Funding the Rising Costs of Higher Education: Comparisons Between the Illinoisan and Californian Systems

Image of Janss Steps, UCLA by brent via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0

On July 6, the Illinois House voted to break the state budget impasse which affected Social Security, Medicaid grants, and university funding for over two years. Sen. Dale Righter, the sole Republican to vote in line with the Democratic House, cited the effect of the lack of state funding on Eastern Illinois University’s campus, shedding light on a long-standing issue of rising costs of education and universities’ dependence on state and federal funds.

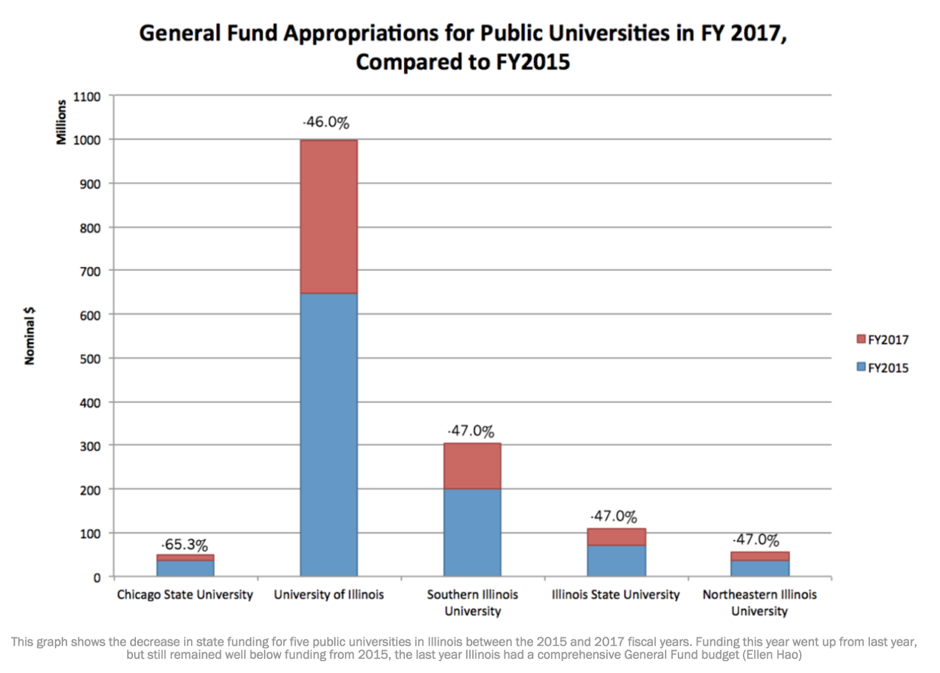

The Centre for Tax and Budget Accountability reported that the reduction in state funds had severely affected colleges like Chicago State University – Illinois’ only majority-minority university. State-appropriated grants comprise 32 percent of the university’s budget, yet in 2017 it saw the biggest reduction in its funding compared to other public universities in the state. This campus serves 3500 students, most of whom are African-American, low-income, and returning adults. Their worries were compounded when the Monetary Award Programs (MAP) ran dry, causing students to undertake more loans or refrain from enrolling all together.

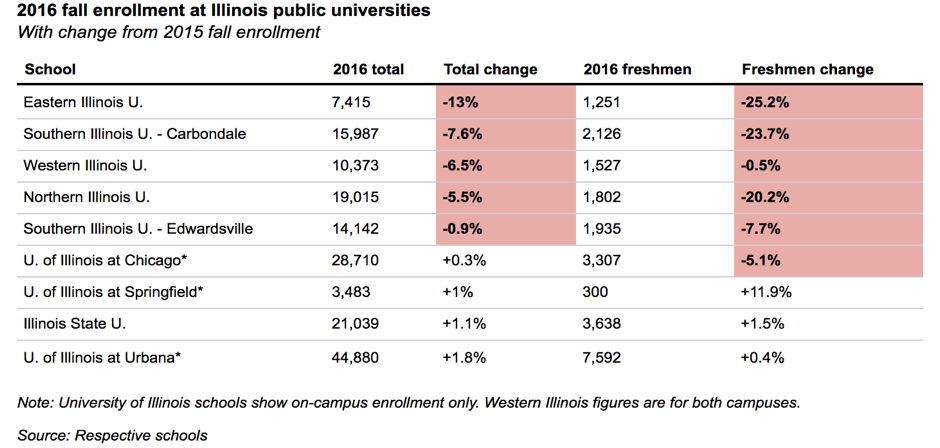

Other universities including Western and Southern Illinois were hit too, leading to draconian measures such as laying off employees, freezing hiring, cancelling classes, and eliminating student jobs.

Source: https://southsideweekly.com/budget-impasse-illinois-university-funding-bad-worse/

As is evident from the numbers below, the University of Illinois escaped relatively unscathed by engaging in a performance-driven deal with the government. While state funding only constituted 11.9 percent of the university system’s $5.64 billion operating budget in 2015, it comprised a critical portion of the $2.1 billion unrestricted funding that could be used to cover educational and administrative operations.

The deal required the university to cap the number of out-of-state students, increase its need-based financial aid, and limit the annual raise in tuition fees to the rate of inflation, all in exchange for state grants of the same amount as in 2015.

