The Other Woman

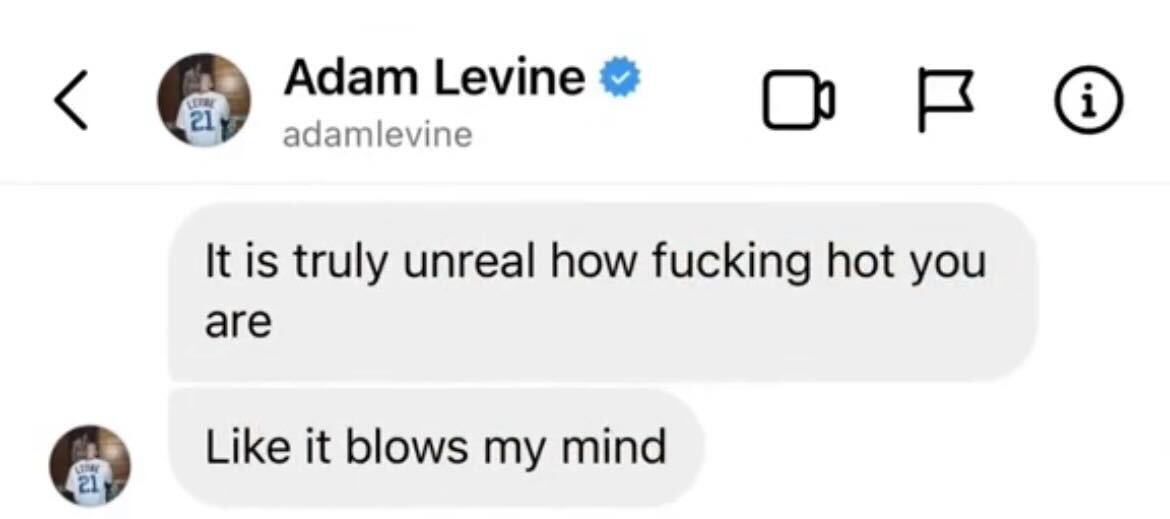

Image description: A screenshot of one of the Instagram DMs that Adam Levine (@adamlevine) sent to Sumner Stroh (@sumnerstroh) reads, “It is truly unreal how fucking hot you are. Like it blows my mind.”

Image credits: @sumnerstroh on TikTok

Whenever I get into a relationship — or at least get close enough to being in one — I’ve always found myself worrying about the guy cheating on me with someone hotter. Yes, it’s very superficial and insecure of me to think about relationships through the lens of physical appearance, but I’ve always found the idea of the “other woman” unnerving. Historically, the mythos surrounding the “other woman” illustrates her as a powerful temptress with extraordinary beauty that has the ability to overpower love & commitment. So whenever I’m in a relationship, I always assume that if I were to be cheated on, the “other woman” would have to be someone prettier than me, someone with more to offer, because otherwise, what’s it all for?

This notion of a femme fatale figure ruining stable relationships has become so deeply embedded within modern pop culture that we rarely expect beautiful women to be cheated on. We see this mindset reflected in our collective reaction to celebrity relationship scandals — see Ned Fulmer, John Mulaney, Sebastian Bear-McClard, and Adam Levine (the memes are getting out of hand). When we found out that even some of society’s most attractive were getting cheated on, it threw us for a loop. After all, how can the “other woman” be hotter and more seductive if the woman that’s getting cheated on is scientifically proven to be the “most beautiful woman on the planet” (Bella Hadid) or one of the sexiest women in the world (Emily Ratajkowski)?

But in reality, the preconception that hot women are immune to getting cheated on is shallow and completely untrue. Actually, the connection that we form between beauty and betrayal is totally arbitrary: it’s only sustained by the misogynistic idea that a woman’s worth and success are based on her looks. In fact, a study conducted by the Pew Research Center found that 35% of the 5,000 participants surveyed believed that physical attractiveness was what society valued most in women. But when it came to what the participants believed was valued most in men, 33% said honesty and morality, and physical attractiveness was mentioned by a mere 11%.

This association, however stupid and unfounded, has profound impacts on the way that we treat women today. The significance that modern society places on women’s looks suggests that a woman who is conventionally attractive is at the top of the hierarchy and therefore undeserving of and invincible to being cheated on. With this perspective, a woman’s appearance is the key determinant of her relationship’s success.

Now, translate this misogynistic bias to social media, a realm where anyone can leave anonymous comments wherever they like about whatever they like. When coupled with the occurrence of celebrity scandals, media platforms morph into an explosive crossroads in which virulently misogynistic discourse and conflict can rapidly emerge.

