The Revolution Won’t Liberate You, but a Nose Job Will

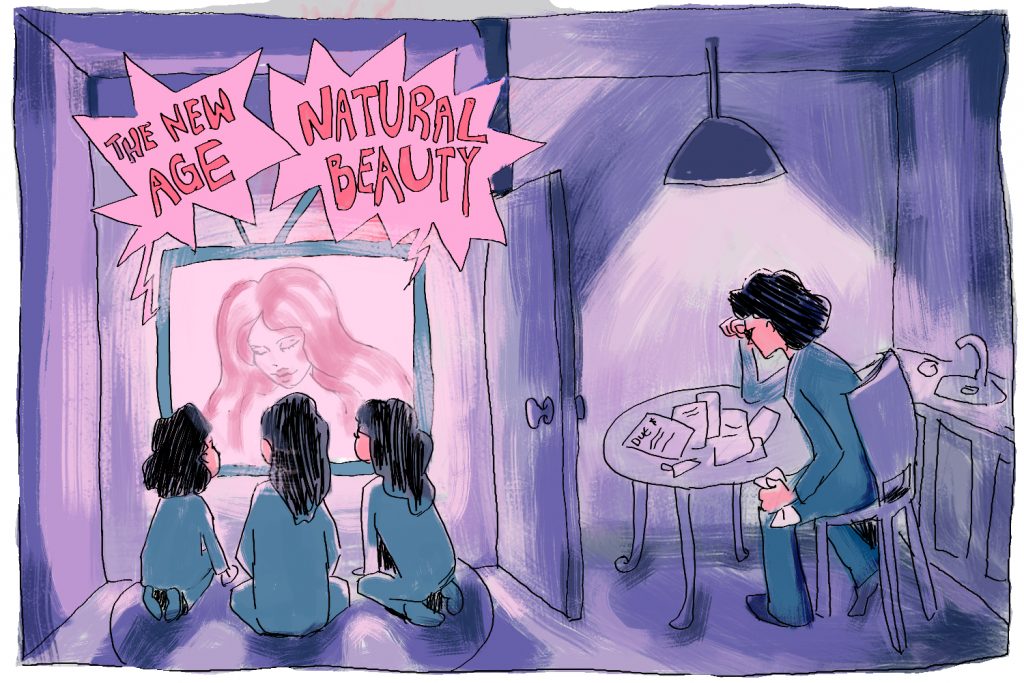

Image Description: On the left side are three kids sitting on the floor in front of the TV watching a beauty commercial. On the right side is a parent sitting down at the table looking down at bills.

“It’s a metamorphosis that occurs with courage, resilience and the pursuit of self-actualization.”

As Steven Williams, the president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, chillingly demonstrated with his statement above, cosmetic plastic surgery has gained an odd reputation as a form of empowerment and self-expression — as if it holds some liberatory power that grants those born without “god given beauty” a chance at the privilege and perceived confidence granted to those just “naturally” and “unquestionably” beautiful.

This framing of plastic surgery is a ploy to make these cosmetic alterations increasingly marketable and acceptable — even encouraged — in a space where cultural notions of beauty are driven by profitability and defined by performative forms of activism that give lip service to revolutionary feminist values of empowerment, creativity, self-expression, and self-love. The rhetoric produced by medical professionals, beauty corporations, influencers, and so-called feminists uses choice feminism — the concept that being able to choose is the be-all and end-all of feminist empowerment — to normalize cosmetic plastic surgery and reframe the conversations we have surrounding it. Accessibility, resolving insecurity, and the value of honesty are central to these conversations.

In this framing, we fail to emphasize the ethnic erasure inherent in many procedures and how American cosmetic procedures — both minimally-invasive and surgical — are deeply entrenched in manufactured beauty standards. These standards are complicated and contradictory: driven by white supremacy, a disdain for ethnic features, yet a fetishization of people of color, and a well-fortified commitment to fatphobic ideals under the guise of “health.” This lack of social reflection has distorted cultural understandings of plastic surgery, shifting focus away from the harm caused by such procedures.

