Hey Netflix, Cancelling Good Shows Won’t Make Us Love You

Image source: YouTube.

Netflix canceled “One Day at a Time” after three seasons, and that’s a problem.

“One Day at a Time,” Norman Lear’s reboot of his original series that aired from 1975-84, surrounds the day-to-day lives of a Cuban family. The mother Penelope, played by Justina Machado, is an Afghan war vet and current nurse, who struggles with PTSD after the war. She is the single mother of two, Elena (Isabella Gomez) and Alex (Marcel Ruiz) and daughter of spunky Lydia (Rita Moreno), an immigrant from Cuba whose adoration for her culture can be both extremely heartwarming but can also be a source of frustration for her family.

To simply put in context the imperativeness of “One Day at a Time” (ODAAT), especially with its fun and lighthearted 3-camera sitcom format, I’ll highlight some key issues brought up in only the first episode that speak to broader political discussions

The show pretty much begins with an argument amongst the three generations of women in the house concerning whether Elena will have her quinceañera. To bluntly summarize, both Lydia and Penelope want Elena to have her quinces, particularly Lydia, because of its significance in Cuban and Latinx culture. Elena does not want to have a quinces because to her, celebrating this tradition only perpetuates the misogynistic outlook of viewing a girl as property that is to be auctioned off to potential male suitors once she comes of age. This argument demonstrates the conflict that many young women (very much including myself) growing up in immigrant households face: to follow tradition, which often coincides with being proud of one’s cultural heritage, or branch off for the sake of staying true to one’s feminist values, and attempting to find that happy middle.

While they reach a compromise by actively listening to and understanding the other, through which the show visibly portrays the rich and complex nature of the relationships of women of different generations who grew up in different contexts, the various questions that this conflict raises are fundamental in the lives of many. Would Elena be abandoning her heritage by not doing a conventional, yet arguably essential, practice because it contradicts with her personal morals? Is not wanting to do such a tradition just simply a byproduct of colonization, internalizing the notion of “Western” correctness? By not wanting to do it, is she just being complicit to a system that aggressively feeds the message that a culture that is not Eurocentric is wrong?

This episode also presents situations that delve into issues surrounding the expectations and subsequent repercussions that single mothers face: to keep a strong exterior in the face of adversity, to find a partner because of the wrongly ingrained belief that that is the only method of child-rearing, the problems that single mothers face when this belief turns into a mode of desire, but how it’s also okay to desire love. Penelope toward the end of the episode laments to her mother about how she wants to be held once in a while, to have someone to tell her everything is okay, but that wanting such doesn’t attest to her capabilities as a mother. But at the end of the episode, Lydia walks into Penelope’s bedroom during the night, to cuddle and hold her. Not only does this scene validate Penelope’s desire for affection, but it also displays that love doesn’t only come in romantic form; how love, while nice to have romantically, can be just as nice or even nicer to have from family, especially from a Mom.

And yeah, all that and more, happens in less than 30 minutes of the show. And then Netflix decides to cancel it. Here’s why that and Netflix’s subsequent sloppy apology is problematic.

I’ll be the first one to acknowledge the reality that TV shows get cancelled all the time. It’s a byproduct of the economic establishment in which we are immersed for companies to solely focus on profit margins. But it’s interesting how Netflix couldn’t somehow keep afloat a 3-camera sitcom that possesses a passionate fanbase and is centered around the portrayal of people of color and members of the LGTBQ+ community, when it’s estimated that Netflix will spend around $15 billion in 2019 on the making and maintaining of original content, a jump from about $13 billion in 2018. Netflix really couldn’t have allotted some money, which probably wasn’t a relatively large amount given ODAAT’s format, to this substantial show instead of continuing with their strategy of ‘let’s throw all this stuff at the wall and see what sticks?’ It also does not help when Netflix doesn’t release ratings that their shows receive. How many people watching ODAAT (or any other cancelled show for that matter) would have constituted adequate profit that would’ve satisfied Netflix enough to keep the show going?