When news broke that Adam Levine cheated on his wife of 8 years, and former Victoria’s Secret angel, Behati Prinsloo in early September 2022, the comment sections of the “other woman’s” TikTok and Instagram posts transformed into an arena of vicious, biting contempt. Model and influencer Sumner Stroh had posted a TikTok on Sept. 19 — a mere five days after Prinsloo announced the pregnancy of her and Levine’s third child. In the video, Stroh details her illicit affair with Levine, stating that she felt “exploited” and “manipulated” due to the age difference and her unfamiliarity with LA & the modeling industry at the time. She revealed that after the affair ended, Levine reached out months later over Instagram DM to ask Stroh if he could name his third child after her, and she provided a screen recording confirming that the messages were real. Stroh’s video now has 26.1 million views and nearly 2 million likes. Shortly after Stroh’s public declaration, three other women came forward, confirming that Levine had also sent them inappropriate DMs while married to Prinsloo. In response, Levine released a statement on Instagram denying the affair but expressing regret over his “poor judgment” and pledging to work on fixing things with his family.

The scandal inspired many TikToks with something along the lines of, “It’s not about what you look like, all of these girls got cheated on,” with a slideshow of gorgeous celebrities. There were also edits of Behati’s runway walks as to say, “This literal supermodel got cheated on, so no one is safe!” The implications of these videos epitomize the subjective association we draw between beauty and infidelity, as well as how shocked many were that this association didn’t always hold true. In a sense, the allegations made about Levine were a staggering wake-up call that forced us to question our collective internalized misogyny regarding beauty and relationships.

In fact, Adam Levine’s scandal perfectly demonstrates how the entire concept of “the other woman” is inundated with casual misogyny. Sumner’s TikTok triggered a flurry of hate: people left (and are still occasionally leaving) scathing comments on her posts, blaming her for the affair. A couple left on the original TikTok include: “You’re only sorry because you got caught,” and “Levine went from Gucci to Dollar General.” From her most recent Instagram post captioned “heeeeey how y’all doin,” strangers reply: “Not homewrecking wbu” and “We are all great! Considering we aren’t trying to be side pieces.” Some comments simply resort to attacking Stroh: “Isn’t she trashy? No comparison to B [in reference to Behati Prinsloo];” “Homewrecking shit bag of a person;” and “Cheap woman from Onlyfans.”

Although Stroh is not innocent, focusing the hatred on her diverts the attention away from Levine – a father of 2 children with a pregnant wife of 8 years who actively pursued sexual and emotional affairs with other women. In fact, barely anyone turned to denounce Levine’s actions because they were more focused on the fact that the person he cheated on was so beautiful.

Critics of Stroh say, “She knew he was married, she knew he had children, so why would she do that?”. This is true, but in that case, why don’t we also ask, “He knew he was married. He knew he had children. Why would he betray his family?”. These sexist double standards reinforce the idea that the woman is constantly to blame and traces back to the reductive phrase, “boys will just be boys.” By normalizing the idea that any mistake made by a man is just ‘in his nature’ and ‘he just can’t help it!’, we implicitly take away the need to hold men accountable, even when we need it most.

And unfortunately, this situation isn’t isolated — men in established positions of authority often wield their power to take advantage of women. And they almost always get away with it scot-free. The widespread vitriol toward Stroh was reminiscent of the collective cultural and social disdain toward Monica Lewinsky following the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal. In both situations, the “other woman” was in a relationship with an older man, which immediately introduces skewed power dynamics and the opportunity for impropriety & humiliation. And though Stroh and Lewinsky share a part of the blame in the infidelity, media reports about the respective scandals did not evenly distribute this blame to the male counterpart of the affairs. Throughout Clinton’s impeachment trial from 1998-99, the public still actively chose to support Clinton and his political abilities in spite of their moral inclination to denounce his behavior; in fact, it may have been this unexpected popular support that kept a cheater in office as President of the United States for two more years. Meanwhile Lewinsky was receiving endless hate, both online and in person, and could barely go out in public without facing ridicule. In her 2015 Ted Talk entitled “The Price of Shame,” Lewinsky discloses how her life was derailed by the scandal, whereas Clinton’s political career continued relatively smoothly.

