The Paradox of Escapism

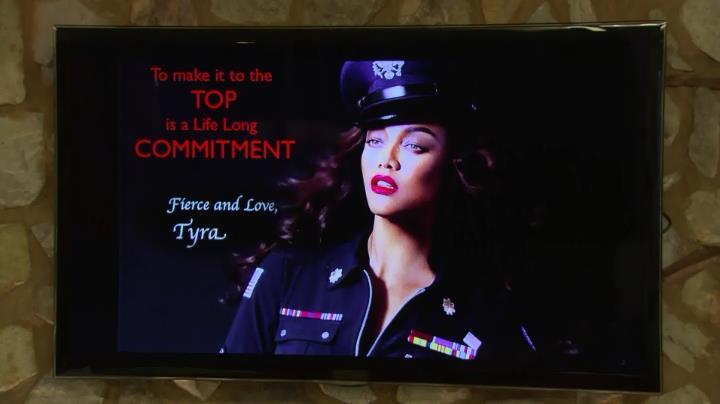

Image Description: An image of a “Tyra Mail” delivery in “America’s Next Top Model” S20xEP3.

Image Credits: Screenshot taken from “America’s Next Top Model” on Hulu

A consequence that has discreetly sprouted from our obsession with the Age of Information — the Age of anything and everything that is gossip, media, and entertainment — has been an individual’s tendency to turn towards “infotainment,” information with the intent to entertain, to escape the hardships of their own life. This process has been described as “escapism” by academics and social media users alike. Overall, escapism refers to an individual’s attempt to avoid the awareness of unpleasant realities in their daily life.

Escapist viewership, for instance, can be watching people being toxic. It gives us the ability to make a social pariah out of anyone we deem “bad,” and simultaneously assume a moral high ground. If you’ve ever watched reality TV, then you know exactly how this feels. Whether it be notable reality TV series like “Tiger King,” “Keeping up with the Kardashians,” “Love Island,” “Selling Sunset,” etc., reality TV commonly depicts extravagant, outlandish, and vain lifestyles in a somewhat factual manner. In recent years, people have been able to watch how the Kardashian family lives, make fun of Kendall Jenner’s failure to cut a cucumber; uncover the inner-workings of big cat breeders in America, and explore the often childish drama of Los Angeles real estate; overall, denying viewers an opportunity to reflect on their own lives all the while judging the behaviors of real people.

To speak from experience, escapism in the form of enjoying entertainment media has resulted in a bit of a paradox. The constant thrum of capitalism, the incessant expectations of productivity and our labor, has left me reaching for anything to forget the invisible hand that tends to weigh me down–even if it’s just for a moment. Recently, I’ve joined my roommate in watching various reality TV shows, including Tyra Banks’ magnum opus: America’s Next Top Model (ANTM).

I reveled in watching problematic people do problematic things because it alleviated the stress I’d put upon myself to be consistently perfect — to smile and nod when I just want to scream. I’ve done problematic things, often spitting out my repressed anger onto those who dared to tread rough waters on a wrong day, so I rejoice that I’ll never be as wildly problematic as the participants of ANTM

ANTM was a reality TV show that ran from 2003 to 2018, purportedly created to introduce diversity and inclusion into an exclusive industry: modeling. Tyra Banks, the famous fashion model and entrepreneur, hosted the show alongside judges like Miss J. Alexander and Kelly Cutrone. The seasons begin with roughly 20 contestants who are picked from hundreds of amateur models who had come to the show’s open auditions. The competitors are then dwindled down to one, who receives the “top model” title, a modeling contract, a fashion spread in a magazine, and various other prizes. As I watch Tyra Banks and her production entourage put their contestants through ridiculous feats in order to unearth the next top model, like walking a runway while scaling the side of a tall building or jumping out of a helicopter for a shoot, I can only sit in awe of it. As the contestants are consistently exploited – modeling and acting unpaid for various brand deals including Tyra’s make-up line just for the 1 in 20 chance of being an arbitrary “top model” – I point and laugh at the vainness and drama of 20-something year-olds under strenuous circumstances, living with people they’ve only know for a few days, grateful to be a part of the audience, to be on the good side of things.

