Property, Personhood, and Police: Surveillance and Housing in Los Angeles and Beyond

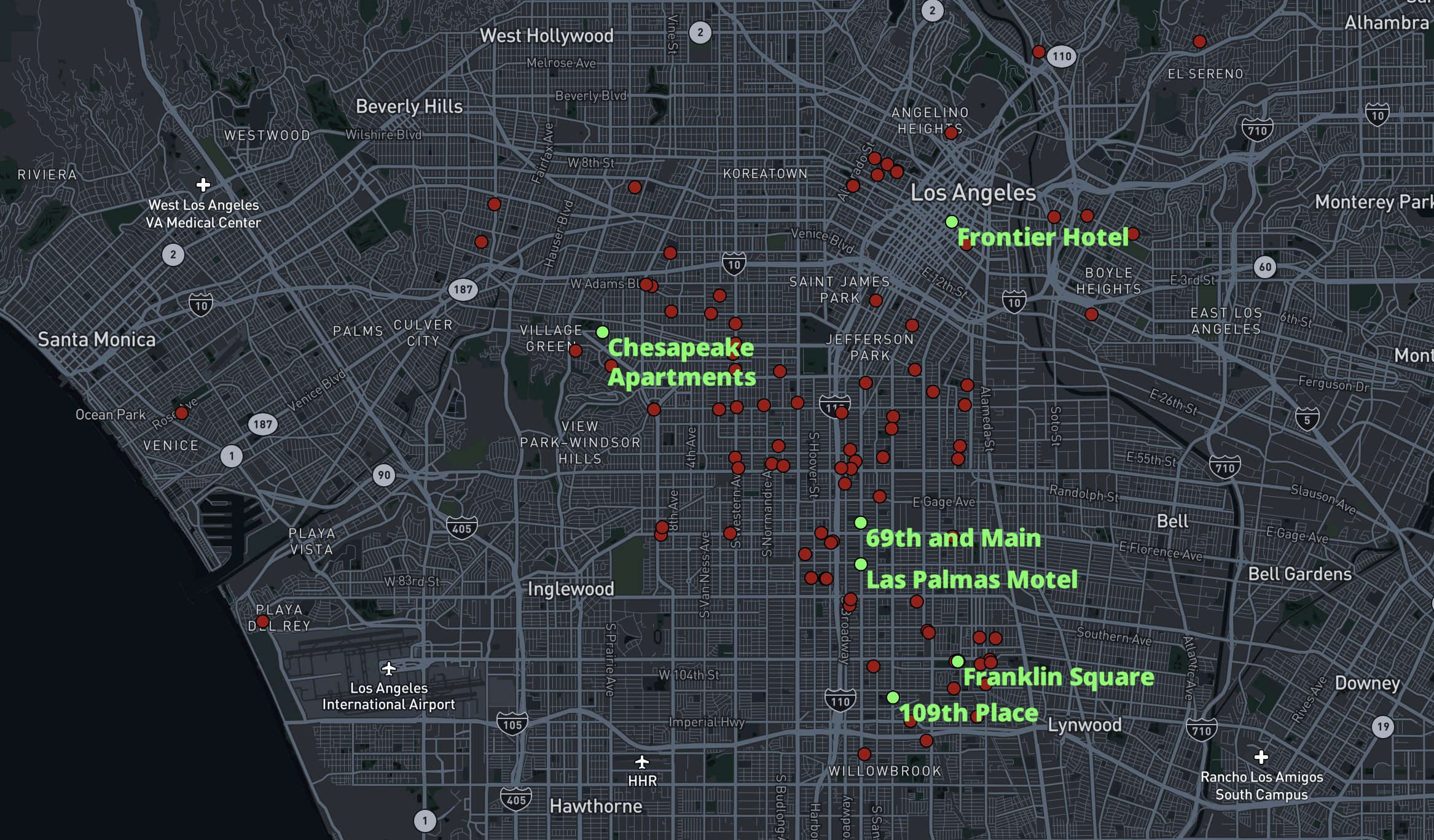

Image Description: This image from the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project website is a map of Los Angeles City in gray. The map contains over 100 small red dots across the city, and they are largely concentrated in the central and southeast regions of the city. There are six bright green dots labeled with the names of the buildings they represent: “Chesapeake Apartments,” “Frontier Hotel,” “69th and Main,” “Los Palmas Hotel,” “Franklin Square,” and “109th Place.” The properties in green are also in the central and southeast regions of the city.

“If they’re going to try and evict us, I’m not going to make it easy. I’m not going to just fold up and go, I’m going to fight.” These are the words of Zerita Jones, a tenants’ rights activist and lifelong resident of the South Central Los Angeles area who faced the threat of unjust eviction.

Her building, along with those of 1,500 other tenants in the area, is under the Nuisance Abatement Act (NAA), a California bill authorizing a city or county government to collect fines for “specified violations related to the nuisance abatement.” Although advocates for nuisance abatement legislation claim it will address safety concerns in “dangerous” neighborhoods to improve residents’ quality of life, in practice, it leads to over-policing in predominantly Black and Latinx communities and perpetuates the stereotype that these groups are a “nuisance.” The tenants were not notified of this filing by the city of Los Angeles and only discovered it when NBC showed up on their doorsteps to do a story about their buildings. In response to this filing and NBC’s story (which turned out to be a misleading representation of the situation), Jones and other residents formed a tenants’ association. With great effort, they were able to intervene in a court case related to this filing. Jones recounted, “In five days we did it, we filled the courtroom with the tenants. […] And the judge felt as though if we were the ones paying rent, we had a say. […] So he granted us the right to intervene.”

