On Being Asian American at UCLA, & in Today’s America

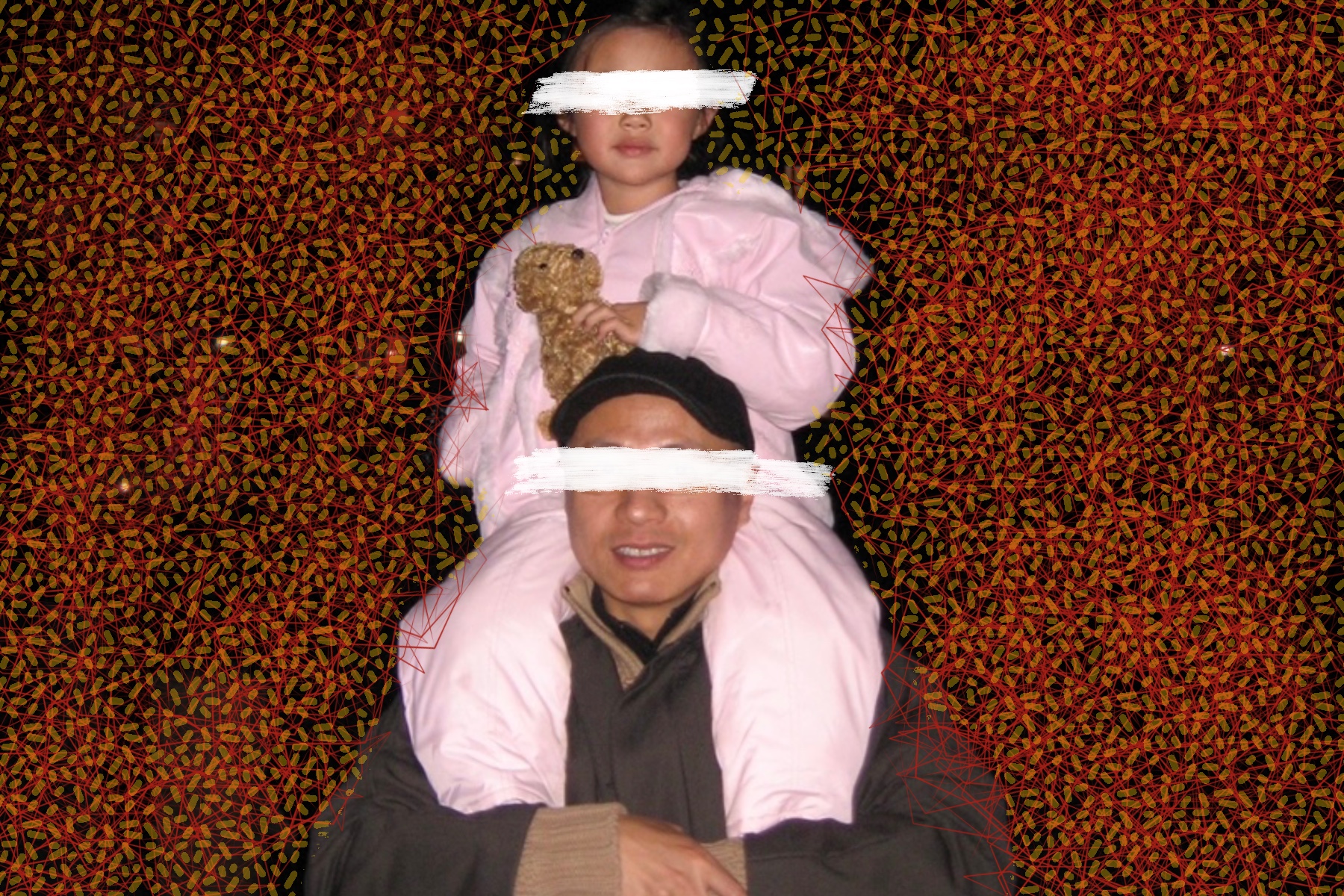

Design by Sarah Huang. Image Description: At the center of the image, a young Asian girl holding a teddy bear sits atop a man’s shoulders — their eyes are blocked out with white paint strokes. The background is made up of opaque yellow docs and overlapping red geometric shapes.

