Online Smack-Talking, Obsessing over the Islamic Scarf, and Angry Posting: How Muslim Women can Foster Dance to Pro-Actively Communicate Feminism

Question of the Day:

How does a Muslim woman go beyond “anger” or “projecting frustrations” on social media rants in a predominantly Islamophobic society through pro-active and meaningful ways that both address stereotypes and satisfy inner needs for emotional projection?

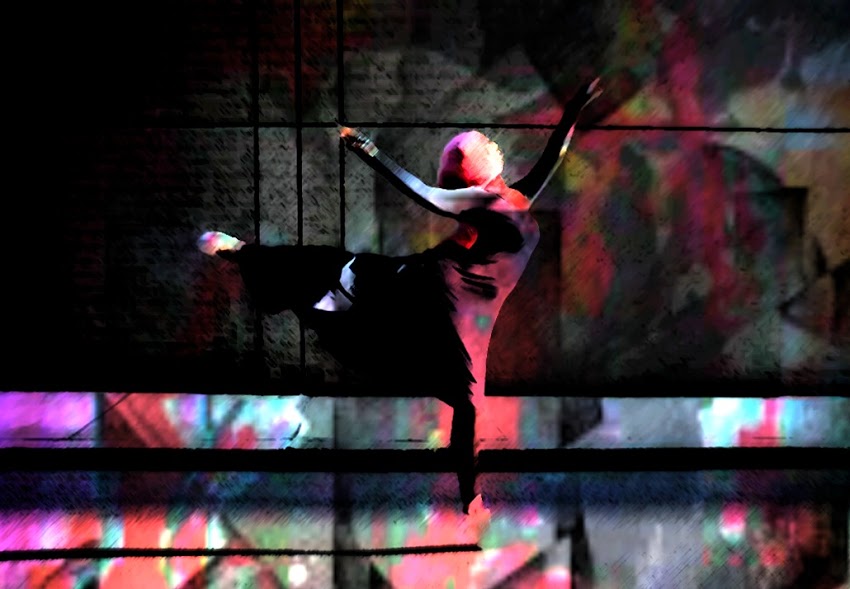

This weekend, I had the opportunity to “crash” the World Arts and Cultures (WACSMASH’D!) departmental event in which many dancers from the department were able to choreograph and perform their own work. Though I am not in the dance department, a specific dance called “For Puja” touched me beyond belief because what I saw answered my questions about outletting frustrations as a Muslim woman, while also inspiring a beautiful possibility of using the arts as means of community healing.

“For Puja” was performed by several women depicting powerful poses and movements consisting of complex leg-work. While the performers donned colorful and sequined scarves that flashed in the dimmed lights, what touched me were the powerful messages that included a section where the participants placed the headscarves on their heads. The headscarves were put on while maintaining strong stances which invoked a sense of self- power. It was clear through the facial expressions and deep equal-distanced stances that multiple identities ranging from Muslim or Middle Eastern/South-East Asian backgrounds were able to tap into familial roots while also partaking in an empowering and fluid identity.

It was a sad realization to me: I am one of the very few women in the department of World Arts and Cultures who identify as Muslim and also know the fact that not a single woman with the headscarf is either majoring or minoring in dance at UCLA. What does this mean for Muslim women in dance, and what does it mean for dance that their voice is not present?

The ways in which the performers were able to use their emotions, traditional yet modern, and powerful dances invoking images of self-confidence and assurance affected my heart because it’s often difficult to find outlets as a Muslim woman to reach out to others in ways that are productive in decreasing Islamophobia and addressing inner hurt from stereotypes of Muslim women as oppressed individuals. The dance itself forced me to ponder: what is the role of the arts in modern Muslim societies?

Many conservative movements ranging from Salafi to Wahabi ideology often depict dance and music as sources of “sin” by somehow stating that musical instruments (the cello, piano, saxophone, all of which were not even produced during the time of the religious quotes used in “support” of the argument) are an abomination. However, academic studies show that turning to the arts can produce beautiful meanings and symbolisms that achieve multi-tiered effects for both the audience and the performer.

Music and dance, especially within female groups during early Islam, were actually common– check out Dance (unfortunately, thanks to extremely conservative Muslim groups on the internet dominating websites, websites depicting fluidity on Islam and “controversial” topics like dance and music cannot really be found on mainstream pages but are extraneous in online book forms). Not only were women dancing, but women also danced in mixed gender groups and even served as drummers in battlefields during early Islamic periods.