However, the contents of this deal drew criticism from two quarters that have nationwide implications.

Critics argue that the rules tying state spending to institutions’ performances such as graduation and freshman retention rates are unfairly disadvantageous to students who are not as well-prepared and less likely to graduate than their peers on flagship campuses. This adds an extra burden on schools like Chicago State University that have both a sizable minority population and a significant dependence on state grants. It also causes universities to be biased in their selection of students to ensure returns on these investments. 83 percent of Chicago State’s students are Black and Hispanic compared to 14 percent on University of Illinois’ Urbana campus.

On a related note, community colleges across the US enroll 52 percent of all African American and 57 percent of all Hispanic students in higher education, as reported by the Urban Institute. While the lack of government funding has hit regional universities and community colleges in Illinois, the steady decline of money spent on community college students nationwide makes them lesser of a safety net than they were intended to be.

In 37 states, students would have to work 20 hours a week or more at a minimum-paying job to attend these colleges full-time. A study in the Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis journal found that in Tennessee, public money was siphoned off to top public universities with more white and high-income students, leaving colleges with racial minorities and low-income individuals in the lurch.

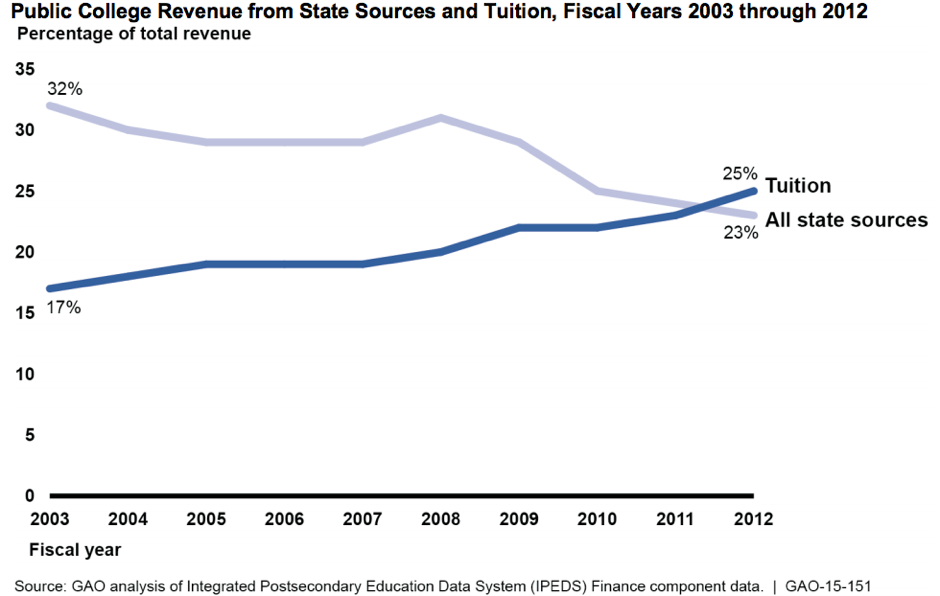

The second stream of criticism comes from the ongoing debate regarding limitations on the number of out-of-state students. Following the 2000s recession, there has been a significant decline in funding for higher education from state legislatures. In order to make up for the rising costs of providing education to an ever-increasing number of college-goers, universities rely on tuition revenue, thus shifting the burden onto students. With regulatory caps on in-state tuition, schools seek out-of-state students who, for example, in the case of the UC system, pay three times as much as Californians in fees.

Research examining the relationship between higher education and the level of nonresident enrollment at public institutions across the US from 2002-3 to 2012-13 found at least a 2.7 percent increase in out-of-state enrollment for a 10 percent decrease in state financial appropriations.

Meanwhile, closer to home, out-of-state tuition at the UCs helps keep the costs for Californians low and funds financial aid while simultaneously reducing the university’s dependence on state grants to avoid slumps during recessions. Though the number of such students accepted are lower than other state schools across the nation, the move has been highly criticized on two levels.

In-staters are wary of losing seats in their top campus choices and being turned away despite having high scores that meet the requirements. This lack of access to institutions that are funded by their parents’ tax dollars points to a more subtle issue.

Students who do not secure admission in campuses of their choice are referred to UC Merced, a school that has raised concerns of being disproportionately Latino and African American, causing a divide amongst popular campuses like UC Berkeley, Los Angeles, San Diego and less sought after ones like UC Riverside and Merced.

Thus, seemingly both the routes of dependence on state-appropriated funds or on out-of-state tuition to fund the growing cost of education are erroneous.

On one hand, universities lie more vulnerable to dips in economic activity and budgetary spending; on the other, in-state students feel unwelcome at colleges that pledge to serve them first. Further, both of these means of grant procurement widen the racial and socioeconomic divide that access to higher education ideally aims to bridge.

As recently as March 2017, the UC Board of Regents acted to limit nonresident undergraduate enrollment to 20 percent and increased its intake of Californian students by 5000 in return for $25 million in additional state money. Nonetheless, as the much-celebrated UC schools move towards striking a balance between two revenue sources, the Illinois higher education system proves a limiting case for schools seeking to rely on state appropriations to reduce tuition fees.

While the overarching question of why higher-ed costs are burgeoning remains, the state must be vigilant in its path to create a more equitable environment for all communities that could also robustly weather another recession.