Feminism 101: What is Emotional Labor?

Design by Breana Lee

Have you ever felt drained after working to continue smiling at disrespectful customers or faking interest in a coworker’s relationship issues? This type of effort has a name: emotional labor.

Sociologists have studied the concept of emotional labor since Arlie Hochschild first introduced the term in 1983. Hochschild studies emotion work, or the work required to manage one’s feelings or maintain social relationships in everyday life. She argues that as the economy has become dominated by the service industry, employers have increasingly demanded emotion work from their employees, turning it into a marketable service known as emotional labor.

This type of labor takes a mental toll on employees. Emotional labor in the service industry is an expectation, not a suggestion. Rather than being paid extra for their effort, low-wage employees are often punished for forgetting to smile or appearing disingenuous in their cheer.

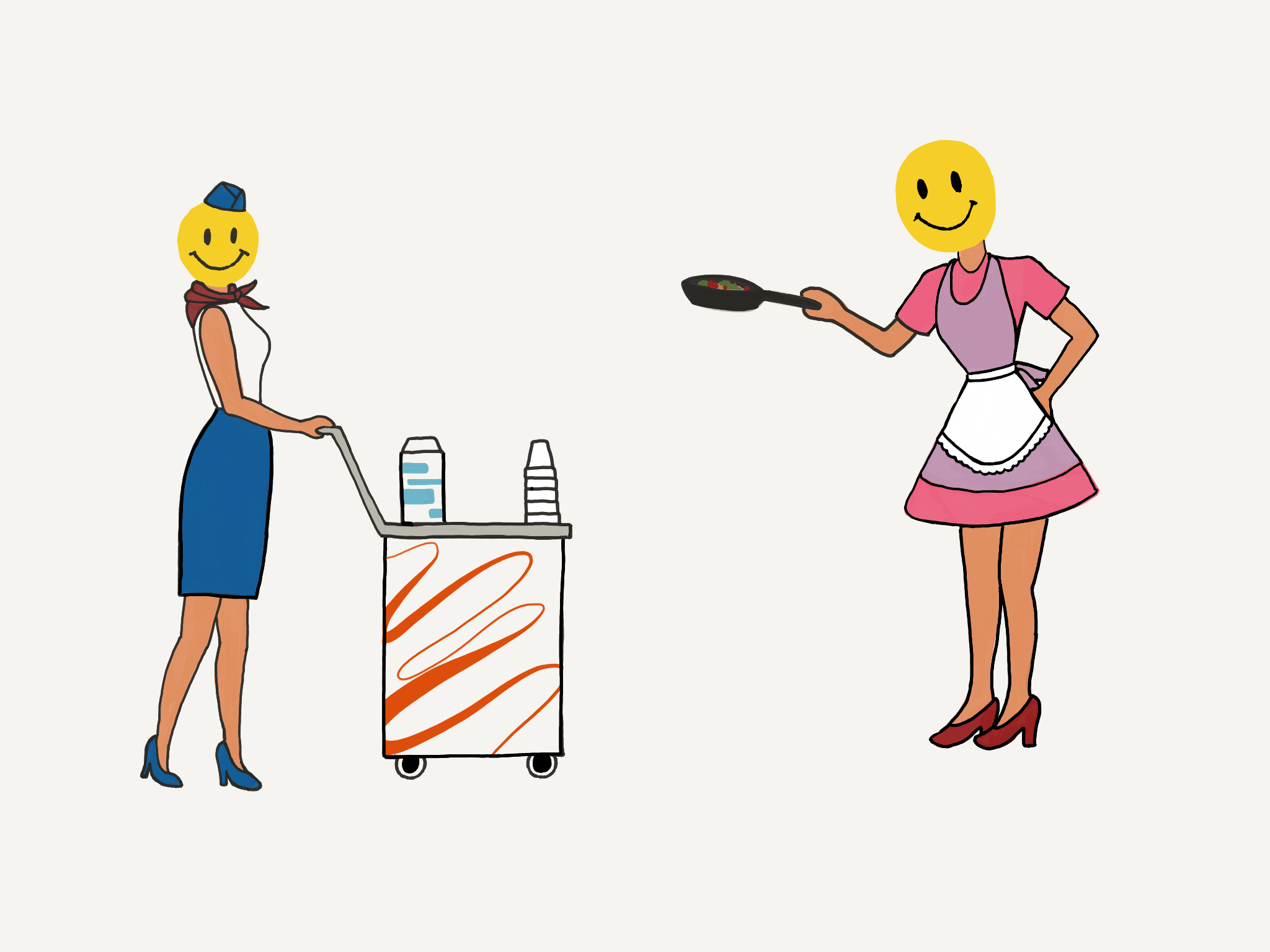

Furthermore, a job’s emotional expectations can perpetuate gendered assumptions about character traits and career choices. For example, Hochschild discusses the emotional labor required of flight attendants, who strive to maintain a pleasant, caring demeanor in order to provide a satisfactory experience for airline customers. As the role of flight attendant was conflated with the stereotypically feminine act of nurturing, being a flight attendant came to be seen as a “woman’s job.”

Emotional labor has recently resurfaced in feminist discussions as a concept relevant in everyday relationships as well as the workplace. For example, women are often forced to deal with the emotional burden of other people’s problems, which can have a taxing effect similar to that felt by employees in the service industry. Women are also frequently expected to appear empathetic and concerned for others while simultaneously suppressing any emotion that could be used to dismiss them as irrational or hormonal. These socially-inscribed daily tasks are forms of emotional labor that encompass and expand upon Hochschild’s original conception.

The household and home environments also demand emotional labor. Between heterosexual couples, the division of domestic work is often uneven, with women performing not only the bulk of household chores but also the day-to-day management of the home, such as keeping track of family members’ schedules. Women who seek help from their partners are often read as nags, adding to the stress they are already experiencing. These acts cross the line between emotion work and emotional labor because women are expected to carry out these tasks without question or reciprocation from their partners.

As emotional labor becomes acknowledged in an increasing number of social arenas, its definition has become less agreed-upon. Critics alleging overuse of the term provide a strict definition of emotional labor as emotion management, preferring to label issues like the stress of scheduling as “clerical labor.” However, a mother tasked with managing her family’s schedule is experiencing a different type of stress, due to the emotional ties and dependance involved with family, compared to someone who schedules other employees for a living.

Despite differing views on what can be considered emotional labor, it is clear that our current economy does not value such work. The call for wages for housework has been present in feminist activism for decades but is still widely dismissed by the majority of the public. Although health aide jobs are growing the fastest, their wages remain among the lowest, despite the high levels of emotional labor required for caregiving work. Within close friendships, the energy expended on sympathizing and giving advice is expected, even when not explicitly demanded or reciprocated. Our social and professional circles continue to call for emotion work and emotional labor without recognition of the effort they require, and it has a real effect on our wellbeing.

Until emotional labor is universally recognized and compensated, whether monetarily or mentally, the everyday emotional strain of people — predominantly women — will go underappreciated.