The Ongoing Battle for Recognition and Reparations for Comfort Women

Content Warning

To this day, not many people are aware of the mass exploitation of women by the Imperial Japanese Army that occurred during World War II. This period of military sexual slavery of 200,000 women was an example of a massive human rights abuse, organized on an unprecedented industrial scale. The worst part is: these 200,000 women have never received a formal apology.

Many have since passed away, but the ones who still live are around age 87. Serving as their own advocates, they fight for an official apology and legal reparations for horrors done to them because the memories still resonate too painfully to be ignored. The first rally in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, Korea was held in 1992, demanding compensation and recognition. These rallies have continued for 23 years; sometimes the women are joined by large crowds of supporters.

In addition to the women themselves who are fighting for legal justice, others have chosen to address the issue of ‘comfort women’ using art forms. Chang-Jin Lee is a Korean-born visual artist who lives in NYC. In 2013, she completed a multimedia project that serves to honor the memory and bring awareness to the plight of the females who were used as sex slaves during World War II, commonly referred to as “comfort women.” The term “comfort women” is used extensively in Lee’s project to represent the actual advertisements in newspapers for comfort women during that time. Lee’s complete project includes ad-like billboards, phone booth posters, and prints, which have all been featured in exhibits, galleries, and museums in Korea, Germany, Russia, Hong Kong, and the United States.

However, it is my opinion that the pinnacle of Lee’s project is her short video, a shortened version of which is available online here. In the video, you can hear the testimonies and memories of Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, Indonesian, Filipino, and Dutch “comfort women” survivors, and a former Japanese soldier firsthand. Previous films such as “Silence Broken,” are also commendable works, and have mostly chosen to focus on Korean comfort women, largely because they were the majority. However, Lee’s video is truly unique because it really showcases many survivors voices, allowing them to each tell their stories uninterrupted, with only subtitles and their black and white image on the screen. Thus, you can really feel the pain, sadness, grief, and sometimes pride in each woman’s voice, and each story cuts through you like a knife to the heart. So far, both Asian and European women have come forward to tell their stories. The youngest were 11-years old, and the oldest was 27. Most were either lured by false promises of a job as a nurse, or simply kidnapped from their homes outright. In the video, you can hear some lament that they were seen as “just women,” or worse, “just Asian women.” Below are some of the personal testimonies that Chiang Jin-Lee has gathered.

Testimonies

Emah Kastimah, an 81-year old Indonesian survivor, remembers: “This was not work. This was assault. If I refused, I was beaten. It hurt my heart. My mother died during that time and I didn’t even know what happened to her.”

Some, like Lian-Hua Chen, an 89-year old Taiwanese survivor, remember everything in chilling detail. Chen was sent to a Japanese comfort station in the Philippines, where she and the other girls were given Japanese names and kimonos to wear. The only time they ever saw each other again was when they went for weekly medical exams. Otherwise, they suffered in silence alone. When the war was finally over, the soldiers took the group of girls and fled into the mountains, hiding there for a whole year because they feared facing Allied retribution. When they finally decided to come down, the girls were free to start new lives; some eventually met husbands or went back to school. Because of her grueling work as a “comfort woman,” Chen was not able to have children, but was able to adopt.

Fedencia David, a Filipino survivor, recalls how she was taken from her village at age 14, along with her grandmother. Both women were suspected of being part of the guerilla movement, even though this was untrue. After her ordeal, David recalls her psychological trauma: “I was out of my mind, crying and laughing at odd moments.”

