Banana Republic: The U.S.’ Violent Pursuit for Hegemony

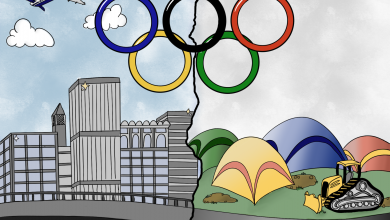

Design by Grace Gibbons

Image description: Images of bananas, the flag of Guatemala, advertising for Chiquita Bananas, and the Chiquita logo are displayed in a collage.

Today, the term Banana Republic is explicitly recognized by many in the U.S. as an upscale clothing store. However, it also holds an implicit familiarity as an exoticized notion of life in Central America. Fantasies about the land where we source our bananas have roots in the machinations of American imperialism and reflect centuries of harm communities endured in the battle for hegemony. Through the disparaging pursuit for empire, bananas became a metaphor for unbridled capitalism in the construction of the banana republic, a term coined by O. Henry in “Cabbages and Kings” that refers to “a country with an economy of state capitalism, whereby the country is operated as a private commercial enterprise for the exclusive profit of the ruling class” (Henry, p. 157, 1904).

While it had been exercising its colonial reach for centuries prior, the United States formally institutionalized itself in Honduras in 1899 when it established the United Fruit Company – affectionately known today as Chiquita Bananas. The corporation spearheaded Honduras’ political-economic relationship with the U.S., establishing plantations and instability throughout the country and its neighbors in Central America. Its violent history of coups, exploitation, and climate destruction was juxtaposed in the U.S. with romanticized imagery of tropical life in the banana republic.

Throughout the early 1900s, Chiquita rapidly expanded into South America through deregulating environmental and labor policies in exchange for its invaluable investment. As the number of people employed by Chiquita rose, so did the company’s labor rights violations, and it became clear very quickly that the priority of the company did not lie with its local community. Despite Chiquita’s hostility, movements to protect workers rights continued, and in 1928, workers staged one of their largest strikes in Colombia. The “friendly” banana retailer responded by enlisting the help of the U.S. government to quell protests, and military-backed repression swiftly ended the strike, killing an estimated 2,000 people and ensuring the growth of an empire by establishing a corporatocracy.

As U.S. imperialism established itself into the 20th century, Chiquita’s interventionism grew alongside it. In the 1930s, entrenchment of the corporate state was so deep that Guatemalan President Jorge Ubico used forced Mayan labor to generate profit from Chiquita, which owned 1 million acres throughout Central America at the time – over half of its land. Simultaneously, the U.S. constructed the Soto Cano military base to amplify its ability to exercise control. Throughout this time period, the U.S. equipped the region for ceaseless exploitation through neoliberal policies that privatized public resources, dispossessed land, and militarized societies. The infiltration of the region during the Cold War was so pervasive that Central America became known as the “U.S.S Honduras” for its positionality as a capitalist acolyte in the Gulf of Mexico.

As the 1950s progressed, Chiquita weaponized McCarthyism to tighten its grasp on the banana republic. At the crux of the Cold War, Guatemala elected a new president, Jacobo Arbenz, on the promise of land and wealth redistribution for Native Guatemalans. When Arbenz confiscated Chiquita-owned land as part of his land directive, U.S. President Eisenhower launched a coup in retaliation. Painting Arbenz as a dangerous communist, the official U.S. line was that Guatemala was undergoing a revolution, while the CIA-led coup “Operation Success” overthrew Arbenz in 1954. Arbenz’s replacement illustrates the power of the swift, systemic hand who acts quietly to suppress subversives that challenge capitalism.

Arbenz’s violent ousting replaced him with President Carlos Armas. Endorsed by the U.S. government as the pinnacle of democratic values, Armas catalyzed years of social instability throughout Guatemala; dismantling unions and arresting suspected communists. At the same time, Chiquita sales boomed as they spoon-fed U.S. consumers sanitized propaganda about what life was like closer to the equator, even sending cruise liners of contented Americans to coastal Central American towns — reveling in the beauty of tourist destinations that were protected by our honorable fight against communism. Chiquita later lent these cruise ships — alongside direct donations — to support the Bay of Pigs invasion, the military operative that attempted to oust Fidel Castro from power in Cuba.

Nearly 50 years later, the political might of Chiquita had only grown, and their embeddedness in politics was well understood throughout the region. When democratically elected Honduran President Manuel Zelaya attempted to increase the minimum wage, Chiquita feared for their profits. The all-mighty political corporation mobilized alongside members of the Honduran transnational capitalist class to see an end to Zelaya’s power. With help from the U.S. government, Chiquita’s worry was soothed as US-trained military groups abducted Zelaya in 2009. They replaced him with undemocratically elected President Sosa, who became known for election fraud and instigated years of social unrest — much to Chiquita’s indifference. Ten years later, bananas remain the U.S.’ most widely consumed fresh fruit, and Chiquita controls nearly 30 percent of the banana market — more than any other company.

By nurturing systems faithful to the American empire, the U.S. institutionalized the banana republic to secure their hegemony in global capitalism. Sanctioning decades of violence to establish a corporatocracy ensured Honduras’ perpetual dependency on the U.S.’ neoliberal system. In the same way that the U.S. bombs countries and leverages eternal payment plans to rebuild them, Chiquita fostered a corporatocracy perennially dependent on the U.S. Over 40 percent of Honduran exports now go to the U.S., a large proportion of these being bananas, establishing a large vulnerability when seeking economic independence.

Earlier this year, former Honduran president Juan Hernández was being tried in U.S. court on accusations of complacency in drug-trafficking to the U.S. Convicted on Friday, March 8, Hernández faces life in prison and was shamed by prosecutors because he “abused his position;” declaring that no one — despite their power — should be above the law. The U.S.’ righteous pursuit of justice in this case follows a decade of unwavering support for Honduran leaders, prompting questions of the true motivations for Hernández’s trial. If the U.S. was sincerely passionate about prosecuting drug crimes and protecting citizens from corrupted leaders, why did they legitimize Hernández’s reelection in 2017 despite widespread claims of fraud, and send his regime millions of dollars in military aid?

Rhetorical questions of the U.S.’ hypocrisy front the brains of many Hondurans watching the trials and illustrate a clear claim of the U.S. only engaging with human rights violations when it is politically advantageous. The U.S.’ ruthless pursuit of hegemony is encapsulated in Chiquita’s 100 year long pursuit of corporatocracy in the banana republic and is emblematic of a political-economic system that operates by subjugating its people. Under these conditions, the unassuming, impartial banana became a means to an end in a violent capitalist venture, destabilizing ecosystems of people and nature. And while no other country in the world gets to champion the American dream, no other country in the world views death and destruction as collateral in the pursuit of a banana.