Unlike Jones, many tenants do not have the capacity to fight for their right to comfortably and safely exist, which leads to continual fines and even eviction on the basis of what the police categorize as “nuisance.”

On Tuesday Nov. 9, 2021, the UCLA Luskin Institute on Inequality and Democracy hosted a virtual event entitled “Property, Personhood, and Police: Counter-mapping from Louisville to Los Angeles” that addressed the issue of so-called “nuisance.” Four featured speakers discussed their research on the intersection of police surveillance, housing, gentrification, and violence. Although Jones was not present at this event, a recording of her words set the tone for a powerful discussion of these issues.

The first two speakers were Terra Graziani, a researcher and tenants’ rights advocate who founded the Los Angeles chapter of the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, and Pamela Stephens, a doctoral student and researcher in the UCLA department of Urban Planning. They discussed their work for the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project.

The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project documents records of 121 Los Angeles Citywide Nuisance Abatement Program (CNAP) cases from between 2003 and 2018. According to the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project website, CNAP “allows the City Attorney to sue the owners of ‘nuisance’ buildings and mandate owners to install surveillance, evict tenants, or even shut down the property. The program binds together housing and policing, often in service of redevelopment and gentrification.” Although these cases led to a range of outcomes for tenants, they largely relied on the same abatement strategies that infringed on the lives of tenants. The website details six CNAP cases that the researchers felt represented the larger trends across LA.

When it comes to police surveillance in LA, it is important to first discuss the Los Angeles Citywide Nuisance Abatement Program (CNAP). According to the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project website, CNAP “allows the City Attorney to sue the owners of ‘nuisance’ buildings and mandate owners to install surveillance, evict tenants, or even shut down the property. The program binds together housing and policing, often in service of redevelopment and gentrification.”

Rocky Delgadillo, the city attorney and supervisor of the program between 2001–2009, is largely responsible for the current prevalence of CNAP. He currently works as a real-estate sector lawyer, where he advises clients to invest in neighborhoods with “good bones” that were formerly “controlled by gangs.” In other words, CNAP acts as an agent of gentrification — as Graziani pointed out, CNAP intervention usually leads to sale and redevelopment of property to turn developments into more profitable ones.

CNAP is born out of community policing initiatives and targets Black and Latinx low-income communities. Long-term surveillance criminalizes people of color and leads to increasing rates of arrests within these communities. As Stephens pointed out, this process ultimately reorganizes property relationships to maintain racial residential segregation.

CNAP also makes tenants’ lives harder in affected areas on a daily basis. In addition to the ongoing sense of unease created by constant police surveillance, some properties even require the presence of private security guards who are often armed. In other cases, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) recruits neighbors to police each other by putting up “wanted” posters of certain residents. CNAP and LAPD work together to break down the sense of security that all people have the right to feel in their homes and communities. Through this process, Black and Brown tenants are violently forced out of their long-term homes in order to support the profits of big development companies.

The second set of speakers included Jessica Bellamy, a co-principal investigator at the Root Cause Research Center with a background in community organizing, and Josh Poe, another co-principal investigator at the Root Cause Research Center as well as an urban planner, tenant organizer, and geographer. Their work resides in Louisville, another city where Black and Brown tenants are subject to intrusive and violent police surveillance.

It is especially important to push back against the policing tactics of the Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD), because they are responsible for the murder of Breonna Taylor, who was shot eight times by police officers in her home on March 13, 2020. The LMPD operates under a “Place-Based Policing” strategy, under which, as Poe explained, residents who live close to crime are also partially responsible for it, even if they are unaware of it.

Bellamy explained that cities find so-called “comfort zones,” areas where Black people are living in peace and minding their own business, to be dangerous. Although this dialogue takes place under the guise of community safety, the only threat these areas actually pose are to cities’ development goals. Breonna Taylor’s home was considered a comfort zone — although she was not a criminal herself, the police viewed her as a “criminal facilitator” because she occasionally welcomed into her home and received packages for a person suspected of a crime. This led to intense surveillance of her home and eventually her murder.

“Criminal” or not, no person should lose their life to unnecessary and irresponsible police tactics. This is why it is important to push back against police surveillance, which threatens the livelihoods of so many vulnerable community members. The issue of police surveillance and eviction is especially hard to address because cities often overlook the impacts of their actions on tenants. Because tenants do not own property, they are viewed as having “no skin in the game.” Additionally, Graziani pointed out that when dealing with “the lawlessness of the law” in housing, tenants bear the bulk of the burden legally.

Even so, many tenants are organizing to help each other codify their rights in contracts with their landlords. Other activists also advocate to defund the police, which is essential to getting the public funding necessary for social housing. Though police surveillance efforts are stacked against tenants’ rights to live comfortably, community activists like Jones remain a force to be reckoned with.

One way UCLA students can get involved in the fight against police surveillance is through the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition — if you are interested and able, visit their website to donate or volunteer today!