Plastic surgery is not a new concept, nor one restricted to just America or the Western sphere. However, cosmetic procedures within a Euro-American context have grown increasingly popular since World War II, with their popularity and cultural relevance escalating in recent decades. Technological advances have gone hand in hand with the expansion of the cosmetic procedures industry, and the increased accessibility and normalization of procedures have caused the total number of procedures per year in America to nearly triple over the past two decades. These procedures can be divided into two categories: minimally-invasive and surgical. Minimally-invasive procedures refer to injections like Botox, other fillers, skin treatments such as laser hair removal, and non-invasive skin tightening, among others. Cosmetic surgery procedures include but are not limited to breast augmentations (boob jobs), liposuctions, abdominoplasties (tummy tucks), eyelid surgery, facelifts, breast lifts, and rhinoplasties (nose jobs). Since 2005, the expansion of cosmetic procedures has remained largely within the realm of minimally-invasive procedures: in 2005, 8.4 million minimally-invasive procedures were performed, while this number grew to 25.4 million in 2023. Comparatively, around 1.8 million surgical cosmetic procedures were performed in 2005 whereas 1.6 million were performed in 2023. This decrease is largely due to a drastic drop in the amount of nose reshaping surgeries performed (298,000 in 2005 compared to 47,000 in 2023), which initially plummeted after the Covid-19 pandemic. This trend may be accounted for by the expansion of minimally-invasive procedures available for nose reshaping or due to increasing financial difficulties, though the drop off remains a somewhat strange phenomenon. Regardless, the number of cosmetic alterations continues to grow and shows no signs of dropping off in popularity.

Before I investigate the merits of my arguments, all plastic surgery and cosmetic procedures are not the same. There is a clear distinction between procedures done for health-related reasons (such as nose reconstruction for improved breathing, breast reduction to alleviate back pain, or gender-affirming surgery) and procedures done entirely for cosmetic reasons. Gender-affirming surgery is particularly nuanced: for people experiencing gender dysphoria, medical transition is a way to align their body with their gender identity. The way in which this is done may be influenced by the beauty standard, but the act of affirming gender through surgery is not inherently playing into harmful systems of oppression, like fatphobia and racism. Though gender-affirming surgery is related to mental health, as cosmetic surgery can be, the origins of desire for these surgeries are importantly distinct. Gender dysphoria can often be entirely solved through surgical means, and gender-affirming surgery is not harmful to others, while the same can not be said for cosmetically motivated surgery.

For the purpose of my argument and simplicity, I will be using the language of “plastic surgery” or “cosmetic procedures” to refer to the subset of non-health-related surgeries; I am not referring to the more complicated cases. I am referring to the majority of rhinoplasties, Botox and other fillers, liposuctions, and breast augmentations, which are performed on completely healthy bodies to change people’s features. These cosmetic surgeries, compared to health-related procedures, are a direct result of insecurity caused by systems of oppression — fatphobia, white supremacy, fetishization, and ageism, to name a few. We could easily further complicate this argument. What about facial reconstruction for people involved in severe accidents — how might it be tied to ableism? What about surgery to remove loose skin after significant weight loss? What about how unrealistic standards may influence what kind of boob job a trans woman gets, or how facial feminization surgery often seeks to eradicate the facial features of people of color? These questions carry more theoretical weight than the majority of cosmetic procedures, but the point remains: cosmetic procedures are individualized within a broader social context. Plastic surgery gets incredibly complicated, with endless combinations of “what-ifs.” Still, it is worth making generalized arguments about plastic surgery while understanding these arguments have subtleties.

Regardless of nuances, any framing of cosmetic procedures as liberatory, empowering, or “feminist” is dangerous and unsound. The normalization and expansion of plastic surgery come at the expense of oppressed communities, as American beauty standards are manufactured through the marginalization of these groups. There are ways our beauty standard is classist, racist, ageist, and fatphobic. I don’t like throwing around a bunch of “-isms” because of how it assumes personal accountability in broader structures: how can a supposedly individually motivated act be so interconnected with social systems? When we feel intrinsically motivated, we do not like to be told that these motivations are bigger than ourselves. But what about straight and white teeth is so appealing? It has evolved to be a symbol of wealth. And what makes a slim body inherently attractive? Not only is being a particular weight not even close to a direct indication of health, it is largely achievable by the wealthy who have resources and time to diet, exercise, and afford surgeries or weight loss drugs. What about a button nose is better than a ridged or flat nose? One is a symbol of whiteness and the others are common among many non-white ethnicities. Why do we yearn to be wrinkle-free? There is nothing wrong with forehead wrinkles, and there is nothing wrong with aging. Why are plump lips better than thin lips? They seem to be an acceptable ethnic feature, but only on a white body. These desires are all things we would not feel in a vacuum and are also heavily tied to ways we are socialized to see certain bodies — those that are skinny in the right places, white with the right amount of “ethnic” features, and youthful — as entirely superior to those who don’t fit these standards. When we decide to change the way we look, that decision is not an empowering decision to “self-actualization” but instead a result of how we are socialized to have disdain for certain bodies and faces — disabled, “fat” or just not “skinny,” Black and Brown bodies, Jewish noses, etc — and how we privilege and worship an unrealistic, white yet fetishized, youthful body.

