International Women’s Day’s Labor Movement History

Image by Robert Diedrichs via Wikimedia Commons

“A Day Without a Woman,” the women’s strike planned for International Women’s Day, is by nature a statement about the role of women in the international economy. When women abstain from work, society is forced to value women’s participation in not only the formal workplace but in the informal caring economy as well. In recognition of this, the organizers of the strike call on women to refuse to perform compensated and uncompensated labor, avoid shopping, and wear the color red because of its historical association with labor. Ashley Bohrer, a member of the strike’s national planning committee, maintains that the strike attempts to resist the past “decoupling of International Women’s Day from its very radical working-class background.”

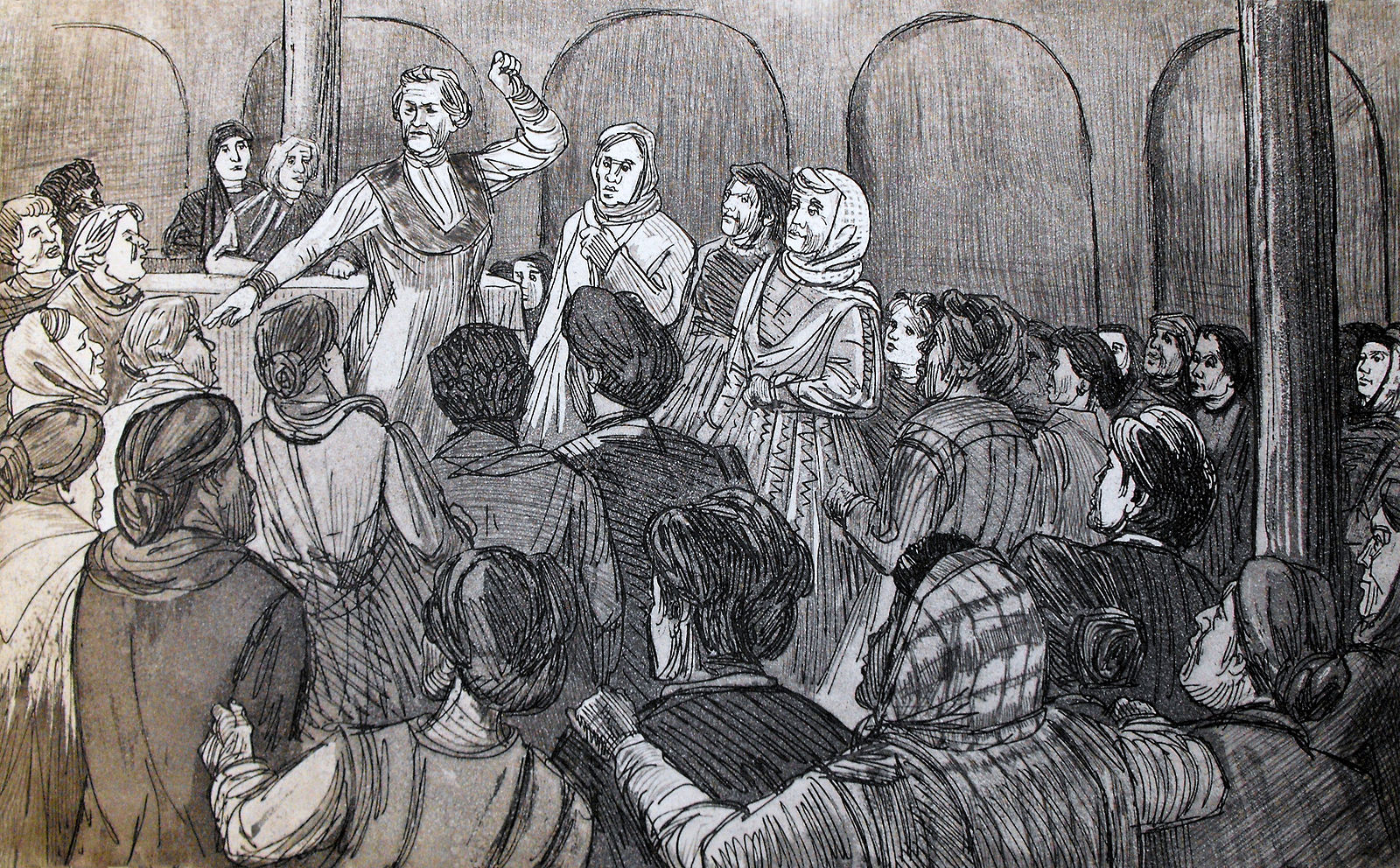

The celebration of International Women’s Day and labor politics are inextricably connected. The observance originates from the 1910 International Conference of Socialist Women in Copenhagen where German socialist leader Clara Zetkin demanded that, “in agreement with the class-conscious political and trade organizations of the proletariat in their country, socialist women of all nationalities have to organize a special Women’s Day”. No specific date was chosen. At the conference, women debated the issues of full suffrage versus qualified suffrage, the length of the working day for women, maternity insurance, 18-week maternity leave, the extension of maternity protections to unwed mothers, and even abortion in terms of “a review of the laws on infanticide, committed mainly by mothers who have been abandoned to their fate.”

In the article “On the Socialist Origins of International Women’s Day,” Temma Kaplan details the historical relationship between the holiday and labor. The first European celebration of International Women’s Day was held on the fortieth anniversary of the Paris Commune, March 18, 1911. Viennese women marched around the city carrying red flags in honor of those killed at the Paris Commune, and the Socialist delegates of the Austrian Parliament openly stated their support for women’s equality and suffrage for the first time that day. Americans celebrated the day on the last Sunday of February, the date declared by the American Socialists to be National Women’s Day in 1908, before the establishment of the international holiday. Russia observed the American date.

On the occasion of International Women’s Day 1917 (Feb. 23 on the Gregorian calendar but March 8 on the Julian calendar used in Russia at the time), working women in St. Petersburg led a demonstration against rising food prices and mass layoffs. Women working in textile mills went on strike alongside men in protest against WWI and the autocracy. Threatened by the continued unrest, Czar Nicholas II gave authority to the General of the St. Petersburg Military District to use lethal force if necessary to shut down the women’s revolution. These events marked the beginning of the February Revolution and established the current date for International Women’s Day.

Working with Clara Zetkin, Lenin declared International Women’s Day to be an official Soviet holiday in 1922. In 1949, the Chinese government would honor the holiday by giving a half-day off for women, a tradition still followed to this day. The holiday was celebrated primarily by socialist countries until the mid-seventies, when the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution announcing a “United Nations Day for Women’s Rights and International Peace to be observed on any day of the year by Member States, in accordance with their historical and national traditions.”

Today, International Women’s Day has become abstracted from its roots in the organization of women’s labor. The International Women’s Day website claims that the holiday “means different things to different people. For some it’s a celebration, for others it’s a call to action to accelerate gender parity, and for many it’s an opportunity to align and promote relevant activity.” None of these activities, it seems, include organized demands for better working conditions in women-dominated workplaces or the formal recognition of unpaid labor.

The International Women’s Day website encourages women to instead #BeBoldForChange and gives examples of “bold actions” including appointing a woman to a company board, buying from companies that support women, and learning to code. The scope of action against inequality is thus limited to celebrating and promoting the gains of individual women within a corporate workplace. Unsurprisingly, the site is partnered with companies such as BP, Pepsico, and Western Union that have a vested interest in preventing any kind of real, large scale women’s labor movement.

In today’s era of “lean-in” feminism and corporatization of diversity, the efforts to pivot International Women’s Day back to its origins in labor are refreshing. So if you can, take the day off work, and resist the depoliticization of March 8th!