An Ode to the Library

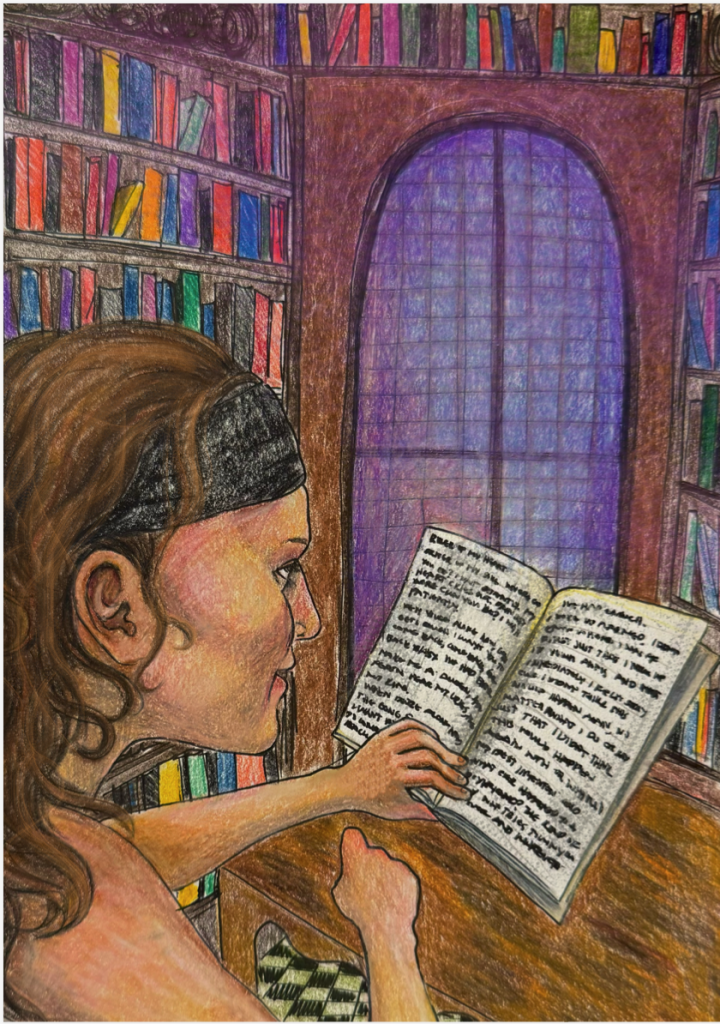

Image Description: “Lola Reading” A person reading a book in a library surrounded by tall shelves of books. A glass window is in the background with purple light shining through. The person has medium length brown hair and is wearing a black headband.

I think reading was my first love. What drew me to the act of reading was the tactile sensation of holding a book in my hands and the power the physical object had to immerse me in a world that was not my own. Naturally, the library became a haven for me. I would not be the reader, or person, that I am today without the library. I remember sitting between the stacks of my elementary school library staring in awe at the rows of books that loomed over me. The books seemed to represent all the possibilities of the world; this was simultaneously overwhelming and exciting to me. Even as a child, I was aware of the presence of the people that had read the book before me and I became obsessed with marginalia, or marginal notes. I clung to this evidence of previous readers as if they were sacred. The previous readers seemed to be my companions in the fictional worlds I inhabited, akin to a ghost or a spirit.

Libraries have always felt a bit spooky to me. The dust collects on the spines of books that have gone unread, and when the sunlight hits the floor in the right way and a stray draft stirs life into the once dormant particles, the same dust seems to dance under the sunbeams. Perhaps the same happens to ideas that have gone untouched. A new set of eyes stirs to life the ideas, characters, and worlds of an old book.

To this day, I crave the feeling of being completely devoured by a novel. Most of my life, both professionally and personally, revolves around literature in one way or another. I started working at the Interlibrary Loans Department (ILL) of the UCLA Library last year, which facilitates the exchange of materials between academic and public libraries for students to use. During my time here, I have considered working in libraries professionally.

