In Search of Pleasure: An Emotive Frame of Anaïs Nin’s Erotica

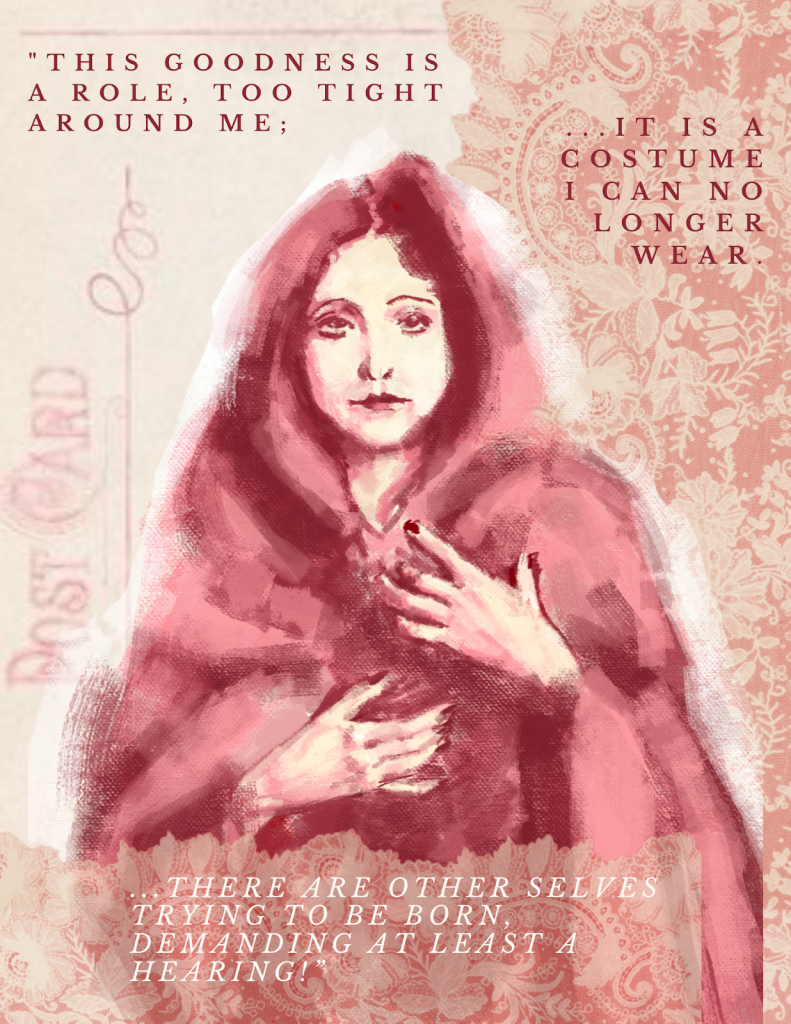

Image Description: Anaïs Nin stands with her hands holding a scarf around her body in front of a backdrop with shades of pink and white. The quote “This goodness is a role, too tight around me; it is a costume I can no longer wear. There are other selves trying to be born, demanding at least a hearing!” by Anaïs Nin, is surrounding her.

Sex is in the room today. I opened the door, and there it was, it filled every corner, it had spilled, and it made its mess. Sex is conversational, a series of moments leading up to a restoration. Sex can also feel like theft, it can force us to confront ourselves in ways we tend to ignore within the normalcy of mundane life. The act is gendered, it’s been categorized, it’s become mechanical and expectational. Sex follows women everywhere; what should be given is predetermined, the essence of sex has been stripped from women, it’s a phenomenon of objectification. Limits are imposed on women’s capacities to rekindle the innate relationship between themselves and true pleasure. Many might think pleasure should be without performance, and I can’t answer the question of whether performativity in sex is always harmful. Should it always be natural, completely fluid? There’s no black-and-white answer, however, there is a question to be posed about the constraints placed on women’s access to pleasure that is not performative, that is, without transactional properties. That being said, what kind of responsibilities should one consider when writing about sex? Are there specific margins to follow, and if so, how would these expectations fit between the lines of the subjective; how does the genre of erotica shape our conceptions of the world around us or our inner life? Anaïs Nin, diarist and novelist of the 20th century, catalyzed the genre of contemporary erotica, which flipped its primary consumers from men to men and women. Rather than simply shaping the preexisting genre of contemporary erotica, she spat on the male-dominated field and created her own:

Dear Collector: We hate you. Sex loses all its power and magic when it becomes explicit, mechanical, overdone, when it becomes a mechanistic obsession. It becomes a bore. You have taught us more than anyone I know how wrong it is not to mix it with emotion, hunger, desire, lust, whims, caprices, personal ties, deeper relationships that change its color, flavor, rhythms, intensities.

