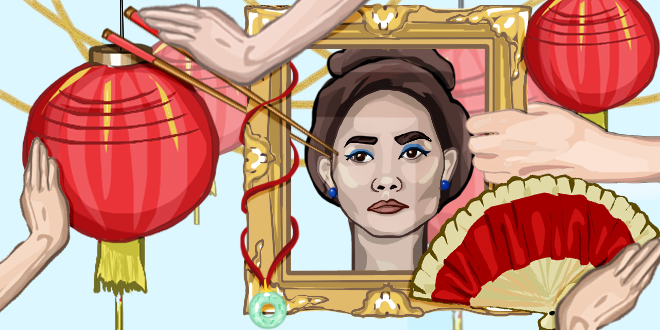

Feminism 101: What is Orientalism?

Design by Emma Lehman

Initially coined by Edward Said, Orientalism is the West’s construction of stereotypes that regard Eastern people and cultures as backwards, exotic, and passive. The role of “the Occident” is assigned to the West, specifically the U.S. and Europe, while Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa are cast as the elusive, strange, “Orient”. Under this binary, the hegemonic West regards the East as a regressive, inferior entity as a justification for imperialist intervention.

The origin of this “West vs. East” narrative can be traced back to the age of Enlightenment, when Christian missionaries from Europe encountered Arab cultures and the Islamic faith during their colonial conquest. As a consequence, the Europeans, blinded by their Eurocentrism, formed prejudiced assumptions that these people were barbaric in comparison to the West.

This essentialized version of the East was constructed for the West, by the West. Colonialism in particular has been a primary force in shaping the discourse surrounding Orientalist thought, which is underscored by the desire to subjugate. This narrative is laced with power: it is shaped by the West’s heinous tendency to subordinate otherness through exploitative, self imposed authority. The narrative of the East as a foreign inferiors awaiting correction has enabled Western nations to forcibly occupy other countries, oppress their people, and extract resources.

However, it should be noted that Orientalism is not a one-dimensional concept, nor is it solely theoretical in practice. It has and continues to operate in a number of ways, each of them harmful in their own respect. Institutions such as the mass media and the U.S. government are guilty of subsisting on Orientalist stereotypes that pander to society’s generalized constructions of the East and advance their own agendas.

For example, Asian women have been bound to exoticized depictions as mysterious, sensual, and erotic beings. Several Orientalist motifs that romanticize “Eastern” women may come to mind: snake charmers, veiled women, and belly dancers are all common archetypes depicted in 19th and 20th century art. The hypersexualization of Asian women, who have and continue to be objectified as submissive, sexual objects in the mass media, can also be attributed to these stereotypes.

By relegating the East to a submissive, homogenous caricature of otherness, Orientalism has served as a device for the West to preserve its role at the top of the global hierarchy, engendering imperialism and violent conquest around the globe. This type of discourse has proven to be especially instrumental for the U.S., as it serves as justification for the U.S. to meddle in Middle Eastern countries and wreak havoc.

In the wake of 9/11, the Bush Administration’s “War on Terrorism” resulted in the U.S. government opportunistically capitalizing off of the public’s trauma and reducing Islam to an inherently anti-Western threat. Soon, the government and mass media force fed this generalization to the American public, which further entrenched the “us” vs. “them” binary into many people’s worldviews. This type of rhetoric invoked prejudice against Muslims and provoked many Americans into supporting violence against countries in the Middle East.

The U.S.’s military intervention in Iraq is arguably the most salient manifestation of Orientalism in the 21st century. In 2003, the U.S. invaded Iraq on the basis of a false assumption that the country possessed mass weapons of destruction. This excuse, along with U.S. militarism under the guise of freedom, perpetuated the narrative that the Middle East as a monolithic entity posed a threat to the “modernity” of the West. In retaliation to 9/11, countries such as Iran and Iraq were framed by the U.S. as “anti-democratic” threats to global security.

Equally as consequential is the U.S.’s outdated conviction that democracy is a unilateral antidote for “otherness,” which rationalizes violent conflict in the Middle East. This is rooted in Orientalist sentiment, which denies people from Eastern cultures of their agency and their right to a valid existence. Furthermore, this type of rhetoric does nothing to challenge centuries of people of color’s oppression at the hands of Western powers. Instead, it maintains the status quo of the U.S.’s existence as a global hegemon, forcing itself upon countries deemed as inferior.

In his essay “Culture and Imperialism”, Said urges us to denounce imperialism: “…this also means not trying to rule others, not trying to classify them or put them in hierarchies, above all, not constantly reiterating how ‘our’ country or culture is number one.” Western nations have a monumental lesson to learn from this, along with unpacking their historical tendency of assuming that other civilizations are “backwards”, and therefore receptive to subjugation.

Cultures that are unfamiliar to us should not be regarded as monoliths. Orientalist language encourages reductionist binaries. It is polarizing and enables institutions like neoimperialism to continue operating as belligerent machines of oppression. Instead of viewing the world through a Eurocentric lens, we must strive to denounce stereotypes that uphold these institutions and actively work towards dismantling them.