleema was paying attention, because girls are so conditioned to be ‘good girls,’” she frowns now, looking straight at me — she leans in, continues lowly: “I said, if you are ever around adults, and you get a funny feeling in your tummy, that is your intuition. That’s your gut telling you that something’s wrong. And don’t you worry about anyone’s feelings. You act on your gut, and if you have to, you scream. The feeling that something is wrong or off is not in your mind. It’s not in your mind,” she assures me so carefully, I’m suddenly not so sure if we’re still talking about the same stakes. Under that intense stare, gripped by its insistence to be remembered, I wondered whom she truly meant those words for — Aleema, put upon with her life walking the dogs? It seemed a little much all of a sudden. Or, more likely, to the reflection of her younger self?

“What I told Aleema, I couldn’t do for myself for years,” Ganier confesses and leans away, as if in answer to my unspoken thought. “No one believed me [while I was growing up], that ‘daddy was doing this to me’ — when I was 15, I tried to kill myself. My doctors never asked about the sexual abuse or even why I would do such a thing — they even made me have group therapy sessions with him.” She’s calm again as she gives the details, even as I struggle simply to take in how real they have suddenly become. “I learned to ask, am I really feeling what I’m feeling? And if so, that my feelings didn’t matter. Until maybe three or four years ago, [because of the] negative messages my ‘dad’ gave me, I hated myself as a whore, as a gay woman …” Ganier doesn’t dwell, quickly moving onto her work with a life coach and her commitment to therapy. However, there is no pretending it’s as easy a path to recovery as she makes it seem.

We take several short breaks during the interview. I plan them for her benefit, but Ganier never actually falters in her openness and wellbeing — so they really end up being for me. As much as I wish to master such serenity for myself, when I have heard so many stories like this from other women close to me who’ve survived sexual assault, it still shakes my composure. And Ganier is the oldest womxn to share her story with me, and the first to show me what surviving sexual assault looks like in the longterm — a sight that humbles yet honestly upsets me to have to imagine in the first place. During one of these breaks, Ganier asks that I not portray her as a victim, and I fiercely promise I won’t do such an injustice. But, it is difficult for me to recount some of the unforgivable details and to feel so hateful about them, and then try to portray her strength as if I really understand it. I wanted to ask, as defeatist as it may have sounded: don’t the details still hurt you anyway?

I am a cynical person. I believe in love, but I tend to think people either ruin what they love, or ruin themselves acting out of love sooner or later. And there is so much love Ganier has to share that I feel has been threatened with ruination at so many turns: as a daughter who had to parent herself, as a Black feminist after slavery and Jim Crow, as a gay womxn whose sexuality has been used to shame her … To see her take control of her narrative and write a better story for herself against all discouragements is life-changing. It is both humbling and empowering to talk with her, to find that it is simply impossible for me to do her strength justice in writing, to even try to comment upon how Ganier has arguably gone through a million kinds of emotions in her life to make the very brave and compelling assertion that above them all, it is always best to choose love.

“I believe you can speak your reality into existence,” Ganier had smiled at me as we walked to my apartment, sunlight beaming over the flowers in her hair. The California wildfires had upset her throat that morning, so she had worn a crown of sunflowers to make herself feel better — it also made her radiant. The quiet confidence of her words had struck me dumb, even more than anything she’d said before or would say later to me during our interview — more than our conversations about her seeing God as the expanding universe, her battle later in life with uterine cancer and infertility, the historical roots of how and why Black women in her family have had to deal with toxic masculinity, repairing her relationship with her mom, the need for Foucaldian protest and her experiences as an activist (or, perhaps and in retrospect, because of those conversations).

“Before I got into UCLA as a transfer student, for example, I would tell people that I’m going to study here! A part of that happening is grades, of course, but a big part was my being excited and talking about it. Your thoughts and actions are more important than you think,” she continues to ramble on, easily and optimistically. As if, in spite of all we go through, discovering the key to life is as simple as believing you can still make things even the tiniest bit better. Perhaps, it is.

“Practicing my feminism is my way of beginning a journey of self-love,” are her last words before I walk her back to campus. “My feminism is my making the choice to love myself. It’s standing up for myself. It’s getting used to not being afraid. It’s speaking my truth and all the work I put into achieving these goals, as well as imparting the fierce importance of the act of self-love and self-acceptance to the girls and women in my life, as issues naturally come up,” she lists — different things that, ultimately, mean the same thing — “It’s my imparting that you’re important,” She gestures to me, finally, and for you. “To the last breath we breathe, we are all important in society.”