The Failed Revolution Club

Photo by Ami Katagiri.

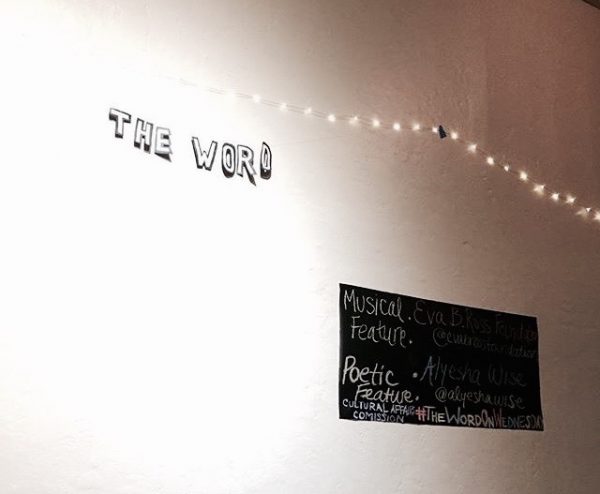

The Word on Wednesdays is not usually a site of hostility. It’s the opposite, actually — every Wednesday from 7-9 p.m, a tight-knit and extraordinarily welcoming community gathers in Kerckhoff Art Gallery to listen to one another’s poetry. This weekly open mic, hosted by the Cultural Affairs Commission, is a space of support and healing and often abundant joy. All who adhere to the rule of mutual respect are welcome, but the Word’s staff and audience are largely comprised of women of color and queer folks. The term “safe space” might be tainted by the scorn of right-wing discourse, but that’s truly what the Word is: a sanctuary for students whose identities and narratives aren’t always respected by the campus at large.

This sense of safety was violated abruptly on Feb. 27 when three members of the Revolution Club infiltrated the Word, creating a loud and abusive spectacle that ended only when campus security forced the men out of the room. The club, a communist organization in the school of Bob Avakian, uses the tactics of protest and disruption to advance its goal of radical Marxist revolution. Apparently, this revolution entails harassing women and nonbinary people of color, desecrating the few spaces where they are allowed to exist in peace.

Midway through the night, a Revolution Club member read a poem about global violence against women. It’s an important topic to be sure, but audience members were uncomfortable with a white American man crudely narrating traumas that he has never experienced. Word staff intervened, and the Revolution Club member launched into a diatribe against intersectionality — a theory coined by Black feminist Kimberle Crenshaw to describe the way oppressions intersect and interact on a variety of vectors, including but not limited to the identities of race, class, gender, and sexuality. The Revolution Club conflates reductive identity politics with intersectionality and faults campus progressives for passively “staying in our lanes.” To the contrary — intersectionality is a tool that has allowed marginalized people to assert their lived experiences as worthy of attention and validation in public discourse. It’s a nonnegotiable requisite for any real and comprehensive liberation.

The debate escalated into an abrasive confrontation. The Revolution Club members were asked to leave, but they refused. The white member shouted that intersectionality is a form of false consciousness, and our fixation on identity divides the masses and prevents us from seeing “content” — which presumably comprises only capitalism and imperialism. That we’re so elated that Barack Obama had a “Black face” that we cannot recognize he is a war criminal. That our country is bombing civilians abroad and we’re “just” reading poetry.

We’ve seen these men before. We meme them as socialist bros in the front row of philosophy lectures who play devil’s advocate while women’s hands get tired from staying raised. They’ve read their Marx but not their Moraga and they probably voted for Jill Stein in Bernie’s name.

But memes are not confined to the virtual, and these men’s eagerness to take space and violate safety causes material harm. If colonization can be defined as a politically opportunistic invasion of a place where one is not welcome, the irony becomes apparent — here is a self-important white man replicating the very dynamics of oppression that he decries in U.S. foreign policy.

And this is why it does matter that the Revolution Club member harassing the Word community was white and male. Only a white man’s worldview could select class and imperialism as the only relevant axes of oppression; only a white man could fail to understand that race, gender, and sexuality are the raw material for our capitalist and militaristic institutions. The man’s conduct demonstrated the toxicity of a framework of revolutionary action defined by men, one that is rooted in yelling and strong-arming and psychologically violent disruption.

It is also a very patriarchal brand of condescension to assume that a room full of politically aware college students cannot differentiate between the neoliberal optics of representation and meaningful systematic change. It is absurd and incorrect to think we can’t distinguish performative wokeness from the radical dismantling of oppressive institutions, or that we cannot tell the difference between overly-deterministic identity politics and the very real ways the vectors of identity structure our society. We know Barack Obama wasn’t the fetishized apex of racial justice (because we understand intersectionality). We grapple with such complexity in our poems, which members of the Revolution Club would have realized had they attended the Word in good faith.*

Word staff member Mando Berumen-Garcia noted that the Word does not intend to suggest the Revolution Club must follow respectable standards for political activism. Instead, the Word community objects to the group’s unprincipled imposition of a political agenda on others, which creates a bad rap for other leftist organizations and alienates potential allies from the goal of an anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist future.

Writers spend a lot of time thinking about how words can change the world. Poets at the Word come from a rich tradition: in “Theory as Liberatory Practice,” bell hooks critiques the idea that naming and discussing lived experience is not a form of revolutionary activism. “I am grateful to the many women and men who dare to create theory from the location of pain and struggle, who courageously expose wounds to give us their experience to teach and guide, as a means to chart new theoretical journeys. Their work is liberatory.”

“Why am I compelled to write?” Gloria Anzaldúa wondered in “Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to Third World Women Writers.” “I write to record what others erase when I speak, to rewrite the stories other have miswritten about me, about you … I have never seen so much power in the ability to move and transform others as from that of the writing of women of color.”

We talk a lot about what the revolution will not be — not funded, not tweeted, and according to the Revolution Club, not intersectional — but we’re better off cultivating a vision of the revolution we do want to see. I think mine looks like queer people of color sharing poetry on Wednesday nights. Many small, beautiful revolutions.

*For the record, Revolution Club members are no longer welcome at the Word in their organizational capacity.