While I consider ANTM —in all its “fierce & love” glory— to be the holy grail of television because of its unabashed portrayal of human greed, vanity, and tenacity, it’s also a prime example of the intersection between capitalism and entertainment media. As media companies have been undertaken by various conglomerates, roughly 6 major corporations now control the media we consume: AT&T, CBS, Comcast, Disney, News Corp, and Viacom. Since mergers are unnecessarily complicated and obscured, it is likely that even fewer corporations create over 90% of what we read, watch, and listen to. With larger corporations managing media, the quality of content has been exponentially diminishing. There is pressure to make more money, more quickly, thus many companies have turned towards the low production value and popularity of reality TV. It allows them to avoid the cost of hiring professional actors, and like in ANTM, can even exploit the average contestant for free labor. There is no need for a script, and the entertainment value comes from the gritty portrayal of humanity to the audience’s pleasure—reinforcing social norms and expectations, and punishing anyone who seems to stand outside of that.

Reality TV satiates the awfully American desire to maintain the rigid norms that guide much of what we deem acceptable and unacceptable. If someone does something we think is bad, we want them to be punished. We hand out tickets, citations, and prison sentences — financial debts that disproportionately fall on marginalized individuals. We shame, we cancel, deny any sort of proximity to mistakes, and withhold any ounce of redemption — social executions that only people from places of privilege can avoid. When I see people being mean to J.K. Rowling on the Twitter timeline, I am pleased, knowing full well that it was only a few years ago I stopped following traditional, conservative beliefs. I point and laugh smugly, even though I’m still poor and J.K. Rowling’s net worth is almost a billion U.S. dollars.

A capitalistic society values “perfection.” The kind of perfection that is presumably the result of productivity and the accumulation of wealth. Reality TV, like social media, is a carrier of infotainment that wrongly assures us of our moral superiority, giving us the content to ignore our own downfalls by showing us, and amplifying, someone else’s. Yet, if you were paid to look pretty and create dramatic entertainment, who’s to say you would act any differently, especially as many of us are individuals who are merely one paycheck away from homelessness?

It is when we come to this mesh of capitalism and infotainment that an unsettling paradox appears within our love for, and even need of, escapism. ANTM might make me momentarily forget about my misfortunes, my poverty, but it is simultaneously the poster child of entertainment under capitalism. It is cheap, it is exploitation, and it is the dumpster fire that makes me forget about my own dumpster fire. Unfortunately, this temporary relief maintains a cycle where I am perpetually upsetting myself. I sit down on my couch after a long day of work, anti-capitalistic study, take my antidepressants, then turn on a TV show that is made possible by capitalism and becomes subject to similar moral hierarchies. Models must smile at the right times, cry at the right times, become a sellable brand, and exert their mind, body, and soul for the win: the top model title.

Most sociology theorists, such as Marx and Weber, argue that capitalist expectations and demands concerning labor and labor value run contrary to human nature. We were meant to create, but modern life exploits our value for the sake of more profit, ultimately alienating us from our creativity and community. As much as I don’t know who made my iPhone, I don’t know who takes my trash to the landfill, who keeps my water running, and who brings my favorite oranges to my hometown grocery store, I’m not expected to care. So I don’t.

I post on Instagram, peel my oranges, and take out my piles of trash, without knowing the exact line of exploitation that has given me the opportunity to do so. I write articles about the absurdity of capitalism, not knowing whether or not this labor has afforded nameless workers any sort of opportunity or value. And I’m not really sure if this distressing reality is one I actually want to know when I’m also just trying to survive.

I turn towards these reality TV shows for a sense of relief, only to be met with a mirror. I laugh, shake my head, and Tweet my opinions to create a permanent history of reality TV stars’ mistakes and behaviors. I ignore my own remarks, behaviors, and perceptions that I would never want to be publicly accused of. While I still assure myself I occasionally look away at reality TV because of its overwhelming glamor and vanity, I may just be trying to ignore how vividly the problematic behaviors of those struggling under the weight of corporate and societal expectations reflect my own survival in a society ruled by profit and greed.