Misty Copeland: Breaking Through Ballet’s Racial Boundaries

“I know I will also dance for those who aren’t here, who have never seen a ballet, who pass the Metropolitan Opera House but cannot imagine what goes on inside. They may be poor, like I have been; insecure, like I have been; misunderstood, like I have been. I will be dancing for them, too. Especially for them. This is for the little brown girls.”

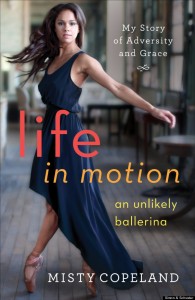

Misty Copeland has worked with Alexei Ratmansky, currently one of the most popular ballet choreographers, gone on tour with Prince, and written a memoir, Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina. Unlikely is a fitting description. Unlike the typical ballerina, Misty is short, curvy, and black.

Copeland grew up in Southern California and when she first started ballet at thirteen, it was in a class sponsored by her local Boys and Girls Club. At the time, she lived in a house with her mother, siblings, and stepfather. Later, she lived in a motel room, sleeping on the floor with her brothers and sisters.

Copeland grew up in Southern California and when she first started ballet at thirteen, it was in a class sponsored by her local Boys and Girls Club. At the time, she lived in a house with her mother, siblings, and stepfather. Later, she lived in a motel room, sleeping on the floor with her brothers and sisters.

Dance, she says in her memoir, was a refuge from the difficulties in her life.

With a scholarship from her teacher Cindy Bradley, in a few months she was en pointe, an essential part of ballet where the dancer puts her entire weight on the tips of her toes.

For comparison, most ballet dancers start classes when they’re small children, and spend years training until their teachers decide if they’re ready to go en pointe or not. Eventually, she moved out of her home to live with Cindy Bradley and continue her dance lessons.

After a few years, which included a summer program with San Francisco Ballet, a highly publicized custody case involving her mother and ballet teachers, and two summer intensives with American Ballet Theatre (ABT), Misty joined ABT’s Studio Company, and then ABT proper.

At the time, she had the ideal ballet body — small head, long neck, slim build, and big feet. But once she began menstruating, Misty faced a new challenge of having a curvy body.

In her memoir, she speaks about how difficult it was to fit into company tutus, and to find a bra that would both fit and allow her to move freely. In her memoir, Copeland wrote:

“Finally, the ABT staff called in me to tell me that I needed to lose weight, though those were not the words they used… the more polite word, ubiquitous in ballet, was lengthening. ‘You need to lengthen, Misty,’ a staffer said. ‘Just a little, so that you don’t lose your classical line.’”

As comments came from all sorts of people, Misty turned to emotional overeating, but was eventually able to stop that habit and learn to both accept her body and support it, nutritionally.

Then things became even more difficult.

Since she joined ABT, Misty Copeland has been the only African-American woman in the company.

While sheltered from racist comments as a child, during her time in the corps de ballet, Misty was faced with people saying that she couldn’t fit into a ballet like Swan Lake and with jokes about how she used makeup to make herself appear lighter.

She was put primarily in contemporary works, rather than the classical ballets that she was trained to do. After speaking to the artistic director of American Ballet Theatre, Kevin McKenzie, Misty began to dance in more classical story ballets.

Now, she is the first African-American soloist in thirty years.

She takes that role very seriously, seeing it as a position through which she can tackle the lack of diversity in ballet. She is spokesperson for Project Plié, a partnership between American Ballet Theatre and the Boys and Girls Club of America to give scholarships to young dancers of color.

She spoke at TEDx Georgetown on ballet’s power and lack of diversity. She created the title role in Alexei Ratmansky’s “Firebird,” and then released her memoir last month.

Her memoir is one of several that talks about the intricacies and problems within ballet, but it’s unique in that it addresses the issue of accessibility.

She writes clearly, and she explains ballet terminology with simple words, without “dumbing down” for people who aren’t interested in ballet. Her writing style doesn’t diminish her accomplishments, and while some critics thought her memoir was unnecessarily arrogant, Misty has a lot to be proud of.

In the ballet world, Misty Copeland stands out not only because she is a black dancer in a predominantly white art form, but also because she refuses to be silent about it.

She works to inspire young dancers of color to continue on in an art form where many of them are told that they won’t get leading roles because they are black, and she also addresses the systemic problem of low income among people of color that makes ballet such a difficult art form to break into.

When young black dancers like Precious Adams and Michaela DePrince are told to bleach their skin, or that a black Clara in the Nutcracker isn’t something that people are “ready” for, Misty Copeland presents hope that they too can succeed.

There are black dancers, like Misty Copeland, and then there are BLACK dancers like Precious Adams and Michaela DePrince. It is my understanding that Precious Adams is now contracted to dance with the London Royal Ballet, and Michaela DePrince dances with the Dutch National Ballet and at the age of 19 is in her 3rd year as a professional dancer. Both girls have worked very hard to get where they are and each deserves 100% of the credit for getting where she is. Sorry to burst your bubble but Misty Copeland and her caramel colored skin did not open doors for either of them. Misty gives hope to the light brown girls, but I think that Precious Adams and Michaela DePrince offer hope to the BLACK girls.