Content Warning: discussion of violence, harassment, racism, and sexual violence

On Feb. 9, 2022, UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center (AASC) received a flier in the mail proclaiming that a white supremacist rally was to be held on campus the following week. The flier included anti-Asian hate and sexist language, as well as slurs targeting the LGBTQ+ and Black communities. Most jarringly, it praised the gunman of the Atlanta spa shootings, which occurred just over a year ago in March 2021. Eight individuals were killed in Atlanta, among them six Asian women, evidence of the increasing violence Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA) communities — especially women and elderly individuals — have endured since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. While our communities have always faced racism in America, the hate flier and other incidents prove that in many instances, anti-Asian violence continues to hit close to home.

The flier incident also sheds light upon a terrifying pattern of systemic racism for UCLA and greater Los Angeles’s APIDA community. AASC received a similar hate flier back in 2014. Last year, just minutes away from campus, an Asian woman was verbally harassed by a white man in Brentwood. An LAPD report from last year detailed how the number of anti-APIDA hate crimes in Los Angeles had more than doubled between 2019 and 2020, and just this past January, alumna Michelle Go (‘02) was killed when she was shoved in front of an oncoming subway in New York City.

The white supremacist rally that was alleged to take place on campus on Feb. 14 never occurred, but this incident — in conjuction with many others — begs us to explore the question: how did we get here, and what does it mean to be part of the APIDA community at UCLA and in today’s America?

A Brief History

While awareness surrounding anti-Asian racism has grown as the pandemic has persisted, contemporary instances are only one blip in a long history of violence. In the 1871 Chinese Massacre, which occurred right here in Los Angeles, a mob attacked Chinatown and killed 18 Chinese residents. This violence, along with the passage of the Page Exclusion Act of 1875 and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, represented growing anti-Chinese and anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States. The Page Exclusion Act in particular, which specifically restricted the arrival of Chinese women, highlighted how race and gender interact in producing a unique lived experience. Asian women were perceived as threats, effectively sexualized and reduced to objects of fetishization, deemed unworthy of ever becoming American. Chinese American families were separated as a result, and a precedent of APIDA exclusion was set in the United States.

The 20th century brought about even more anti-Asian violence, extending harm to even more APIDA communities. The attack on Pearl Harbor led to the forced internment and abuse of over 120,000 Japanese Americans on the West Coast, a majority of which were U.S. citizens. Southeast Asian refugees faced immense amounts of violence and discrimination at the hands of Ku Klux Klan members in Texas in the wake of the Vietnam War. Since the 9/11 attacks, South Asians communities, especially Sikhs and Muslims, have been victims of pervasive religious and racial hate.

When we look back at the history of anti-APIDA violence in the United States, it is unsurprising that we are currently experiencing an increase in violence along with the pandemic. APIDA communities have been scapegoated in times of national turmoil for almost as long as this country has existed.

The Model Minority Myth

Aside from a paragraph or two in U.S. history textbooks, why do we rarely reflect on anti-Asian hate incidents? The key culprit is the model minority myth, which characterizes Asian Americans as polite, submissive, and the perfect minority group. It asserts that somehow, through sheer grit and innate talent, we have persevered even as “foreigners” in this country. We are praised for always being able to achieve a high level of success — after all, if we can do it, who’s to say other people of color cannot?

The model minority myth is extremely problematic for a variety of reasons. First, it erases both the historical and contemporary racism Asian Americans have experienced. It suggests that America has always been a welcoming place for us, one where we have always been promised the opportunity to fulfill our American Dreams.

But that brings us to yet another issue with the model minority myth: it reduces Asian Americans to a monolith. It takes away from the vast diversity of the cultures, people, and stories that make up the APIDA community by lumping us into one stereotypical experience. It leads to the assumption that all Asians earn higher degrees and bring in larger incomes when in reality, there are stark differences between different APIDA communities. Less than 20% of Bhutanese, Laotian, Cambodian, and Hmong Americans earn Bachelor’s Degrees, a rate significantly lower than the APIDA average of 50%. In contrast, 75% of Taiwanese Americans earned college degrees. Similarly, the poverty rate ranges from 7% for Filipino Americans to 39% for Burmese Americans, a number almost quadruple that of the average percentage of APIDA and white people who live in poverty.