Choice feminism is used to ideologically permit and even celebrate such choices. It posits that the ability for women to choose in life — to work or not to work, to wear makeup or not to, what clothing to wear, to get cosmetic procedures — is a fully liberatory ideology. This view of feminism is reductive and frankly regressive to revolutionary attempts to liberate us from the constraints of patriarchy. As such, many feminists recognize the hypocrisy in this ideology and often critique it for its lack of consideration for social realities. Choices are not inherently demonstrations of freedom — they are the results of socialization within a misogynistic society and can be quite predominantly oppressive. Yet, for as much as people critique choice feminism for being an incomplete method for liberation, people walk on eggshells around cosmetic procedures because they fear insulting a woman’s autonomy: a ridiculous and insulting result of the rhetoric that has developed to frame cosmetic procedures as empowering. Bodily autonomy — particularly that of women, people of color, and disabled individuals — has historically been restricted and taken away, so fears regarding insulting autonomy are understandable. Yet, there are nuanced and productive ways to have conversations that reflect how our choices can be harmful or helpful to others, and in this context, plastic surgery is at the expense of others. Invoking introspection for someone who has not reflected on the causes of their desires or the consequences of their actions does not prohibit them from making choices, but instead grants people a better understanding and ability to demonstrate true autonomy. Viewing bodily autonomy — that is, making decisions about our bodies based on what we want and believe — cannot, and should not, be simplified to the ability to make choices regarding our uninvestigated desires. We do not make choices in a vacuum — how we make choices and the consequences of these choices are not constrained to the individual. Though we can never live in a world where the way we think is objective and individual, we can recognize when ways of thinking, and the systems they reproduce, are oppressive.

Plastic surgery is evidently not a tool for liberation. It also is not an approach for combating inequality. Plastic surgery does not give the oppressed — by race or class — a chance at some “equal opportunity” of beauty. Fillers can be almost $1,000 per syringe. Non-surgical skin tightening costs thousands of dollars. Rhinoplasties can cost upwards of $10,000. Liposuctions cost thousands of dollars. For the majority of Americans who are struggling to put food on the table, pay rent, and afford healthcare, the suggestion of cosmetic procedures as an equalizer is laughable. The people we see in media — models, actors, and influencers — are the people who get these procedures done. If others want to do the same, it is a long drawn out process of saving money to be able to afford it, and it is horrifying that people would feel so insecure about their features that they would sacrifice experiences, other forms of consumption, and at times, necessities, for an expensive procedure. The predominant group of people getting plastic surgery in America are, themselves, white, wealthy, and “stereotypically” beautiful. The argument that plastic surgery has different valuation for people subjected to a white supremacist beauty standard who are not themselves white or “the beauty standard” is a scapegoat; it seeks to ignore who can afford these procedures, the harmful standard of beauty they represent, and who is actually getting these procedures done.

