Free to Sell Sex but not to Buy It: Looking Back on France’s Controversial Prostitution Law

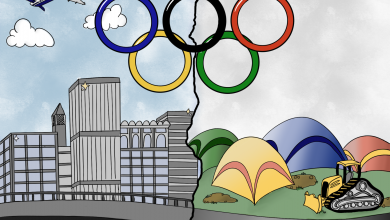

Image by Simone Montgomery

Note: In this article, prostitution refers to the exchange of physical sexual acts for money. Sex work is a broader term that encompasses prostitution as well as no-contact sexual performances. I use prostitution in this article to maintain the specificity of this experience and because of its use as a legally precise term.

In April 2016, the French National Assembly passed legislation that penalizes the purchase of sex and overturned a 2003 law punishing public solicitation by prostitutes, following the lead of Sweden and other Nordic countries. The law also forces clients caught by law enforcement to attend classes about the dangers sex workers face and establishes a transition program providing cash stipends and other aid to prostitutes seeking to leave the industry. Undocumented prostituted individuals in these exit programs may now obtain temporary residence permits that allow them to find legal employment in France, a critical measure as 85% of France’s estimated 30,000 to 40,000 prostitutes are victims of trafficking, with most from Eastern Europe and Africa. Over 85% of prostitutes in the country are women and nearly 100% of those purchasing sex are men.

One year later, activists are divided about the law’s results. Around the anniversary of the law’s adoption, almost 200 sex workers in Paris demonstrated against the law by marching out of the Place Pigalle, a historic red light district in Paris. Thierry Schaffhauser of STRASS (Syndicat du travail sexuel), France’s sex worker union, claims that client criminalization has created “more pressure to decrease our rates or accept sex without condoms” and that street-based sex workers still face criminalization “under local bylaws, procurement laws, and anti-immigration laws.” The International Committee on the Rights of Sex Workers in Europe (ICRSE) argues that the law’s 4.8 million euro budget is insufficient and the exit program merely functions as a “‘smoke screen’ to hide the [law’s] punitive objective.”

Others have celebrated the law’s anniversary and demanded more effective enforcement. Abolition 2012, a coalition of 62 feminist organizations supporting the eradication of prostitution, praised the progress France has made, with the number of prostitutes arrested for solicitation down from 1,500 a year to zero since the law’s implementation. In a press statement, Abolition 2012 called for a substantial increase in funding for exit routes to ensure their success and asserted that its component organizations would initiate legal proceedings against municipal laws that ban prostitution. Coalition for the Abolition of Prostitution, or CAP International, applauded France’s “recognition of physical and sexual violence against a prostituted person as an aggravating circumstance,” a legal circumstance used in several trials in the past year. In France, the risk of rape for prostitutes is six times greater than for the general population.

The controversy over the criminalization of buying sex in France is part of a larger debate among activists over legal solutions to the abuses of the prostitution industry. Those who believe the law hurts sex workers typically back the full decriminalization of prostitution (both selling and buying) instead, following the model of New Zealand in which prostitutes have access to workplace protections and healthcare. Some may even support the option of full legalization adopted by Germany. According to the Sex Workers Education Network, the process of decriminalization provides the groundwork for individuals to “assert [their] right to work as prostitutes” and “claim their right to freedom of choice of management.”

Supporters of the law often take an abolitionist perspective and endorse the end-demand approach carried out in Nordic countries. Abolitionist NGO organization CAP International analyzes prostitution as “a form of exploitation of inequalities” that “reinforces the objectification of all women and their bodies…by placing the human body and sex into the realm of the marketplace.” Though groups taking either position explicitly denounce the stigmatization of and widespread violence against sex workers, they disagree on the fundamental question: should prostitution exist?

The often-repeated decriminalization slogan “sex work is work” expresses efforts to reframe prostitution as a legitimate economic activity that should be treated as any other exchange. Amnesty International, a supporter of the full decriminalization of prostitution, distinguishes sex work from trafficking as “consensual adult sex…that does not involve coercion, exploitation or abuse.” In a paper by the Global Network of Sex Works Projects, the organization claims that the Nordic model in Sweden depicts prostitution as “inherently victimizing” because it does not legally regard prostitution as “chosen work” like other occupations. The logic behind the primary decriminalization argument is a classical liberal one in which self-determination and individualism are the values in operation. The defense of prostitution in the abstract stipulates that individuals have agency and possess a right to freely exchange sex as a service on the market.

Abolitionist activists attempt to problematize the concept of perfect consent, and by consequence, the distinction between sex work and trafficking. In addition to explicit coercion and threats of violence by pimps, prostitutes who work primarily on the street level face structural barriers to leaving the industry, including economic necessity, lack of job skills and formal education, criminal records, and lack of documentation. One study reports that up to 89% of sex workers want to leave the industry but are unable to. Executive director of Girls Education and Mentoring Services (GEMS) Rachel Lloyd argues, “It may be true that some women in commercial sex exercised some level of informed choice [and] had other options to entering…but, these women are the minority and don’t represent the overwhelming majority…for whom the sex industry isn’t about choice but lack of choice.” Prostitution abolitionists, without imposing a value judgement on sex workers themselves, question how agency is meted out within a society structured by economic and gender inequalities.

Abolitionists share a fundamental objection to the commodification of – without making a gross generalization – what is almost always women’s sexuality by men. Some frame this objection in moral terms, interpreting the industry as a system of women’s objectification that violates one’s intrinsic “physical and moral integrity.” Anti-capitalists condemn prostitution as an exceptional kind of labor exploitation, one that historically “is not just an ‘intersection’ but a co-development in the ideological systems of capitalism and patriarchy which have come to reinforce each other’s existence.” These analyses of prostitution as fundamentally gendered conflict with the decriminalization argument that sex work ought to be understood like other “legitimate” work. To put it succinctly, abolitionist activists fear that the legalization of prostitution – and thus the creation of a labor model – reduces the assault and rape of sex workers to “occupational hazard[s],” rather than violence against women.

In answering the theoretical question of should sex work be work, we as feminists must first concern ourselves with the material effects of proposed legislative changes on prostituted individuals. The assertion that we should simply “listen to sex workers,” though earnest in intent, fails to capture the incredibly diverse experiences and relative social locations of people who fall under the category of “sex worker.” A white woman in the United States whose sex work consists of no-contact online performances or escorting should not dictate a global conversation about an industry that primarily operates in the underground street economy. It is critical to pay attention to the day-to-day lives of sex workers without reducing them to ideological mouthpieces.

Abolitionists and decriminalization advocates alike have a genuine interest in the well-being of sex workers. However, any legal proposals aimed at harm reduction or abolition alone will fail society’s most vulnerable without a holistic approach to the industry. Well-funded exit programs, job training programs, accessible health care, immigration laws, police retraining, public awareness efforts, and a strong social safety net all determine the effectiveness of policy. France made a bold statement about the ethical status of sex work in 2016, but must now follow through with continued support for the women, men, gender-nonconforming individuals, and children in prostitution.