The Future of Disability Studies: Afrofuturism, Literary Criticism, and the Intersection of Blackness and Disability

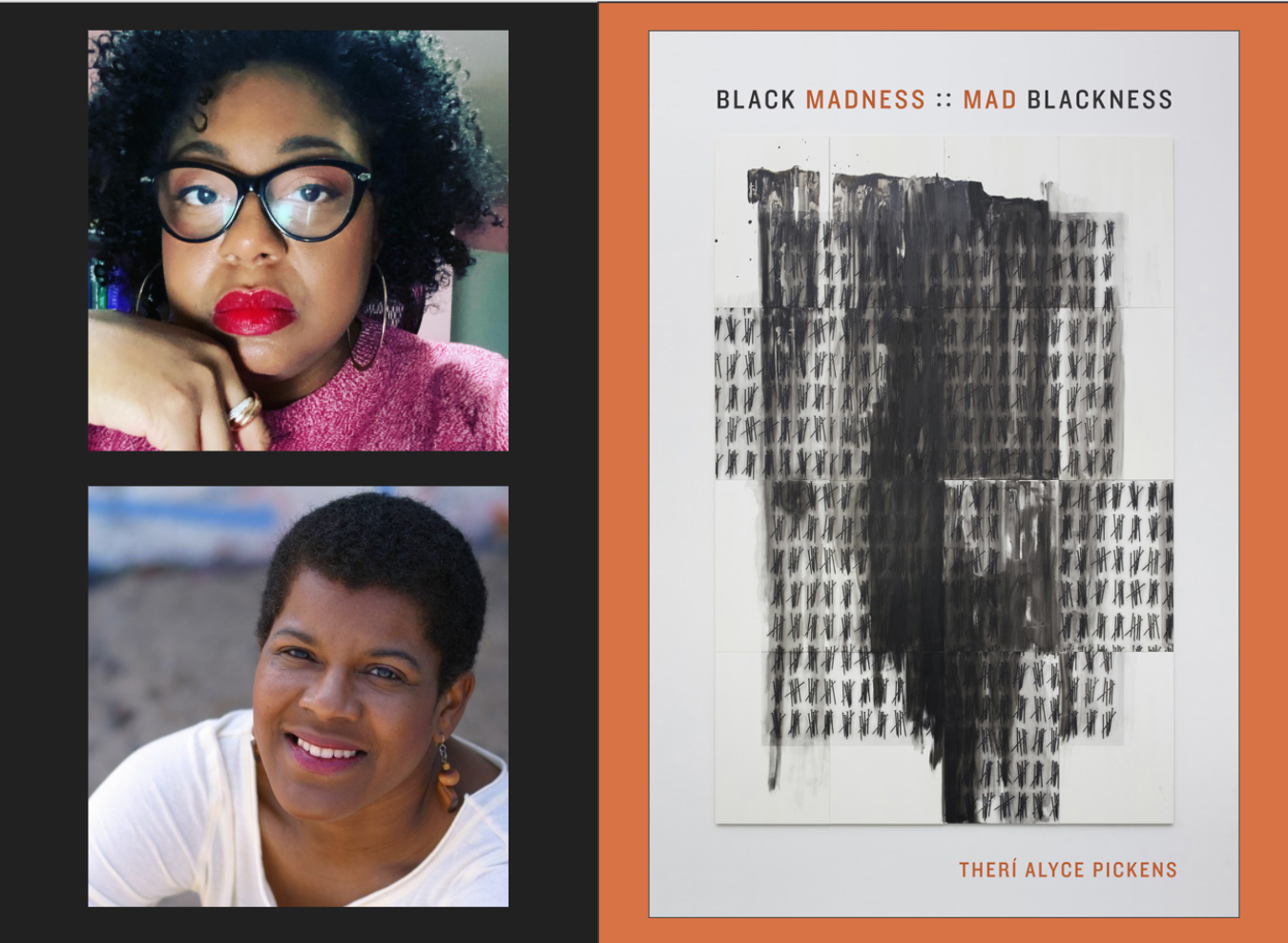

Image Description: The upper left of this graphic features a photo of Therí Pickens, one of the speakers in this event, staring seriously at the camera while wearing black glasses and bright red lipstick. In the lower left photo, Tananarive Due, another speaker, smiles at the camera. The right side of this graphic depicts the cover of Pickens’s new book, Black Madness: Mad Blackness, against an orange background.

