The Case Against Voting

I am not the only one to feel disillusioned by the electoral process following Tuesday’s acrimonious democratic debate. But while people around the country are more frustrated than ever by the current state of electoral politics, the dominant message is still that everyone should vote in order to create change.

Until recently, I believed this too. The pervasive argument is that, even if you do not approve of either candidate, it is still essential to vote for whoever’s policies you prefer. However, this rhetoric of harm reduction implores people to participate in “lesser of two evil”-ism; and, focusing on how things could be much worse effectively decenters how things could be much better. Harm reduction has the implicit power to defang and demobilize movements.

Regardless of your decision, it is essential to understand the reasons many choose to abstain from voting in order to appreciate the contradictions our ‘democratic’ system holds for marginalized groups. While people choose not to vote for many different reasons, this article will be specifically focusing on the arguments common among marginalized groups.

In the midst of the midterm elections two years ago, FEM’s current editor-in-chief Chiamaka Nwadike wrote an article that discussed many of the reasons people choose not to vote. One of the primary arguments against voting is that “the United States government is an illegitimate system developed on stolen land and exploited labor.” As such, voting is unproductive for movements based in dismantling the state rather than reforming it. Nwadike also references the history of voting rights in the United States and disenfranchisement of minorities that continues to this day.

For many people, the act of voting cannot be separated from its exclusive origins and repressive history. When the United States gained independence in 1776, only land owning white men over the age of 21 could vote. In 1868, voting rights were extended to all men with the passage of the 14th amendment, and finally to women with the adoption of the 19th amendment in 1920. Looking at a timeline of amendments, however, masks important details about the ways in which this legislation was created and enforced.

The suffrage movement betrayed Black people, particularly Black women. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, one of its most influential figures, believed that women would be “degraded” if Black men got the right to vote before them and fought against the passage of the 14th amendment. Black activists were routinely excluded from the white woman’s suffrage movement of the early 20th century by organizers like Stanton, who embraced white supremacy for political capital.

Indeed, working white women and women of color remained marginalized by and suspicious of the mainstream suffrage movement led by Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. According to Angela Davis, “it was probably because of the [bourgeois] ideology’s blinding powers that [Susan B. Anthony] failed to realize that working-class women and Black women alike were fundamentally linked to their men by the class exploitation and racist oppression which did not discriminate between the sexes.”

While the 19th amendment enfranchised white women, it failed to provide material gains to Black women who were still blocked from voting in many places by measures like poll taxes and literacy tests. These practices were outlawed by the 1965 Voting Rights Act, but things like registration deadlines, blocking people with felony records from voting, and voter purges persist, and disproportionately affect marginalized groups.

Given the history of voting rights in the United States, it is unsurprising that so many marginalized people remain pessimistic about the ability of voting to enact real change, and the commitment of most government officials to their well-being. This history is still woven into the question of whether or not to vote for many people in this country.

“I’ve spoken out many times over the years about the dangers that electoral politics hold for mass movements- reducing involvement to this one moment, this one person, and making it unclear to masses of people that power under capitalism comes at the point of exploitation,” reads a Feb. 18 tweet from American creative Boots Riley. Riley views elected officials as beholden to the interests of elites and generally unwilling or unable to undo structures of oppression. As a result of this belief, Riley has never voted before, but plans to vote for Bernie Sanders in the upcoming primary. However, his reasoning is based less on the candidate himself than on the candidate’s supporters.

I have never voted for a candidate in my life.

— Boots Riley (@BootsRiley) February 19, 2020

But I will be voting for Bernie Sanders in the democratic primary and the general election. If I’m doing that, there are probably tens of millions in that same position.

Let me explain why I’m doing this now:

“What I am endorsing is the movement that has grown around him that involves millions of people who are willing to consciously and openly engage in class struggle in order to make these reforms happen,” Riley added in the same Twitter thread. This reason for voting abstention, as well as his decision to vote for Sanders, relates to the previously discussed ideas of voting as a system organized by the elites and invested in maintaining the status quo.

Riley’s belief in the importance of radical organizing is similar to that espoused by Nwadike in her 2018 article, which argues that contemporary voting by progressives is often a “savior complex” which absolves guilt without creating institutional change. “Just voting will not rid us of white supremacy. We cannot vote away capitalism. Doing the work that needs to be done for true liberation is beyond the scope of voting every four to eight years,” argues Nwadike.

Another reason for not voting is that it will only continue the American imperialist project, even by the most progressive candidates. An article by activist Joshua Briond argues that any welfare state envisioned by democratic socialists in the Global North is necessarily sustained by colonial legacies and imperial violence. Furthermore, American foreign policy will always cater to the interests of elites, which are in direct opposition to the well-being of marginalized people around the world.

“Regardless of who you’re voting for in the 2020 presidential election, your vote will inevitably be casted for the next global terrorist-in-chief. The next president—whether domestically “progressive” or not—like all presidents, both past and present, is going to cast racialized terror on oppressed and colonized people everywhere,” says Briond.

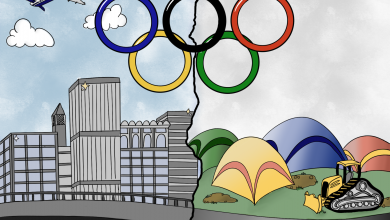

The voting system in the United States was designed with rich white men in mind, both as participants and beneficiaries. As voting has become more inclusive, the system still works to protect the elite and oppress already-marginalized groups. The history of voting must be considered when analyzing its present form as a method of upholding the status quo which, in America, is violently oppressive. While voting can create real change, electoral politics fail many people, and their choices not to vote are valid. They should not be forced to participate in a system that oppresses them.

The common depiction of non-voters as lazy, uninterested, apathetic, under-educated or cynical is reductionist. These characterizations are weaponized by the establishment to discount the very legitimate work of activists and organizers, especially Black radicals. By painting investment in electoral politics as necessary for change, we ensure the continuation of an electoral system that benefits the elites. While elected officials can and do fight for progressive change, this does not undo the exploitation of marginalized people by the ruling classes that forms the basis of the settler economy.

This is not a cynical article. I’m not looking to say that U.S. democracy is futile, or that no one should vote. Rather, my purpose is to understand the complexity of voting for marginalized peoples and recognize the power of organizing that intentionally disavows an institution of our own oppression.