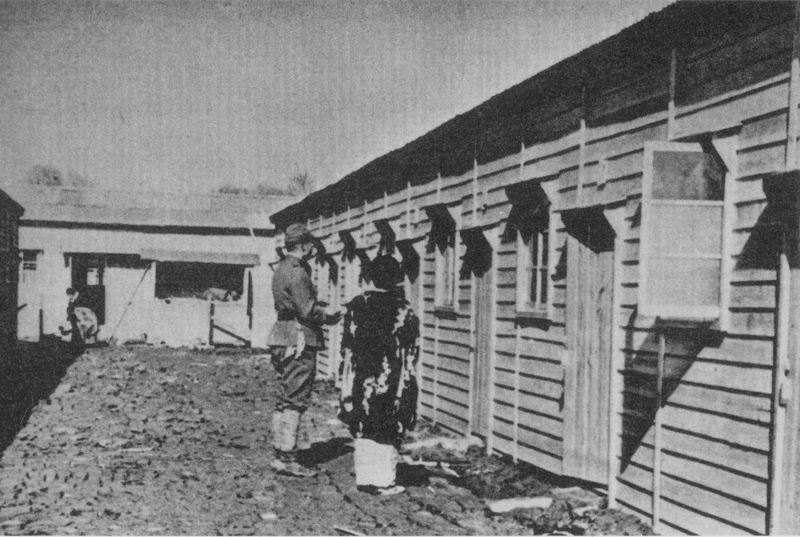

Oak Seon Lee, a Korean survivor, was kidnapped along with several other girls, on the streets of her village. Instead of being able to go to school like she so desperately wanted, she was sent via boat to a forced labor camp in China on July 29, 1942, with no food or water. She recalls that the camp had about 100 boys and girls, all under age 20. They were fenced in with electrified barbed wire and overseen by guards with guns. She was sent to a comfort station because she was too rebellious, too loud. There, she was told that she had to ‘repay the Japanese’ if she ever wanted to return home. She recalls seeing girls only 11-years old, girls cut deeply with knives for sport, girls having babies there. Lee had her uterus taken out. She also recalls: “If you collapsed, the soldiers left you there to die.” When the war was over and the Japanese finally deserted the camp, all the girls were able to run away, even though they were starving and did not know where to go from there.

Aihuwa Wan was the leader of the Chinese Communist Party. The Japanese caught her and tortured her in order to obtain the list of Party members. She served as a child bride and as a “comfort woman.” In the 1990’s, she was the first Chinese woman to speak out publicly about her ordeal. Afterwards, she went to the Japanese court seven times, each time failing to prosecute those who ran the comfort stations. “I have waited for decades,” she says.

Now

In terms of compensation, there have been several personal apologies to former “comfort women” from ex-prime ministers, and an admission by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs that some women working in brothels overseen by the government were “deprived of their freedom.” However, in 2007, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe denied that the Japanese ever kept sex slaves, or forced women into sexual slavery during World War II. Even after he apologized for this statement, many nationalists still maintain that the comfort women went of their own free will. In addition, controversy continues over the wording, degree of formality, and presentation of the apology. The Abe Administration has faced pressure from many, including cabinet minister Inada Tomomi, to “restore Japan’s honor” by rewriting or withdrawing the existing Kono statement. (The Kono statement recognized the coercion used by the Japanese government, but was a long way from apologizing or giving monetary or legal compensation.) More recently, California Congressman Mike Honda passed Resolution 121 in 2007, which asked that the Japanese government formally apologize to former comfort women and include curriculum about them in Japanese schools. Sadly, conservative Japanese groups and politicians, like the Mayor of Osaka Toru Hashimoto, have sprung up to oppose such legislation and even basic recognition of the comfort women and their experiences. Mayor Hashimoto still maintains that “the use of comfort women was necessary, so that Japanese soldiers could have a rest.”

Even more recently, in Glendale, California, a bronze memorial statue was recently erected in a city park, which depicted a young girl in Korean dress sitting next to an empty chair, in homage to all of the comfort women. Immediately, some 300 legislators from around Japan sent a petition to Glendale, calling for the removal of the statue, and a conference in Tokyo claimed the statue was “spreading false propoganda.” Several nonprofit groups, such as the GAHT-US Corps, are also known for their staunch but unsuccessful legal attempts to block and then remove the statue. However, a federal judge ruled in favor of the statue and the awareness campaigns. At the statue’s unveiling, even though groups may have turned out to protest it (which is both disgraceful and disrespectful of the victims), still others laid flowers and gifts at its feet.

Current denial of events does not serve to dilute the past; it only inflames it. Despite denial from the administration, and the continued fight for justice, some have begun to come around. In the words of Yasuji Kaneko, a former Japanese soldier interviewed by Chang-Jin Lee: “My hope is that people will never repeat what we did in the war.”