The beauty standard is a construct and, as all constructs are, it is up for constant reinterpretation and change. The beauty standard relies on exclusion; hence, as people adapt and change, it must constantly shift to maintain this exclusion, and it does so at a particularly quick rate compared to other constructs. Our bodies are exceptionally “trendy.” Standards shift from the desire to be thin to being toned, to having a fat ass and big boobs, and back to being thin within a few years. Breast augmentations and BBLs are popularized among celebrities, yet we also see a reversal of this as the surgeries become more popular and more people begin to achieve these unreasonable beauty standards. Kim Kardashian, a predominant figure in shaping this beauty standard, has been accused of getting a reduction in her BBL (one she never admitted to in the first place). She can afford to make these decisions about her body without personal consequence. Facial feature standards shift more slowly — button noses, toned jawlines, wide eyes, and plump lips are the current ideal. The American beauty standard shifts seamlessly between the fetishization of so-called exotic features and the idealization of European white standards. Big lips are a predominantly Black and Brown feature, but they have become the beauty standard on white bodies, leading to the popularity of Botox and filler. Plastic surgery has a distinct uncanny uniformity that characterizes its trends. The same flat, button noses are constructed — rhinoplasties do the same thing to each and every nose. Fat is removed from and added to the same places — bigger boobs and butts are desirable, and stomach fat is the original sin. Filler is placed to sharpen jawlines, thicken lips, and prevent forehead and smile wrinkles. These surgeries and non-invasive procedures are not individualized in the way “self-actualization” and “self-care” frame them to be — they are particular to the structures and culture we live in.

The beauty standard is ever-changing, though it is influenced by numerous “-isms,” because it functions on exclusion. The unachievability of the beauty standard is manufactured and replicated by a mega-wealthy few who can afford to surgically adapt themselves to whatever the current trend is, but this is not the case for any other community. It should ignite anger and a sense of disturbance that an ever-changing construct is being enforced in permanent ways, for profit. It is scary that instead of attempting to change a harmful beauty standard — one rooted in white supremacy, fatphobia, and fetishization — we are pushed to adapt our bodies to it, despite the fact that cultural work toward broader acceptance and recognition of beauty would benefit more people. Yet, this is not profitable, and it is not a quick fix. So, instead, beauty standards are seen as inevitable and unchanging, though we see their impermanence in our lifetime. Bodies are seen as malleable and inherently good or bad, despite how our features and appearance are largely outside of our control.

Of those who get work done, the moral valuation of the person and this work is now weighed through their honesty. As a result of celebrities lying about the unrealistic work they got done, movements began calling for transparency in the choices people make regarding their bodies. Honesty is important, but encapsulating an entire movement for accountability around honesty without further investigating the consequences of the wealthy normalizing cosmetic surgery is harmful. Women also often receive misogynistic pushback for plastic surgery, which is not an effective way to critique the consequences of plastic surgery. Through this misguided judgment, embracing plastic surgery through honesty and confidence seems to be the “feminist” response. The reshaping of rhetoric prevents us from understanding plastic surgery in a productive manner. We have shifted to praise and even worship those who are upfront with the work they have gotten done, as if they lack control over some innate insecurity that makes plastic surgery inevitable, or as if plastic surgery is a neutral action with little social harm or impact, and show of a true “girl’s girl” is to be confidently truthful about our choices. This is choice feminist rhetoric, and framing this rhetoric around plastic surgery as dishonest and insecure (immoral) and honest and confident (moral) prevents us from confronting the implications of cosmetic procedures and how we should be dealing with problematic beauty standards.

People speak in disturbingly unbothered ways about plastic surgery, about wanting to get a face lift, a nose job, a boob job, or “preventative Botox.” The choices we make can have harmful consequences. Every time a person with an ethnic nose gets a nose job, they signal to their mom, to their younger siblings, to their friends, and to their community that the nose they were born with, which most people cannot change, is not enough. They send the message that this nose is not only inadequate (something that people learn to understand socially) but that people should destroy their natural features because the way we are born — with the features of our ancestors and of the people we love — is that disgusting. We would never look a child in the eyes, or our friend or mother, and tell them that they are hideous, that a feature of theirs is repulsive. Yet this is exactly what we are saying when we make permanent changes to our body: when we justify this through insecurity, we suggest that a feature is so shameful that we have to eradicate it from who we are. This is what a child understands when they see someone get rid of their ethnic nose or get a tummy tuck. To suggest that plastic surgery is some personal and insignificant choice is to neglect this blatant and alarming reality that happens all around us.

People don’t want to frame plastic surgery this way because it makes them uncomfortable. It is uncomfortable to reflect and recognize that a choice you made to make yourself feel better, one you thought was an act of “self-care,” was done at the expense of others. If that feels dramatic, it at the least made people around you feel even more uncomfortable and insecure with features outside their control. It truly sucks to realize that something you did for your benefit is at the direct expense of others. Yet, these are all emotions and realizations that we can reckon with. What is worse is choosing to ignore these realities and reframe it as a choice for liberation, for autonomy, or in another “empowering” framing. Appearance — distinct from expression — is not a trustworthy venue for empowerment, and pretending as such is dangerous.

