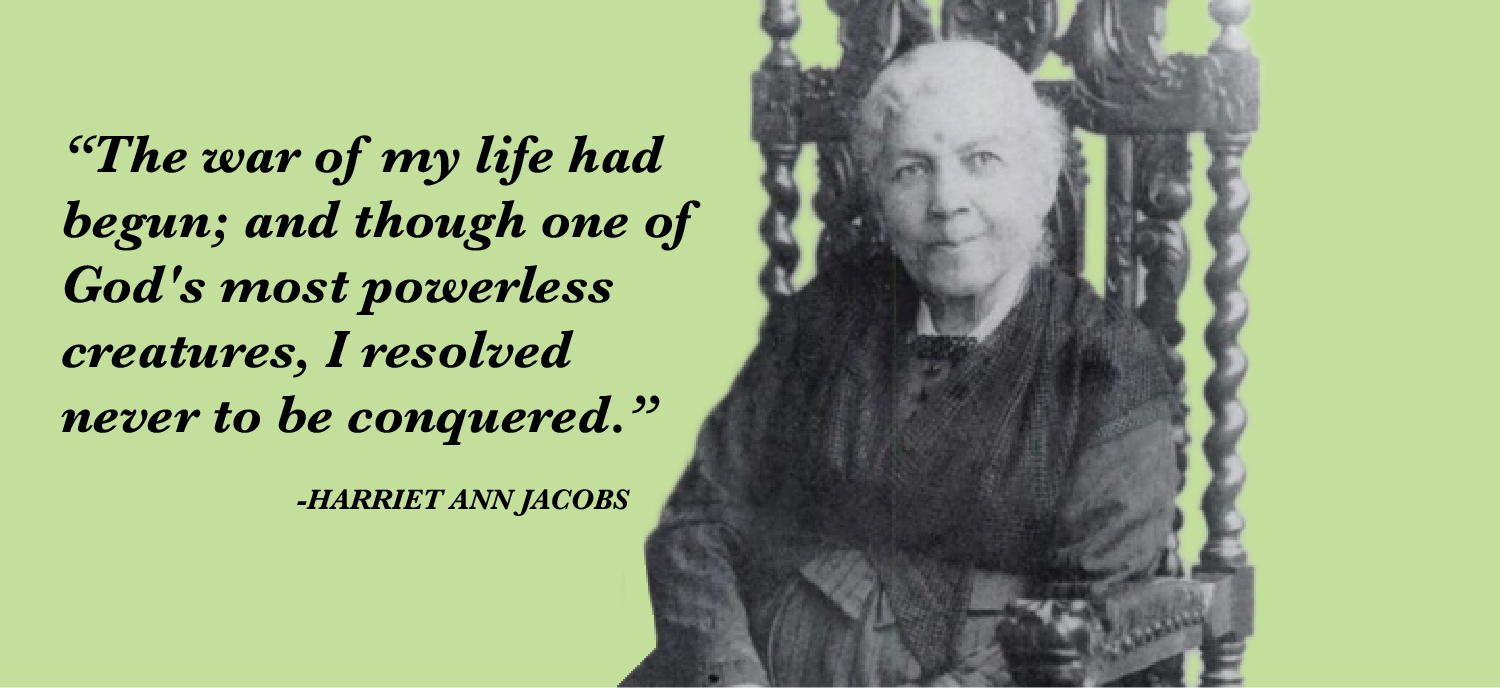

Harriet Jacobs: An Underrated Black Feminist

Design by Sara Haas, original photo in Public Domain via Wikimedia.

Prior to enrolling in Caroline Streeter’s “Trends in Black Intellectual Thought” course last quarter, I had never heard of Harriet Jacobs. In fact, most Americans, regardless of their educational background, would be slow to recognize her name. As I skimmed the course syllabus, my eyes hovered over her name: “Harriet, who?,” I asked myself.

Shortly after, I learned that Harriet Jacobs (1813-1897) was an African American woman born into slavery in North Carolina. Jacobs worked under various masters but was ultimately able to free herself from slavery, and went on to become an abolitionist and writer. As a writer, Jacobs centered her work on appealing to white women and northern abolitionists, hoping to expose the horrors of slavery from a non-white perspective. In the acclaimed “Incidents in the Life of A Slave Girl,” Jacobs explored the male and female slave dichotomy. This narrative, the first of its kind, demonstrates Jacobs’ personal experience as an enslaved woman in 19th century America. More importantly, “Incidents” celebrates the reclamation of one’s sexual agency as a highly unorthodox tool of both psychological and physical liberation. Because she refused to be confined to the “strong yet modest” archetype that black women can be confined to, Jacobs’ story has been relegated to the periphery of mainstream abolitionist history.

Due largely in part to respectability politics, other commendable black historical figures have replaced Jacobs in the average American history textbook, despite her status as the first woman to write and publish a full-length slave narrative. Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, for instance, are historically lauded as emblematic female slaves who significantly contributed to the abolitionist movement. Both women presented images of non-sexuality, bravery, humility, and a lack of formal education; such is the portrayal of the characterizing slave experience.

Additionally, Jacobs’ narrative has sparked controversy because it unapologetically highlights the triumph of an enslaved woman over society’s chains, rather than her demise at the hands of institutional racism and systemic oppression. Jacobs’ work is especially groundbreaking because it provides audiences with a fresh perspective on the slave narratives that have dominated the discourse for so long; in most slave narratives, which were written by men, women are unilaterally depicted as the helpless victims of white male abuse, which silences the diversity of their experiences. In contrast, Jacobs offered personal insight about the generally paradoxical and multifaceted role of black women in the American institution of slavery. In her abolitionist efforts, Jacobs explored how black women’s bodies were deemed disposable, and yet simultaneously economically and sexually necessary to white men. This topic was often deemed taboo among former slaves and white abolitionists because of its raw, “impious” truthfulness; in discussing the sexual abuse of female slaves, black women inadvertently relinquished their presumed “respectability” and “virtue.”

Although Jacobs acknowledged the horrors of slavery for men, she also argued that slavery “is far more terrible for women.” Her work emphasizes the multifaceted nature of the female slave experience, writing that “superadded to the burden common to all, [female slaves] have wrongs, and sufferings, and mortifications peculiarly their own.” The paradox thus lies in the intersectionality of the female slave’s identity, whose two main components, race and gender, subjected her to a unique experience. At the time, race rendered the black woman a slave, all the while her gender qualified her as the subject of sexual and reproductive exploitation. Jacobs’ powerful demonstration of sexual agency and impactful messages about gender-based violence and abuse have cemented her position as one of the most important black women in American history.