But the question remains that while these shows that particularly and accurately represent the stories of groups who do not align with the prioritized narrative of the heteronormative, white, cis, male perspective, were canceled, isn’t their initial production a step toward the right direction? Isn’t it better that we had what little time the show was being made for, than none at all? And yes, sure. Cool. I can agree that simply having the perspectives of the marginalized presented on-screen in a lighthearted yet accurate and compelling way is imperative for these groups’ unfortunate fight for public and political affirmation in a society that attempts to strip away their humanity. But what isn’t acknowledged, and rightfully should be, is that while on-screen diversity may be perceived as increasing at this exceptional rate, it’s actually not and is definitely not indicative of the demographics of the US population.

What’s not okay is the implication of cancelation, especially when that cancelation didn’t really make any sense and especially when Netflix decided to issue a statement regarding their choice to cancel as not-a-choice. The problematic essence of this entire situation comes down to how this faceless corporation tries to pretend that it somehow deserves to be seen as your friend, to pretend that the decisions made were not their own, and to attempt that they actually care.

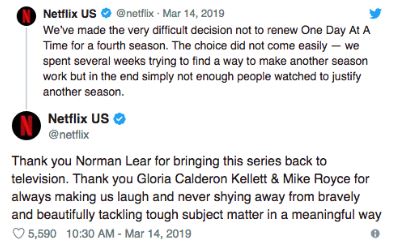

Here’s what Netflix had to say:

[Image description: A series of posts on Twitter from Netflix on March 14, 2019. They read: We’ve made the very difficult decision not to renew One Day At A Time for a fourth season. The choice did not come easily — we spent several weeks trying to find a way to make another season work but in the end simply not enough people watched to justify another season.

Thank you Norman Lear for bringing this series back to television. Thank you Gloria Calderon Kellett & Mike Royce for always making us laugh and never shying away from bravely and beautifully tackling tough subject matter in a meaningful way.

To Justina Machado, Todd Grinnell, Isabella Gomez, Marcel Ruiz, Stephen Tobolowsky, and Rita Moreno: thank you for inviting us into your family. You filled this show with so much heart and warmth and love, it truly felt like home.

And to anyone who felt seen or represented — possibly for the first time — by ODAAT, please don’t take this as an indication your story is not important. The outpouring of love for this show is a firm reminder to us that we must continue finding ways to tell these stories.]

As is represented in the undertones of this statement, Netflix is attempting to come out of this unscathed, to be seen as a victim that had nothing to do this with such a “difficult decision” that “did not come easily.” Netflix wants your sympathy through which it can maintain your subscription. With this statement, they want to divert attention away from the actuality of a mega-corporation making a decision on the basis of financial gain for the sake of presenting themselves as just as disappointed as you; to preserve an idealistic relationship that has recently sprouted between company and consumer where the company attempts to be that friend that’s always there for you no matter what.

Representation of differing marginalized groups has become a marketing tactic for companies such as Netflix. Once the money has been made (or not made), then their seeming concern for diversity, for expressing the stories of these groups in a meaningful way, becomes an afterthought. Many companies that create original content, including Netflix, view on-screen representation as a quota, rather than an ongoing process that requires adjustments and improvements along the way. So Netflix, with this statement, tries to be recognized and receive the brownie points for having made the show at all. They even are acknowledging the present reality that ODAAT garnered an audience that “felt seen or represented—possibly for the first time” because of its showing. They are aware that this show has a positive impact.

They then try to brush aside the implication of cancelation: “don’t take this as an indication your story is not important.” After specifically distinguishing the importance of ODAAT, they try to negate an obvious assumption associated with its cancelation. The mere choice to cease ODAAT’s production, no matter how hard Netflix tries to paint it as not, is inherently placing a value on the show and its contents. This show, to Netflix, was not worth it, so the stories it told, the topics it explored, the groups that were represented, were also not worth it.

Also how interesting is it that Netflix has cancelled shows before, but it’s usually the ones that have casts consisting of people of color and/or tackle issues regarding folks on the margins of public and political discourse that receive statements from Netflix (think “Sense8”)? It is almost like there is a substantial amount of people that will actually care whether the show will get cancelled.

So let’s be real Netflix, you don’t care about inclusivity and representation in your content unless they provide a significant long-term financial incentive, you don’t care about the people who may have felt “seen” or heard through your content, so stop releasing statements pretending that you do. Do better.