How should we express sex? For Nin, it is profoundly sentimental. Pleasure is not an isolated field of physical ecstasy, it is a fluid part of existence– it involves every part of us internally and externally. It cannot be limited to the whims of heterosexual male notions that go no further than complacency and passivity. Nin would have despised contemporary straight porn.

Nin’s work, which includes diaries and erotic short stories, is not limited in language nor consistent in theme. She is largely controversial, revealing notions of metaphorical incest in her writings about her father and the deep and often uncommon tie between sex and trauma. She also touches on infidelity, pain, sapphism, and other realms imaginable that could be promoted as intimately relative to sex. She is undiluted and admirable.

While Nin’s discussion of sex is certainly unprecedented, her motivation for doing so is particularly fascinating to me. In a 1974 radio show, Nin’s resentments toward the world and the difficulty of resonating with spaces and people are elucidated in the interview:

The few moments of communion with the world are worth the pain, for it is a world for others, an inheritance for others, a gift to others in the end, we also write to heighten our own awareness of life, we write to lure and enchant and console others. We write to serenade our lovers; we write to taste life twice, in the moment and in retrospection.

Emotion is spread throughout all of her stories. Nin nourishes works like Delta of Venus (a series of short stories) through the use of streams of consciousness which are also present within her diaries, allowing one to absorb the sexual connotations of explicit images along with the raw, emotional inner life of the narrator. The emotional aspect of sex has historically become conflated with a lack of power. To indulge in emotions during sex is to be weak because of its associations with femininity. Nin would think this is a deprivation of a fuller, more satiating pleasure. The dull societal image of women depicts their position in sex through two extremes: oscillating between being figurines of sexual pleasure, performance, the loss of the self, or the presentation of obedience, purity, and well-deserved, loving consummation. One is over-emotional, and the other is mechanical, it is numb.

Nin puts pen to paper and asserts all of the above is restrictive and blatantly unrealistic. When sex is deprived of its emotional characteristics, we assume it is inherently separate from what it truly is; we suck the life and fun out of it. To throw words like “casual” and “meaningless” next to sex as if sex with meaning is dangerous and weak; the era of so-called “casual sex” confuses our attempts to label the enjoyment of sex as normality and has conflated it with meaninglessness. Nin’s enthusiastic revival of the relationship between sex and emotions invites readers to analyze their own approach to their sex lives. The twitch that comes with believing desires are inherently intertwined with emotions, even if it’s only for a moment, becomes suddenly too daunting. For Nin, an ember becomes flame when we awaken the connection between our brains and our bodies during the act. Through streams of consciousness, Nin finds that by expression of thinking and feeling, one can make amends with their own thoughts, their own feelings of awkwardness, and the mystifying parts of sex that are hard to put words to.

Although the presence of sex is undeniable in her works, it is part of the essence of one’s life. It can even be the lack of sex in one’s life that is worth exploring, the disdain for it, the disconnection to it. She is not limited by the recreation of the act itself on the page; Nin creates a world of subjective experience, one where women can see themselves through Nin’s characters. They can recognize their own faces in a page that uncovers their own desire for a certain intimacy, or the lack of a need that they haven’t been able to reckon with. The unspoken ugliness of sex, the parts where we feel shame, the parts where it gets good. There is room for it all in her writing; she dug a hole in the cemented genre that it was before she stepped foot in the arena of erotica.

After all, Nin believes:

This goodness is a role, too tight around me; it is a costume I can no longer wear. There are other selves trying to be born, demanding at least a hearing!

Some Intimate Reading Recommendations:

A Spy in the House of Love

Delta of Venus

The Diary of Anais Nin Vol 4: 1944-1947

House of Incest