Being Lolita – FEMoir Series

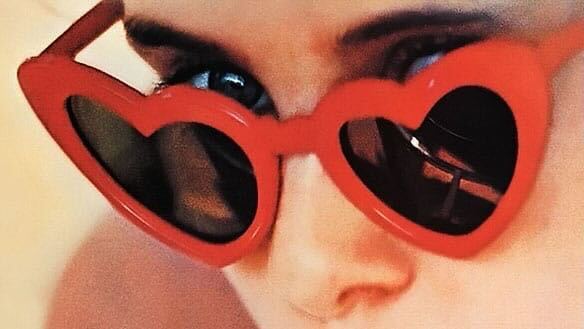

Image description: a grainy and warm filtered close up photograph of a feminine presenting face wearing large red heart shaped sunglasses

Image credits: Snapshot from Kubrick’s “Lolita” (1962 film)

CW / abuse, grooming

It’s frightening when your perception clashes with reality in a sharp, electric flash of clarity and anxiety. You’re terrified that things will be different; that things will be far from the familiar.

I was familiar with discomfort, and pain. I knew what survival felt like and that felt like living. I know I was deeply loved in ways the people around me were capable of. I didn’t know that wasn’t enough – that surviving didn’t mean I was living. I didn’t know I deserved better, needed better.

“My teacher, my knight in shining armor, my secret admirer. Mr. North. Nick.”

Alisson Wood’s memoir “Being Lolita” documents her abusive relationship with her teacher, her knight in shining armor, her secret admirer. It began with Mr. North — the new English teacher at her high school who adored her writing — then Nick — the 28-year-old, “Lolita”-obsessed adult, enamored by the innocence of an adolescent wrapped in pain and sorrow. He became the man who controlled her every movement.

Nick gifted her “Lolita” in the beginning of their relationship. He had inscribed a note within the book: “To Alisson. This book is lust, yearning, and occupational hazards. And lightning. Enjoy.” “Lolita” is a novel about Humbert Humbert who obsesses over 12-year-old Dolores Haze. After becoming her step-father, he kidnaps Dolores and sexually abuses her. Nick instructed Alisson to see Dolores from Humbert’s perspective – as a seductive, promiscuous young girl. Wood grew to envy how Lolita wielded her sensuality and youth, hoping to find this power in her own body as Nick continued to pursue her. It would be a long, arduous journey to understand what was wrong with this dynamic – how “Lolita,” and herself, were actually young girls violated by older men.

Wood existed as far as Nick allowed. Most things she wrote had to be written to him. She went to the school he wanted her to go to, wrote how he wanted her to write, and acted how he wanted her to act. The summer after her graduation, when Wood was overjoyed that they’d officially be a couple, Nick had told her to stop writing entirely so as to not document their affair. No one could know – and no one did during the time of their entire arrangement.

Abusers find their power within their ability to pull and manipulate the strings of your reality into what they need. It’s hard to admit how his words seeped into my mind and warped my perception. I was so distracted by what he wanted from me that I never stopped to consider what I wanted. “Being Lolita” softly revealed what parts of myself had been neglected.

It wasn’t until Wood took a literature class in college that her understanding of their relationship radically changed. Her professor — notably a woman — utilized “Lolita” to illustrate the concept of an unreliable narrator. Wood wrote, “I remember the moment my professor referred to Humbert Humbert as an ‘unreliable narrator.’ The phrase rang through my mind. [I] felt my spine straighten and something invisible creep down my neck.” The pieces of this complicated puzzle had begun to connect in one sharp, electric flash.

Wood’ story was raw and vulnerable. She carefully illustrated how many victims of abuse are drawn into these relationships and are momentarily blinded to the way out. It’s no easy feat to articulate the process of being wrapped in an abusive situation. I’ve stumbled over my own words in explaining how much he hurt me and why I stayed for so long. Behind the tight handiwork of his, I felt loved.

There was something that pulled me towards him before we were even together. We spent hours under the stars, fed each other brownie batter, laughed until our stomachs cramped, and played video games side by side in a world that we built for us. I thought all the hurtful words, gaslighting, and accusations were warranted. It wasn’t him, it was me that needed to be better. Or simply I was being too sensitive, and my shrinking body was a product of my own behaviors. He was trying his best.

Similarly, Wood had to grapple with the two-sided nature of Nick. The Nick who wrote songs on his guitar and named the constellations, and the Nick who threw glass cups which shattered behind her head. She wrote, “I wanted to believe that Nick’s pattern of manipulating and misleading me, of making me feel small and stupid – were unconscious, an accident.” Her words shot through my calloused skin and echoed between the nerves of my body – I wasn’t alone. When your abuser is someone you love, your brain works tirelessly to rationalize their hurtful behavior. Love shouldn’t mean pain, but when it does – over and over again – you have to reconcile their behavior with their words. They yell, scream, and hurt you, but it’s either your fault, or the mistakes of an imperfect human being that says, “I love you. I’m sorry. I won’t do it again.” Over and over again.

It is often that abuse can flower in one’s immaturity and insecurities. Wood wrote pointedly, “At seventeen, I was deeply insecure and convinced I was not capable of being loved.” In high school, she had felt disconnected from her peers. She had come out of psychiatric help at the beginning of her senior year and rumors of her mental condition quickly spread. It was then that she met Mr. North who was told of her struggles and agreed to tutor her in creative writing – a talent of hers that was well-noted by her guidance counselor.

“All I wanted was to be seen. To be acknowledged, to be understood.” Wood had revealed to Nick the weight of her depression, mood disorders, and insomnia that had caused her to leave the school previously. Nick put a hand to her knee. In the safety of his classroom, Alisson felt the warmth of being seen, of being heard. Years later, she realized the moment wasn’t an exchange of respect and compassion, but rather where Nick found an opportunity in the midst of her pain – like Humbert becoming so enthralled with the fragility of a young girl’s mind.

There were many times I had to take a break from Wood’s writings. There were too many parallels with experiences I’ve gone through. She made me feel seen, but at the cost of seeing it myself. It can be a heavy read for anyone, but especially for those who’ve also gotten caught in the cycle of abuse. Past wounds feel fresh once you realize there is much more to your story. Finding more pain to unravel is not particularly pleasant, but Wood doesn’t leave you alone. She assures the reader that the abuse you endured could never be your fault, and that healing is more than possible. There’s power and autonomy to be regained in your mind and body.

At the end of the book, Wood illustrated the beginning of her adulthood as a literature professor. She conducted courses in which she led her students, many of them young women, through analysis of the same book that held her painful history: “Lolita.” As she listened to her students offer critical and insightful examinations of the book – ones she notably wished she had been equipped with – Wood found light in what had been darkness for much of her childhood. If you’ve struggled to make sense of your own experiences, I highly recommend reading her story.

Wood wrote, “In the rabbit hole of the relationship, I couldn’t understand how I got here or what was wrong with this love story.” Her relationship had been a whirlwind of affection, infatuation, and pain. In the midst of such chaos, you’re left wondering what had gone wrong when everything had felt so right in the beginning. Nonetheless, the veil dropped and Wood saw Nick for what he was – an abuser, a manipulator, a narcissist in his own world. It took time, but she made a life for herself far from it. And as I turned the last page, I felt empowered – there is more than enough time for me too.