When we disaggregate even just the numbers, it becomes increasingly clear that lumping all Asian Americans together into one stereotypical experience is not only inaccurate, but also harmful. South, Southeast, West, and Central Asians deserve to have their perspectives honored just as much as East Asians, but all too often their identity-specific struggles are erased.

Unfortunately, the model minority myth still effectively bars many of these APIDA communities from receiving the specific support and resources they need to address deep-rooted systemic inequities.

Finally, the model minority myth is detrimental because it pits marginalized communities against each other, ultimately playing a role in perpetuating anti-Blackness within and outside of APIDA communities. It pushes for other racial and ethnic groups to overcome hardships and achieve the same “success,” downplaying the trauma, racism, and discrimination Black people especially have faced in this country. By pitting people of color against each other, the model minority myth also effectively hinders the collective fight for racial justice.

Being Asian American at UCLA, and in Today’s America

So how does all this — a history of violence, the model minority myth, recent incidents at UCLA and across the nation — shape our lived experiences as Asian Americans today?

While I can only speak to my own experience, others in the APIDA community may resonate with me when I say that I feel a multitude of emotions. Growing up in a predominantly white community where the model minority myth was pervasive, I harbored an immense amount of internalized racism and was ashamed of my identity for a long time. I once fully believed in the stereotypes perpetuated by the model minority myth and as a result, felt a strange mix of both inadequate and proud when I couldn’t embody them.

However, today I feel incredibly proud of my racial and cultural identity. When I reflect back on the years since I’ve left my hometown, I attribute much of my growth to being here at UCLA, where I am surrounded by so many wonderful APIDA students who share similar backgrounds. Each day, I am inspired by UCLA students who are proud of their identities and graciously share aspects of their cultures with the rest of campus — students who, day in and day out, fight for the visibility of their APIDA communities.

It is also especially crucial to avoid falling into the model minority trap at UCLA. This first entails recognizing that Asian American students on campus cannot be reduced to a monolith; Hmong students may have different experiences at UCLA compared to Korean students, Pacific Islander students, or Indian students. It is essential that we acknowledge the diverse socioeconomic and educational backgrounds our APIDA student communities come from in order to best support those with unmet needs on campus. Additionally, while APIDA students make up a large portion of our student body, this doesn’t discount the fact that many of us have faced racism at UCLA or other institutions. As evidenced by recent incidents, there is still the pressing need to invest in dismantling anti-Asian violence.

Amidst our own grief and healing, there is also the need for APIDA communities to confront the anti-Blackness that is unfortunately prevalent in our circles. Many of us, especially our beloved immigrants who have persisted in this country despite violence, have internalized the model minority myth and in turn completely disregarded the discrimination Black people have faced in America. Thus, moving forward for us entails investing in community organizations, education, and restorative justice initiatives instead of pushing for increased law enforcement. It entails joining forces with our Black, Indigenous, and Latinx allies to reimagine justice and promote anti-racism for all communities, at UCLA and beyond.

Another part of me feels helpless. The hate flier incident right here at UCLA serves as a painful reminder that even in community spaces deemed safe by many of us, anti-Asian violence is still present. Other recent occurrences have had the same effect — from the spas in Atlanta, to our beloved Chinatowns in New York City and San Francisco, to the immigrant-owned small businesses we cherish — it feels as though our safe spaces are being stolen from us. These incidents highlight how the most vulnerable members of our communities face a violence that is uniquely tied to our intersectional identities. It is a violence in which America’s longstanding history of racism, misogyny, and imperialism intertwine and directly impact the everyday lives of many.

Above all, I also feel a prevailing sense of hope. I feel hopeful for the APIDA community, one that is full of proud immigrants and selfless leaders and wise voices; a community that has come together in the past few years in collective mourning and healing. I feel hopeful that we can invest in community resources and shape a reimagined future of justice with Black, Indigenous, and Latinx communities by our sides. Above all else, I feel hopeful that one day we will be able to call our beloved spaces safe again — from UCLA’s AASC, to our small businesses, to the cities we love, and everything in between. In a country that has always viewed us as foreigners, future APIDA generations deserve to have spaces and communities to call home.

The upcoming month of May is National Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

APIDA organizations and resources in the Los Angeles area can be found here.

APIDA mental health resources, including therapist search assistance and community events, can be found here.To find and join some of UCLA’s phenomenal APIDA communities, see here.