Stroh’s Instagram comment section reflects the same relentless harassment that Lewinsky illustrated in her Ted Talk. The pattern of demonizing the “other woman” in the media places disproportionate amounts of blame on women in heterosexual relationships, imposing an unspoken decree that women should be responsible for men’s behavior. In fact, in general, the derogatory hostility toward women involved in scandals never extends to the male perpetrator in heterosexual relationships, the one who ruined his own relationship. Think of numerous terms that we have constructed to describe women like Stroh and Lewinsky: “homewrecker” and “mistress.” None of these terms exist for men; rather they are simply regarded as a “ladies’ man” or a “playboy” — phrases that implicitly glorify unfaithful behavior. In fact, Adam Levine cheating on his wife became a meme, downplaying the seriousness of the situation and (undeservedly) removing the blame from him by infusing humor into the situation.

On a broader scale, the sheer existence and popularization of the term “the other woman” is an outlet for general society to fixate anger on women to cope. It’s much easier to blame and disparage a third party stranger instead of acknowledge that someone you loved betrayed and hurt you. In fact, the vilification of the “other woman” further contributes to the misogynistic “Boys will be boys” mindset — women are often shamed for their sexuality whereas men are celebrated for it and even profit from it.

Take The Weeknd’s hit single “Save Your Tears” for example: he sings about ex-girlfriend Bella Hadid crying after seeing him with another woman in a club. By painting himself as an incorrigible person who is bound to ruin every relationship, the Weeknd victimizes himself in a situation where he is really the perpetrator, and then makes money off of this twisted narrative. According to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, “Save Your Tears” was deemed the best-performing global single of 2021, with 2.15 billion streams and making nearly $2 million in profit.

And let’s not forget the trainwreck that is Ned Fulmer. With his net worth of $10 million and fame from being a part of Buzzfeed’s Try Guys, Fulmer made headlines in late September of 2022 when he was exposed for cheating on his wife of 10 years, Ariel. Before his infidelity was divulged, Fulmer had a podcast with Ariel named “BabySteps” in which they shared their experiences in raising their sons. The two also ironically co-wrote a Date Night Cookbook that was sold in Target and shared a series on the Buzzfeed channel entitled “Try DIY” that Try Guys fans regularly tuned in to witness the cute couple together. In fact, many fans regarded Fulmer as a big family guy who seemed, at least on the surface, extremely loyal to his wife and family. But as his cheating scandal was made public, it became clear that Fulmer’s devotion was a facade – rather, he was profiting off of Ariel by appealing to viewers who enjoyed watching marriage content. Fulmer was furthermore revealed to be cheating with an employee, Alex Herring. Herring was an associate producer for Try Guys and was engaged to her long-term boyfriend of 11 years when the affair occurred.

Interestingly, unlike most celebrity cheaters, Fulmer was actually held accountable and faced a flurry of consequences. His role in Try Guys was stripped from him despite his status as a company founder, and went from 1.2 million Instagram followers to 1.1 overnight. A majority of the comments under his Instagram posts question his character and express disappointment in Fulmer’s infidelity: “You definitely caused pain and irreparable damage to the people in this world who love you most;” “You’re not sorry, you’re just sorry you got caught;” “Ariel and those babies [his wife and children] deserve so much better. I am so disappointed in you;” “My heart breaks for Ariel and your children. Men need to start taking accountability for ruining children’s and women’s lives .. shame on you.” So sometimes, cheating men aren’t just let off the hook — cases like Fulmer’s remind us of how men can still be held accountable and receive the backlash they deserve.

Backlash toward Lewinsky, Stroh, and Herring is indicative of the sexist stereotypes we possess toward “the other woman.” Trolls and haters don’t take into consideration that women can be manipulated and coerced into illicit relationships — the “other woman” isn’t always as ill-intentioned, sexually deviant, and conniving as traditional archetypes paint them out to be. Power dynamics in infidelities are more complex and multifaceted, and there exists no such black-and-white, blanket description of cheaters and who they cheat with.

Celebrity infidelity has uncovered the nuance that lies within heterosexual romantic relationships as well as broader patterns of societal thought. Infidelity is about so much more than having a perfectly toned body, symmetrical face, or shiny hair, and there’s no predictor that determines whether or not you will be cheated on. Furthermore, the publicization – and nearly normalization – of infidelity in modern media has brought out ugly parts of society that mercilessly bash women yet place men on a pedestal. For Levine and Stroh, or Clinton and Lewinsky, or Fulmer and Herring, both parties are in the wrong; but it’s important not to hyper-fixate on the other woman. We have to be accountable for both individuals in the relationship and be conscious where we direct our blame and negativity. So the next time you feel like attacking the “homewrecker” or the “mistress,” take a breather and listen to Lana Del Rey’s song, “The Other Woman” instead.