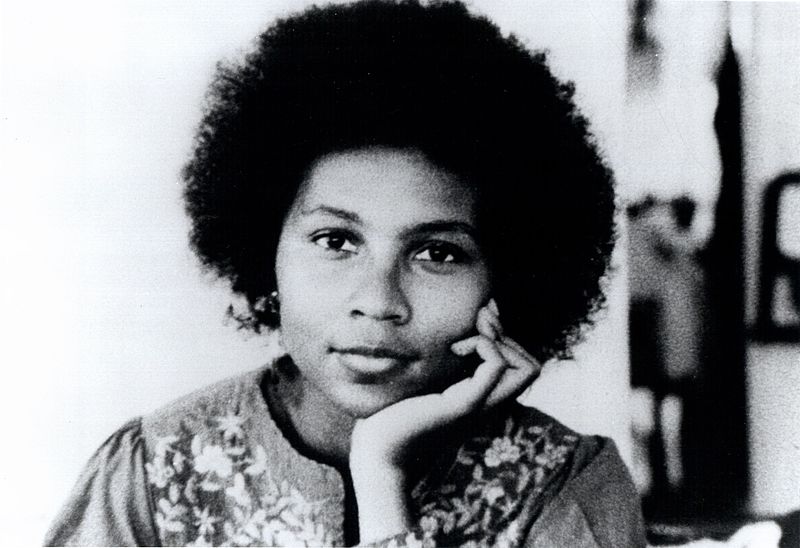

Feminist Theorist Thursdays: bell hooks

Image from Wikimedia Commons.

bell hooks is a Black feminist theorist, professor, and cultural critic who has authored over 30 books, in addition to dozens of personal essays and scholarly articles. Born Gloria Jean Watkins, hooks chose her pseudonym to honor her maternal great-grandmother, Bell Blair Hooks. hooks’ name is always written in lowercase in order to emphasize the substance of her work over her person. Her work explores themes of Black feminism, education, and community activism, with a marked emphasis on the intersections of race, class, and gender.

hooks, who published her first book in 1981, was one of the earliest figures in the second-wave women’s movement to condemn the racism of mainstream feminists, and to call for a more intersectional feminist vision. She has since established herself as a highly influential writer and has made invaluable contributions to the canon of feminist thought.

hooks was first exposed to the feminist movement in the early 1970s, as an undergraduate student at Stanford University. She attended a women’s college for one year before transferring to Stanford, and she was shocked at the difference in attitudes toward women’s abilities. “[At Stanford] we were told time and time again by male professors that we were not as intelligent as the males,” hooks later noted. “My ability was constantly questioned. I began to doubt myself.”

hooks continued to develop her feminist consciousness both inside and outside of the classroom. At the age of 19, hooks began writing her first book, “Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism,” though it was not published until 1981. “Ain’t I a Woman,” which hooks titled after abolitionist Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, examines the historical interaction of sexism and racism during slavery and their lingering impact on Black women. hooks also criticizes the mainstream second-wave feminist movement for its failure to represent working-class women and women of color.

The lack of intersectionality within the mainstream feminist movement is a recurring theme throughout hooks’ later work. In her 2000 book “Feminism Is for Everybody,” hooks recounts the development of the second-wave feminist movement as it strayed from its revolutionary roots into a depoliticized, reformist vision. As the movement gained traction, she explains, increasing numbers of privileged white women saw feminism as a means of obtaining equal status with privileged men. This gave rise to what hooks refers to as “lifestyle feminism,” the idea that a woman can be a feminist regardless of her political ideology.

Instead, hooks defines feminism as “a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.” This definition, which first appeared in her 1984 book “Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center,” centers the most marginalized women in the movement, and makes clear that any actions taken in the interest of white supremacy or class mobility are not aligned with true feminism.

Another recurring theme in hooks’ writings is education. hooks considers education vital to radical social change, referring to “the university as a central site for revolutionary struggle, a site […] where we can have a pedagogy of liberation.” To hooks, education is fundamentally political; education provides a space for female and Black students, who have historically been denied access to institutions of learning, to develop critical consciousness and to challenge hegemonic ideas.

hooks, however, is careful to acknowledge the historically inaccessible nature of higher education. “The academy was and remains a site of class privilege,” she writes, noting that the majority of academic feminist discourse is written “in a sophisticated jargon that only the well-educated can read.” hooks calls instead for a critical pedagogy oriented around accessibility, transformation, and community learning.

hooks brings this philosophy to her own work, using clear, accessible language and eschewing academic conventions such as footnotes or bibliographies. Though her writing has been criticized as “unscholarly,” hooks argues that her style is a political choice, “motivated by the desire to be inclusive.”

hooks’ own teaching career began at the University of Southern California, after she completed her doctorate in English literature. She began teaching English and ethnic studies, and has since taught at a number of institutions including Yale University, Oberlin College, and the University of California, Santa Cruz, in departments such as women’s studies, African American studies, and Appalachian studies. hooks is currently a Distinguished Professor in Residence at Berea College, in her home state of Kentucky. She continues to teach, write, and speak publicly.

Since the publication of her first book, hooks has become a well-known voice in the feminist movement. Her clear, accessible writing and visionary politics have made her a staple in women’s studies curricula, and she will likely remain so for years to come.