The Los Angeles Worm Farm Collective: Building for a Better World

My original intention with this piece was simply to highlight the work of a queer and trans people of color (QTPOC) cooperatively owned and operated urban worm farm. Upon interviewing and learning about Los Angeles Worm Farm Collective (LAWFC), I found out just how exciting this project is when viewed within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, this article contains two parts: the first half explains the foundations of LAWFC and the second details how they’ve been able to put their principles and work into practice to build power in their communities. I hope this piece can inspire marginalized workers, farmers, and community members to build the kind of world they want to live in that is mutually vulnerable, open and compassionate.

After feeling demoralized from the exploitative work environments and hierarchical structures of their nonprofit social service jobs, the LAWFC founders decided to start a co-op with horizontal governance. Steph Van, lecturer at Cal State L.A. School of Social Work and one of the founding worker-owners, explained that all the original founders were part of a community organizing group called Equal Action, which mobilized and provided space for queer and trans youth of color. LAWFC began as a means of starting a business in the alternative economies movement and is rooted in its inherent cooperative structure which seeks to liberate workers from oppressive models.

The Los Angeles Worm Farm is an urban farm currently based in Echo Park. I visited Keshy Jeong, an L.A. and Bay area-raised art student and one of the worker-owners of the farm (worker-owner is a singular title denoting both worker and owner). As we strolled through Echo Park, energized by the bustling park full of food and jewelry vendors and families enjoying the small plot of nature, Keshy and I discussed what they were building with LAWFC. “For me, it’s really important that the farm stays in this metropolitan city and is metro-accessible,” explained Keshy. Having a farm in the city allows the worker-owners, many of whom have lived in Los Angeles since childhood, to integrate their farming practices into their everyday lives as 1st and 2nd generation immigrants in Los Angeles.

