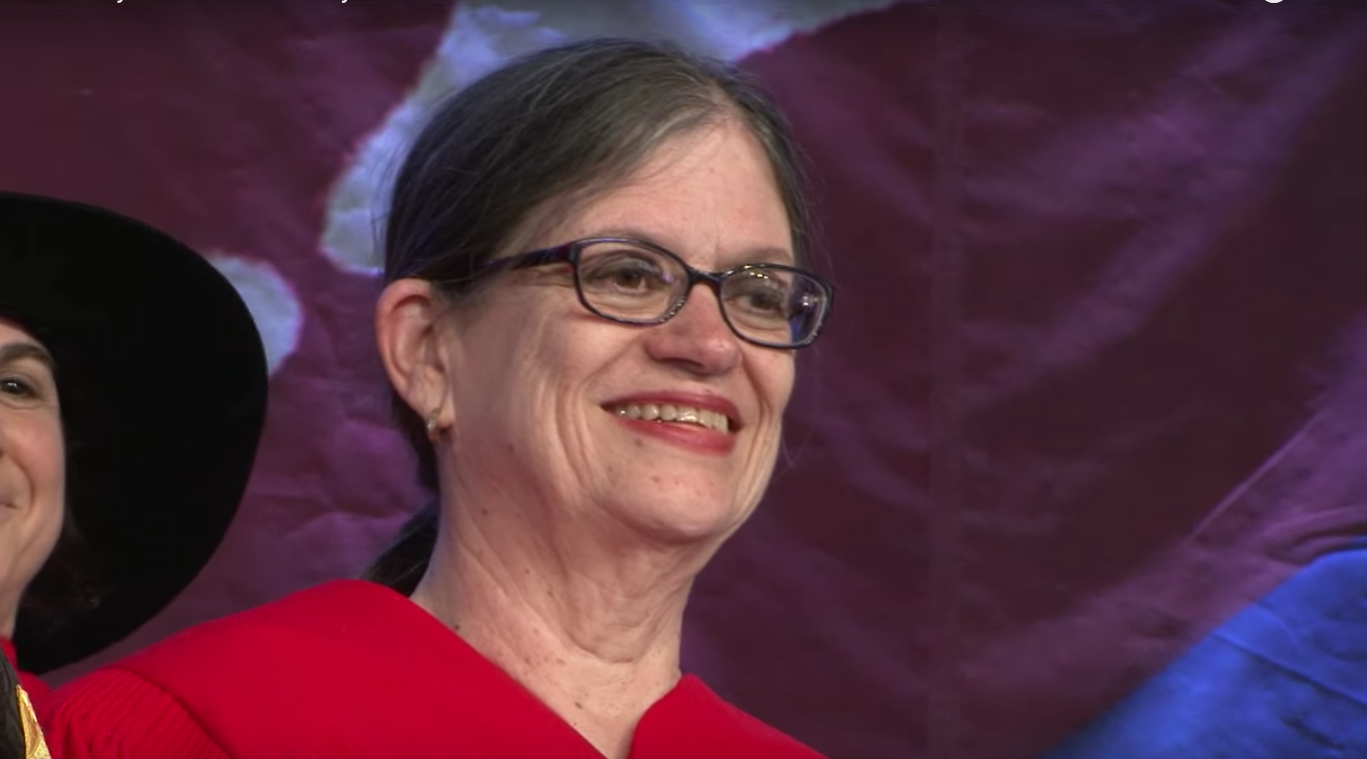

Feminist Theorist Thursdays: Susan McClary

Image by McGill University via Youtube / CC BY 2.0

Susan McClary is one of the most important musicologists responsible for introducing feminist critique to musicology. Her work, though controversial, was some of the first to present a critique of Western classical music that considered the role of gender and sexuality.

Born in 1946, McClary received her B.A. from Southern Illinois University, and her M.A. and Ph.D. from Harvard. She taught music and musicology at University of Minnesota, McGill University, UC Berkeley, UCLA, and University of Oslo before becoming Head of Musicology at Case Western Reserve University. Her best known book is “Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality,” which refers to the masculine nature of Western classical music and the otherization of femininity.

As Simone de Beauvoir wrote in her book “The Second Sex,” “There is an absolute human type, the masculine.” The masculine represents the standard, whereas the feminine is the deviant other. McClary describes Western classical music as representative of male sexuality and sexual behavior. In the context of Western tonality, femininity again is a deviation from the norm. So where do women fit in the “phallic economy” of Western classical music?

According to McClary, Western classical music is based on the narrative of the masculine conquering the feminine. One instance of this narrative that is prominent in McClary’s work is sonata form.

Some background: Sonata form is a compositional style that usually involves two main melodies, called themes. There is a primary theme and a secondary theme. The primary theme is in the main key of the piece and has a strong cadence, or ending. The secondary theme is more lyrical and, in the beginning of the composition, is in a different key. At the end of the composition, the two themes are repeated, and the secondary theme takes on the key and strong cadence of the main theme. This ending—the consolidation of the key and strong ending—functions as a satisfactory closure.

Sonata form historically has constructed gender by presenting the stronger primary theme as masculine and the lyrical, deviant secondary theme as feminine. This is consistent with de Beauvoir’s assertion that the masculine is the absolute type while the feminine is the other.

McClary interprets the consolidation of the secondary theme into the primary theme as representative of the subjugation and domestication of the feminine by the masculine. In this way, the form reflects patriarchal structure in society.

In her writing, McClary doesn’t specify whether she believes composers are aware that this is the implication. Her work operates under the idea that music is reflective of society. In other words, music is always influenced by what is going on around it when it is composed or performed. But regardless of whether composers are aware of the patriarchal implications of the sonata form narrative, the patriarchal society in which they are composing and their binary concept of gender influence their compositions.

Of course, McClary’s work is not devoid of problems. Her interpretation of classical music and sexuality is based in a binary view of gender, whereas in reality gender is much more complicated. She also tends to present feminine sexuality, a term McClary uses to describe women’s sexual behavior, as uniform across all women.

Despite her problematic view of gender and sexuality, McClary’s work helped to introduce feminism to musicology, a field that previously had been exclusively concerned with the white male point of view. She wasn’t the first feminist music scholar, but, unlike previous feminist musicologists, she went beyond simply bringing attention to women in music. Instead, she brought feminist ideas to music critique and was able to achieve popular appeal through her direct condemnation of the masculine hegemony in music.