When I look upon local Muslim communities, I see anger, frustration, and self-defeating methods of angrily tweeting or posting about how “stupid” some people are for seeing Muslims in a certain light. As a Muslim woman, I sometimes feel that constantly writing on topics like the “headscarf” or “Islam’s obvious feminism” are often like beating a dead horse, and I, too, am guilty in participating in this.

I see so many of my own contacts and friends caught up with trying to justify the freedom to wear or not wear the scarf and the ultimate meaning of peace, beauty, and love in Islam is often lost in these depictions of anger and frustration. I’ve even seen it divide up Muslim communities where women are labeled “The Feminists” to “The Religious Ones.”

When I saw the dance performance, I could not help but see unity between absorbing ones religion, one’s culture, and one’s upbringing in ways that foster knowledge, information, and connection between two characters: the sender and the receiver of knowledge.

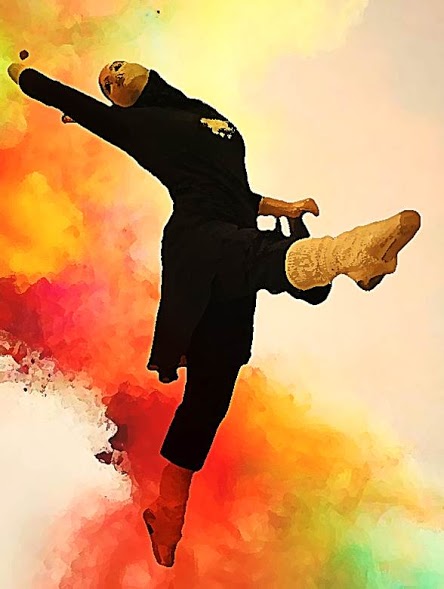

How many of us (and I ask this for all of us to ponder) have actively seen Muslim women partake in dance groups in public non-Muslim spaces? While I also have seen spoken word pieces that are beautifully performed by Muslim women, I see many of them separated by their own social groups and communities. Women who I know have a story to tell end up not telling their stories because of their fear of being outcast. How many Muslim women wish to partake in dance or the arts but feel it is one of those areas where they can be labeled as “sinners” or “non-religious”—even though dance has been recorded to be present in Islamic cultures since its beginning.

Some movements and groups are attempting to bring such topics to light and have even introduced women in niqaab to partake as dancers in public spaces. These topics and conversations make me ponder why local communities of Muslims in Los Angeles do not use dance more often and in public spaces not limited to just Muslims instead of often waiting for Islamophobic events to occur in order to protest it and return back to their lives. Even doing research on the internet about Muslim veiled women doing dance finds very few people that do so because of the huge stigma which is also prevalent on this campus.

If there’s anything I’ve learned from this WACSMASH’d event, it is the amount of dedication and strength it takes to not only rehearse every day for many hours, but also the perseverance it takes to give every show its equal value of work. And it disheartens me to think how it seems to me that my own communities don’t demonstrate this fastidiousness in making change pro-actively through the arts that engage an audience and give equal voicing to all Muslim women, often waiting for drastic events to occur to protest, boycott, and slide back into everyday life.

These performers in “For Puja” formed a piece that clearly empowered every individual in the room and evoked a sense of unity in understanding deeply hurtful and passionate subjects of self-identity. It reminded me that while language is powerful, spoken language has its limitations. As a Muslim woman, what do I do if I cannot translate my words, which are formed by multi-cultural communities and alternative worldviews, to another being who does not understand me?

While I run the risk of saying that “dance is universal,” I can at least hypothesize that the arts are another powerful source of communication that is too often disdained as “luxurious” and for “idle people.” I’ve too many times heard the benefits of arts and dance downgraded because of its lack of use in career; however, while this may or may not be true, using the arts and/or dance doesn’t have to be your career. From what I’ve learned, dance and the arts is a way of viewing the world and demonstrating yourself in ways that provide alternatives to spoken communication.

Oh, yes: since I also ran the risk of being a hypocrite, I joined a dance group that will be performing for the “Bicycling Asia Minor” exhibit on Greek, Balkan, Kurdish, and Turkish sema dances at the Fowler Museum next week. Come out and dance with us!

“Come, come, whoever you are. Wanderer, worshiper, lover of leaving. It doesn’t matter. Ours is not a caravan of despair. Come, even if you have broken your vows a thousand times. Come, yet again , come , come.” — Rumi/Mevlana