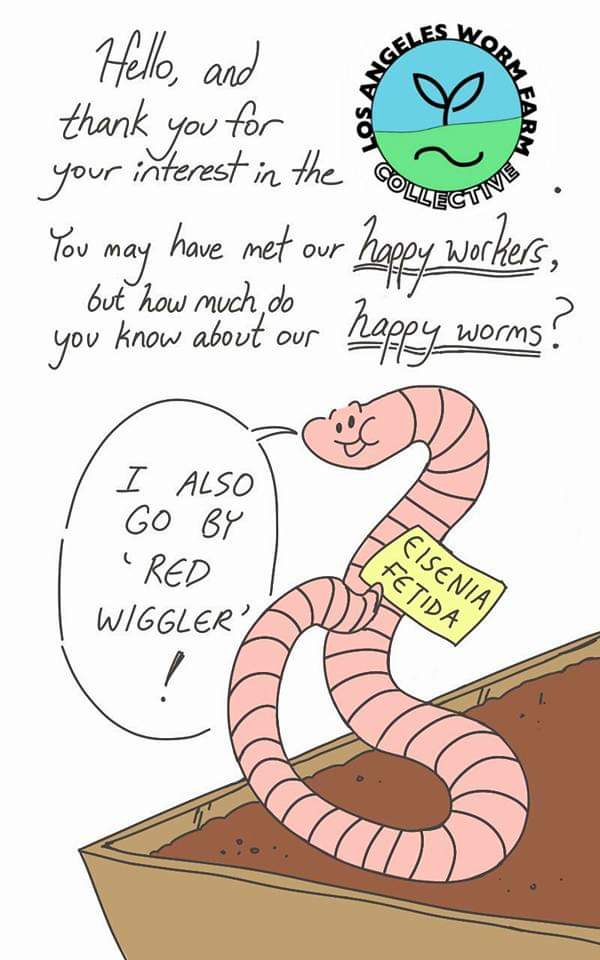

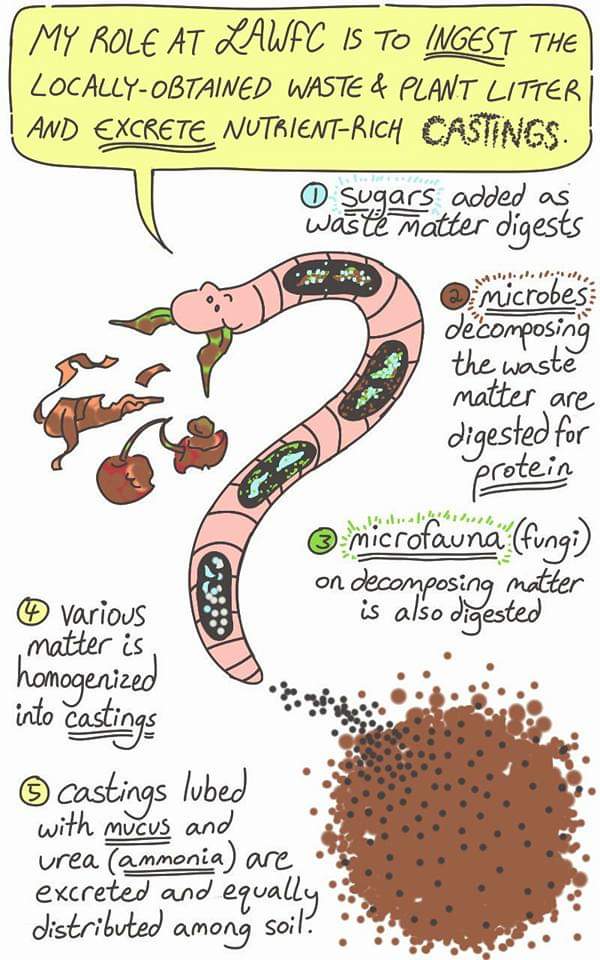

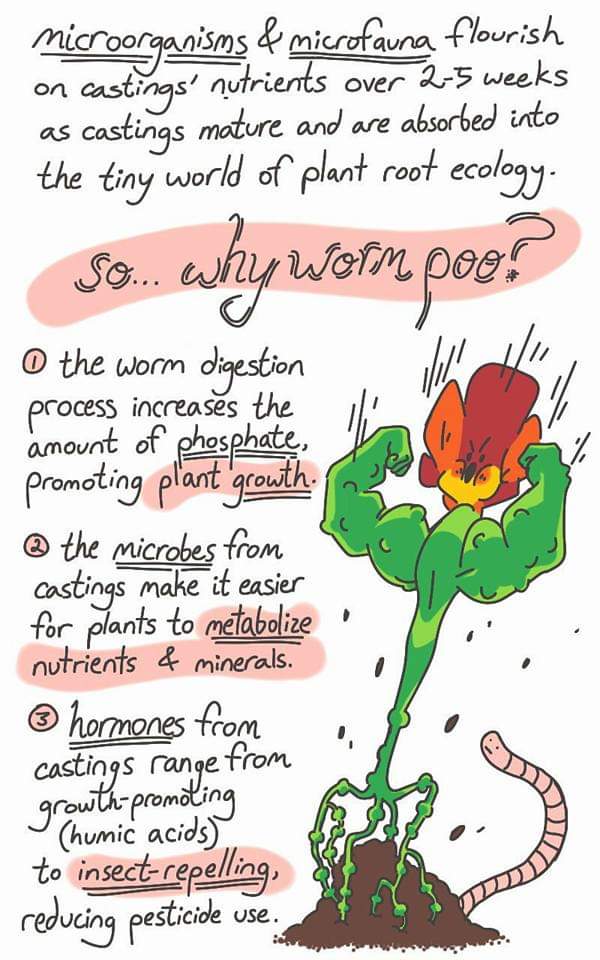

By composting with earthworms, LAWFC converts L.A.’s nutrient-poor soil and food waste into fertilizer for locals to use in their neighborhood gardens. Worm castings are organic fertilizers and soil conditioners. Worms ingest locally obtained food scraps and cardboard and excrete waste that is nutrient-rich and conducive to plant growth. The naturally occurring hormones within the castings also have insect-repelling properties, reducing the reliance on pesticides.

The land used to compost and cultivate worm castings was donated by Seeds of Hope, a food justice ministry of the Episcopal church communities of L.A. with a decades-long history of providing space and refuge to farmworkers’ alliances and migrant refugees. Although the land is entrusted to them by Seeds of Hope, LAWFC functions autonomously with their work guided by 5 co-owners.

Keshy cited 19th century recently emancipated Black American workers and peasants as the inspiration for the cooperative business model. The failure of the reconstruction era and the unchecked practice of debt-induced, coerced labor radicalized many of these workers to ditch the wage system in favor of economic sovereignty. Following the abolition of slavery, transracial coalitions of labor organized to abolish the wage system by jumpstarting cooperatives and strengthening unions. One of the missions of LAWFC is to spread the knowledge on setting up and running a cooperative business. They hope to inspire and aid others interested in alternative models of work.

Outside of LAWFC and being a student, Keshy has multiple jobs such as archival work in their campus library, occasional speaking gigs as an organizer, transcription work for documentary films, and translation services for Korean and English. As an individual who’s done a variety of part time jobs, studied at multiple colleges,and been involved with various grassroots organizations as well as non-profits, Keshy learned the hard way about exploitation and burnout in academia, wage jobs, and in movement spaces. “I’m all about setting boundaries,” Keshy proudly affirmed. “LAWFC has taught me that the individual’s capacity should define the project rather than stretching people’s capacities to meet a project goal. No matter how passionate you are about getting a certain project done, it’s not worth losing sleep over.”

The governance and structure of LAWFC is adapted from sociocracy, a non-hierarchical organizational model wherein each worker-owner takes lead in different domains (such as farm operations, sales, media, administration, etc.) that the rest assist with. LAWFC also draws from other co-ops in the alternative economies movement like Anti-Oppression Resource and Training Alliance (AORTA). AORTA shared their equitable pay scale system with LAWFC to adapt for themselves. The equitable pay scale system considers workers’ disparate needs, recognizing that low-income renters and caretakers are more reliant on the collective’s revenue.

