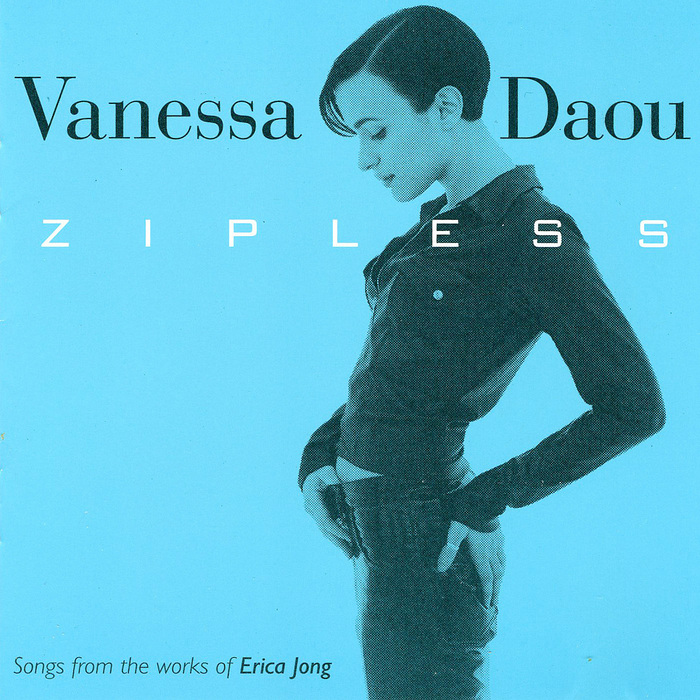

Album Review: Vanessa Daou’s “Zipless” and the Decentering of Men

Vanessa Daou, “Zipless” (1995, MCA Records/Krasnow Entertainment)

“The act of decentering men involves a stronger attachment to selfhood, found in relationship and solitude.” – Tabitha Prado-Richardson

When I read Tabitha Prado-Richardson’s Coalition Zine essay on decentering men from one’s own narrative, Vanessa Daou’s seminal 1994 album “Zipless” immediately sprung to mind. An LP-long interpretation of Erica Jong’s poetry, “Zipless” decenters men from Daou’s pleasure through an unabashed embrace of feminine sexuality and womanhood. Through “Zipless,” Daou bridges the concerns of second-wave feminism with those of then-burgeoning third-wave feminism.

From the opening moments of “The Long Tunnel of Wanting You,” the listener is plunged headlong into Daou’s sexually intimate space. In referring to her sex as a long tunnel, Daou suggests the pleasure received from its engagement transcends temporality. There is no door at the end of this tunnel. Daou and her partner can explore this tunnel for however long they can last. A further celebration of female sexuality continues on “Sunday Afternoons,” in which Daou pleasures herself to the memories of trysts with her unfaithful, transient male lover. Daou “[sits] at home / at her desk alone” as an act of ritual, space and time aligning to activate a specific and imperfect pleasure. “Near the Black Forest”, blends self-pleasure, partnered pleasure, and the external gaze into a laidback, late-night groove.

On the other end of the spectrum, “Becoming a Nun” turns abstinence into ecstasy. The narrator steels herself against “sex with it’s messy hungers” and “men with their peacock struts” by “[buttoning her] mouth against kisses” and “[dusting her] breasts with talcum.” She acknowledges “love with its pumping blood,” but the act of preserving herself becomes a pleasure in and of itself, a mirror of the pleasure achieved from the physical act of sex.

Daou associates female pleasure derived from the vagina with something beyond structured time. In addition to calling her vagina a long tunnel, she likens her pubic hair to a forest, natural and apart from the artificiality of patriarchal society. She, or rather the personae she inhabits, are at once metaphysical and material.

“Zipless” is unquestionably heteronormative. The pleasure she shares is with a male partner. However, these partners are rarely the subject. When speak-singing explicitly about sex, Daou forefronts women’s sexuality.

She investigates the internalization of patriarchy through “Alcestis on the Poetry Circuit,” where, imagining herself as a modern day Alcestis, Daou links the dismissive voice of the male gaze through literary irony and a mocking sense of self-awareness. In a further act of liberation, she confronts patriarchal negation outright in “My Love Is Too Much.” In it Daou coolly articulates the pleasure narratives of the men in their life, while alluding to the complexities of women that go unnoticed.

“Oh my love,

those simple girls

with simple needs

read my books too.

They tell me they feel

the same as I do.

They tell me I transcribe

the language of their hearts.

They tell me I translate

their mute, unspoken pain

into the white light

of language.

Oh love,

no love

is ever wholly undemanding.”

In the push to decenter men from their narrative, Daou intones:

“The love you seek

cannot be found

except in the white pages

of recipe books.

It is cooking you seek,

not love,

cooking with sex coming after,

cool sex

that speaks to the penis alone,

& not the howling chaos

of the heart.”

With “Zipless”, Daou uses Jong’s poetry to point to the fact that love and loving is rarely done with cleanliness. It is messy–loving someone else and loving one’s self. It will not be perfect, but as Prado-Richardson explains, “some particularly painful aspects of living cannot be redrawn under a simplistic narrative. . . but in my mind, self-romance . . . is wanting things to work out for yourself. It is getting in touch with hope and admitting that you do want the things that you want. It is feeling your desires, whether they be stagnant, anxious, or invigorating.” Through Daou’s album, we bear witness to the vicissitudes that come with placing oneself inside and outside the realm of sexual pleasure by decentering patriarchy, and the potential for liberation derived from its undertaking.