The trope of the librarian has long been deployed in popular media to represent a frigid older woman who will yell at you if you make the slightest amount of noise. But maybe this figure represents a portal between the worlds of life and death. They are the guardian between what once was and the present moment. Because this is what the library represents to me, a place where one can wander among the energy of those who came before and inhabited the same space as us.

We’ve all heard that one George R.R. Martin quote, “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies . . . The man who never reads lives only one.” But maybe this relationship is not simply one sided. Maybe, the narrative lives on through the impact it leaves on the person even after they put it back on the shelf. Death and loss are inevitable parts of the human experience but maybe we can live on through the psychic presence we leave on the things that we love, including written texts, CDs, vinyls, and DVDs. I hope that when I pass my copy of The Color Purple or Percy Jackson will be donated to a used book store, a local library, or even sold in an estate sale. I hope that someone else can read my notes and look at my highlights and they can see where I laughed or where I cried. I hope that I can live on through my marginalia and that my spirit can live on through my presence in someone else’s library.

Fragments of history float through the filtered air. They breathe through the walls and get to live on through the energy of those that pass. The library has become a home of sorts, their presence makes the building so much more than just a physical space. And in turn, they become so much more than fragments to be lost to the whims of history.

Libraries are memory institutions in the same way that museums are. Academic libraries often run archives and curate special collections, acting as a literal form of memory preservation. Community public libraries function in the same way. I believe that when you hold the same book or watch the same dvd or listen to the same CD that someone else has also loved, they leave a psychic imprint on the material. Rather than literal materials, public libraries trade in the realm of the ephemeral. They preserve a whiff of perfume left by a lingering hand while glancing at a book jacket permeates the pages. The sound of two lovers’ laughter as they argue over which DVD to rent echoes off of the walls and fills the whole room with life. The awe on a child’s face as they sit crossed legged during storytime and the lasting impression this smile will leave on the librarian. While none of these things are literal objects that one can input on a database or shelve on a wall, they are equally important in shaping the library.

When public libraries house these ephemera that are shared by the community broadly, they become the archives and preservers of people’s lives and experiences. How beautiful it is to hold a book in your hands and know that someone before you has held and loved it the same.To know that they walked between the same stacks and used the same computer and drank out of the same water fountain. To know that they inhabited the same world as you even if for just a fraction of time.

But what about the pieces that are lost? What happens to the histories that aren’t deemed important enough to remember? Or histories that are purposefully discarded?

If knowledge is power, then how we organize it is everything. Libraries are sites of power. Libraries have the authority to decide which histories are important, which pieces of material should be saved. This responsibility shapes the way that knowledge is conceptualized. In recent years, there has been a shift to recognize the way that archives have failed marginalized histories. Scholars are finding ways to read against archives in order to find the histories of marginalized people. But as much as we would like to, we cannot go back in time and re-do the documentation of history. How can libraries remedy this error in the present?

Public libraries often provide essential services to marginalized members of the community, whether that be a warm place to be during a cold day, access to a computer to complete a job application, or adult literacy classes. By providing these services, public libraries have the potential to help right this wrong. Public libraries are capable of facilitating the power that comes from community building and free knowledge exchange.

When I first started working at the ILL, the idea that we were the people responsible for facilitating this exchange of knowledge made me weepy. I have been known to assign excess meaning to mundane things, but this job felt like the culmination of all that I believe in. As the days dragged on though, I realized the job can become tedious. It’s a lot of computer work and opening mail. But, my favorite part about the job though, is when we get a little note with a cute little graphic thanking us for letting them borrow our materials. Especially when they are from small public libraries. Or sometimes, we’ll get handwritten notes from people about how they used to go to UCLA or even how they lived in California at one point or another. One time, we received a package of about 10 books accompanied by a handwritten note from the sender saying that she had checked these out while she was in school but never returned them. I carefully collect each of these in my journal. I consider it to be my own little archive of the goodness of humanity and the never-ending desire to connect with each other. These little pieces of humanness embedded within the books, and within the bureaucracy that is the UCLA Library, makes me emotional. I feel like I am in contact with the people, and the love, that came before me in order for these books to even exist. I continue to fall in love with libraries the older I get because they feel like memorials to human experience.