On April 13, UCLA’s disability studies department hosted a webinar entitled “Conversation with Therí Pickens, Tananarive Due, and Juliann Anesi,” which punctuated a series spanning four months called “The Future of Disability Studies.” The event was moderated by Anesi, but Pickens and Due led the main conversations surrounding Afrofuturism, a sub-genre of science fiction that centers Black people and culture, or, as Pickens stated, an “aesthetic, social movement, political movement, [and] set of theories.” They also discussed literary criticism and the overall intersection between Blackness and disability.

Tanarive Due is a Black horror and Afrofuturist professor at UCLA, as well as an award-winning author of over 20 books within these genres, including The Black Rose, My Soul to Keep, and The Between. Additionally, she was the executive producer of a Shudder documentary entitled Horror Noir: A History of Black Horror.

Therí Pickens is a professor of English at Bates College, where she specializes in African American, Arab American, and disability literature and theories. She shared insights on her second book, Black Madness: Mad Blackness, which was published in 2019. A Black disabled woman herself, Pickens explained that this book attempts to “disrupt the idea that Blackness and madness are somehow equal.” Pickens maps the intersections of Blackness and madness by referencing Due’s fiction, as well as the works of other Afrofuturist authors such as Octavia Butler and Nalo Hopkinson.

When asked to speak on the title of her book and define “Black madness” and “mad Blackness,” Pickens pointed out that she is certainly not the first scholar to write about these concepts. With her title, Pickens aims to pick apart the many connotations of the word “madness” — while this word usually means mentally ill or cognitively impaired in the context of disability studies, it can also mean “angry” or simply “very.” She also aims to subvert readers’ expectations while reading the title, because the phrase that comes after the colon does not provide more explanation (which is often the case for academic texts). Rather, the title forces academics to take a beat to think about the title and essentially create their own definition of these phrases.

Next, the pair discussed the role of Afrofuturism in the book. Pickens claimed that she used this genre as a starting point for her book because it is a “prime place from which I might understand a world that is aggressively against the enlightenment sensibilities about what it means to be human.” From there, she was able to mix literary criticism with her own ruminations on the role of disability in these texts. Pickens further explained that Afrofuturism allows for us to privilege Black folks at the center — a practice that is rare unless they are the center of controversy.

Due gave insights as a Black speculative fiction author herself. Texts in this genre effectively combat white supremacy because their authors often have personal and inter-generational traumas that directly result from this racist ideology — an experience that Due is all too familiar with. During a 1960s protest, a police officer threw a tear gas container at Due’s mother upon recognizing her as a leader of the student movement at her school. She was only 20 years old at the time, but afterward, she experienced extreme sensitivity to light and had to wear dark sunglasses about 80% of the time, even while indoors. This cop’s racist assault physically prevented Due from looking her mother in the eyes for the majority of her life. She channels this sense of loss and horror in her work.

Pickens hopes to leave readers with several key lessons after reading Black Madness: Mad Blackness. First, when it comes to Black literature and disability, she stated that “it’s okay for it to be complicated” — authors don’t have to strive to create an impossibly neat resolution to these impossibly complex problems. Additionally, Pickens hopes to leave readers with a chronicle of Black folks in speculative fiction. She recognizes that many people have already written about Toni Morrison and hopes to highlight the work of other amazing Black authors in her book. As Pickens aptly put it, “There’s a wealth of knowledge and wisdom in artists.” Pickens and Due’s thoughtful conversation certainly prove this statement to be true. The future of disability studies is in good hands.