Race, Identity, and Invisibility in the American Novel

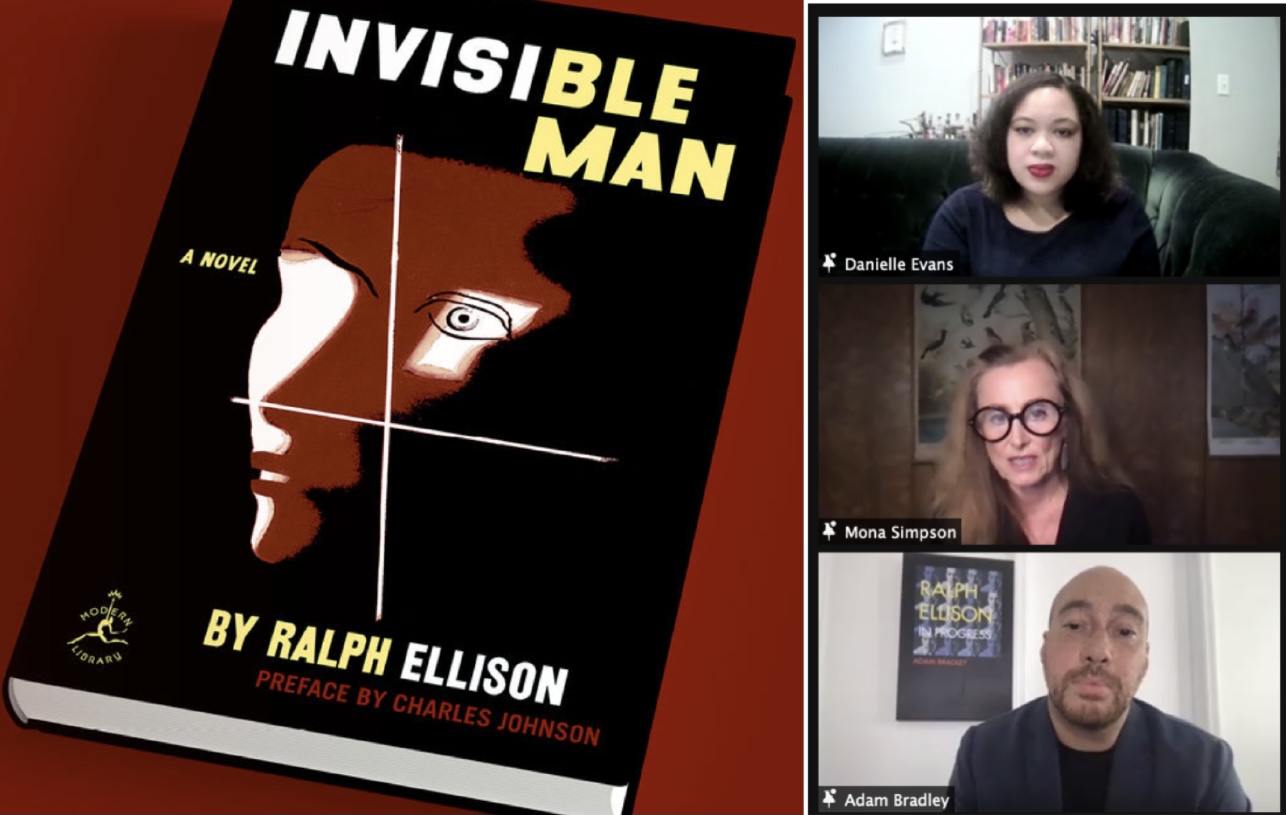

Image Description: A photo of the book Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison alongside zoom boxes with three speakers: Danielle Evans (top right), Mona Simpson (middle right), and Adam Bradley (bottom right).

Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man was published in 1952, but remains relevant in 2021. UCLA’s Hammer Museum brought together an esteemed group of scholars and writers to highlight exactly this. The novel tells the story of an unnamed narrator’s journey growing up in a Black community in the South, attending university and getting expelled, and leading a group called “The Brotherhood” in Harlem, New York City. It addresses many challenges Black people faced in the early 20th century, raising questions of nationalism, personal identity, and individualism.

Over four weeks, the Hammer Museum hosted three virtual seminars and a final panel, all of which were open to the public, to discuss and revisit the themes, structure, voicing, and politics of Invisible Man. Held on May 18, 2021, the final panel tied together prior discussions and explored the aspects of Invisible Man that are connected to the current political moment. The panelists also discussed the novel through an intersectional lens, specifically focusing on the narrator’s identity and its ties to invisibility in the U.S.

The discussion was moderated by Mona Simpson, an esteemed novelist and UCLA English professor. Simpson was joined by author and John Hopkins professor Danielle Evans, as well as Adam Bradley, a UCLA English professor, founding director of the Laboratory for Race and Popular Culture (the RAP Lab) at UCLA, and biographer of Ellison. Evans began the conversation with a reading of a powerful excerpt from near the end of the novel, where the narrator witnesses a fellow Brotherhood leader getting shot by a policeman. The excerpt sparked a conversation about how Invisible Man makes references to history — slavery and the Great Migration are heavily referenced throughout — but also presents scenes that reflect the U.S. today. Evans also brought up the symbol of the briefcase, which represents the narrator’s literal and figurative “baggage,” as he carries with him the history of his race and identity.

The panelists then discussed the ideas of invisibility that are brought up in Invisible Man on a broader scale. Bradley and Evans stressed that one of the biggest takeaways from the novel is understanding where you fit in as part of a community. The narrator’s invisibility forces us to reflect on our personal identities, and acknowledge how many communities and their cultures and histories are systemically set up to be invisible in the U.S. The novel also encourages us to recognize that instead of embracing the invisibility, as the narrator does initially because he wants to defy stereotypes, one should take steps to overcome it. In the end, he is determined to make an impact outside of society’s prescribed roles, urging readers to do the same.

While this is a powerful and inspiring message because the notion of invisibility is still incredibly relevant to many communities today, keeping intersectionality in mind is important. Overcoming one’s invisibility is much easier said than done, especially because it is systemically rooted. Additionally, individuals may harbor other identities that make simply prevailing over their invisibility virtually impossible. The panelists discussed how Invisible Man’s dialogue surrounding intersectionality is lacking, as it fails to shed light on the different types of invisibility people can encounter as a result of their marginalized identities. Evans specifically pointed out that the female characters in the novel are not as complex or developed, something she is sure to point out when teaching Invisible Man to her students.

Nonetheless, Ellison’s work serves as a haunting reminder of the challenges Black people in the U.S. face, relevant both at the time of publication and today. At the end of the discussion, Bradley mentioned that soon after publication, Ellison did not believe it would be applicable in 25 years because he assumed the issues surrounding Black identity throughout the novel would be resolved. Evidently, this was not the case. Invisible Man’s continued relevance demands our attention, labor, and discourse, but it also serves as an opportunity for readers to personally connect with the narrator’s struggles. The final line, “Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?” demonstrates Ellison’s intention of universality and inspiring readers to grapple with — and most importantly, embrace — their own identities.

A recording of the panel discussion can be found on the Hammer Museum channel here.