Among all the worker-owners, there emerged a consensus that although the profits generated from the worm farm is not a primary source of income for any of the farmers, the workspace does meaningfully transform their relationship to work. In all about love, bell hooks described an intangible feeling of fulfillment when a “love ethic” is incorporated into one’s work. Working in an oppressive environment has debilitating effects on workers’ self-esteem. Incorporating a love ethic into a workplace would mean not only loving the work one does, but also loving the people one works with. It would mean not being constantly forced to prove one’s worth for an employer. Worker-owner Steph Van mused that the worm farmers have become ill-equipped to tolerate oppressive working environments, and that every worker should feel empowered to realize their value beyond oppressive work environments.

For many of the worker-owners, the collective is also an opportunity to work with other queer and trans diasporic Asians. Some have family histories rooted in rural areas of Asia while others simply grew up watching their parents and grandparents garden as a means of stress relief. For instance, Keshy’s family is from rural South Jeolla in Korea, where workers and peasants resisted the South Korean dictatorship in the 1980 Gwangju Massacre and Uprising. There exists an aspect of gardening that is an act of remembering and a return to process for those with peasantry roots. As members of the diaspora, we are disconnected from our heritage culture in a thousand different ways. American convenience and its supermarket corporations on stolen land expedites this disconnection. Convenience robs us of the process that is involved in the creation and reproduction of cultural practices. Being able to have a space wherein queer and trans diasporic Asians have the safety and trust of working with others and can grow heritage foods is invaluable.

But LAWFC is not just a safe space. It is a site of convergence for those principally aligned with ideas of wealth redistribution and revolution. Bringing revolutionary organizers together in a functioning business that is centered around cultivating food sovereignty is a way of building power in the anticipation of capitalist crisis. And in the span of writing this feature, the global pandemic which is straining all levels of economy has called the LAWFC to action. The UCLA Anderson School of Management has reported that the next recession is coming early due to the pandemic. News outlets have been throwing around the word “unprecedented” to describe the situation. The injustices of prisons, immigrant detention camps, homelessness, food insecurity, the U.S. healthcare system, neoliberal productivity models, and the devaluing of essential workers has brought more people into recognizing the deformities of capitalism. As capitalism continues to entrench itself deeper into its own contradictions, LAWFC has been uniquely positioned to succeed and lead.

The farm collective experienced a spike in orders since the pandemic reached the U.S., doubling their supply of worms within a matter of weeks. People have been reminded of their ability to grow foods with the growing mistrust of dominant food systems and concerns of food shortages (although the problem is a matter of distribution, not scarcity). Thus, LAWFC has been thrust into action to meet the demands of those seeking to build food sovereignty. In doing so, they are jointly able to spread their business model and inspire others to jumpstart worm farms and co-ops of their own. We are recognizing that consumer capitalism has disconnected us from so many practices essential to survival. As whispers of dystopian apocalypse become louder, hard skills like gardening grow more and more attractive.

The LAWFC has also had direct involvement in aiding the efforts of Reclaiming Our Homes. Reclaiming Our Homes is a movement based in East L.A. inspired by moms4housing, a movement of unhoused mothers who successfully took over vacant homes in gentrified Oakland. Reclaiming Our Homes has been taking over vacant homes owned by the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans). Caltrans bought up property and displaced hundreds of residents in order to build a freeway that never got built after wealthier residents blocked its development from crossing into their neighborhoods. Now, over 100 homes owned by the state sit vacant while 60,000 Los Angelenos live on the streets. Since there is no way for unhoused people to stay home during the pandemic, volunteers and organizers have been helping families move into these homes and defend against police activity. LAWFC has committed to donating up to 25 gallons of worm castings to the families taking over homes as each reclaimed home is expected to have their own garden.

The work of the collective reaches far beyond their involvement in the worm farm. Keshy, for instance, has been organizing mutual aid networks and jumpstarting crops in 3 community gardens which are within walking distance from their apartment. Since Keshy has also been collaborating on art projects with other students currently incarcerated in Lancaster prison, Keshy has been able to maintain communication with the incarcerated students about their needs inside the prison as well as help them draft requests for hygiene supplies.

By building alternative ways of being in response to the inherent crisis of capitalism, LAWFC has responded to the pandemic in thoughtful and productive ways which aid the most vulnerable in their struggle for justice. The collective of 5 worker-owner-farmers has felt their actions leading up to the pandemic have allowed them to respond rather than react, moving as a fluid organism (worm?) during a time when so many institutions are falling into haphazard crisis and individuals find they have no one to rely on but themselves. LAWFC has been able to brave new tensions because they’ve rooted their practices in something local, tangible, highly organized, QTPOC and disability-centered, and with a commitment to its communities and the principles of wealth redistribution and revolution. To learn more about LAWFC or to buy worm castings, go to https://lawormfarmcollective.com/ or follow them on facebook, instagram, or twitter.