American individualism teaches us to resolve personal discomfort at the expense of others through neglect of broader consequences. We are socialized to think of ourselves as atomized from our social conditions, to value, predominantly, ourselves, and to not question why we think or feel certain ways. Capitalistic self-care movements and choice feminism epitomize this. Broader movements that emphasize “mental health” are meant to recognize the stress and pressure manufactured within a productivity-focused society; instead, these movements have inspired people to ignore their obligations to others, to their communities, and refuse cooperation with one another under the guise of often consumption-based “self-care.” Choice feminism encourages women to make choices regarding their bodies, lifestyles, and aspirations without critical reflection on where these desires arise from or the influence of these actions on other women. These are all reflections of how identity and cultural notions of individualism neglect others, as they only focus on how to alleviate individual insecurity and emphasize our “right” to personal freedom and choice, disregarding broader repercussions of our behavior. We have come to weaponize identity and personal feelings, often of discomfort and insecurity, to justify harmful actions because we are so uncomfortable with confronting or questioning why we feel this way.

Individualism neglects the unavoidable reality that everything we do is social. Justifying actions as morally valuable through solely “personal freedom” is a dangerous concept that neglects the impact and restraints of the social systems we live within, including socioeconomic restraints, race and gender ideology, body and beauty standards, etc: all of which restrict the so-called “personal freedom” people claim to enact when they make choices. Every choice we make has social consequences, and to think otherwise is to misunderstand the world we live in. Nothing we do has ever been, nor ever will be, done in a vacuum, and though we may beg, kick, and scream for a moment of exclusion from reality, we can never exempt ourselves from social life and its consequences. Because of our role in social life, we have a responsibility to others, though individualism attempts to posit that we are only accountable to ourselves.

If you take nothing else from this piece, I implore you to take this away: the choice to get plastic surgery is neither an individual choice nor is it a desire that arises through internal means. Plastic surgery is a manufactured social desire, and the beauty standard that influences how we feel about our appearance, how we often change this appearance, wear makeup, and ultimately choose to surgically change, is socially constructed in a way that disadvantages the majority and exploits the insecurities of those — everyone, that is — who do not represent the perfect body. And since the perfect body is contradictory — thin yet curvy, white yet “exotic” and ethnic — the perfect body does not exist. We are all disadvantaged, to different extents, by the severity of the beauty standard, and we are all disadvantaged by the normalization of plastic surgery — the sooner we realize this, the sooner we can alleviate these miseries.

We often make choices and hold desires for changing our bodies that are contradictory to our principle beliefs of beauty being internal or subjective. It is normal to have contradictory feelings and desires, and we do not need to justify each feeling and desire and reframe them as good. We are complicated beings and we can, and do, feel things and want things we are conflicted about or that we wish we did not desire. Weight is a very similar example. It is incredibly normal to wish to change your body: to lose weight in certain places, gain weight in certain places, be toned or more muscular, change our body type, etc. We can understand that a desire to lose weight is a desire that comes from fatphobia, the diet and fitness industry, and the unrealistic idealization of models and influencers. Logically, we know weight is not a direct metric of health. These two desires — to not pander to fatphobia and to lose weight — can coexist, and through introspection we can label these as desires we want to pursue or desires we want to reject. Often, though, we see reframing of the desire to lose weight and have a particular body be shaped by rhetoric regarding health: to be labeled as a demonstration of “taking care of your body” and developing healthier habits, though weight can be completely unrelated to the habits we form regarding eating and exercise. We also can understand that the best way to combat insecurity regarding the desire to lose weight is not to give in to these desires because these insecurities often lie deeper than we posit upfront. This exact framework can and should be applied to cosmetic procedures. You can want to change how you look and still understand that these desires are problematic in our social system. You can desire a different nose, and instead of saving up for a nose job, work towards self-acceptance. And to be quite frank, because plastic surgery is only accessible to the wealthy, most people have no choice but to forever live in insecurity or to work towards this self-acceptance. So if plastic surgery is not accessible for you, I implore you to recognize that idealizing such procedures does not solve the problem of systemic insecurity our society perpetuates. And I implore you, if you are considering plastic surgery, to weigh your contradicting desires and act accordingly, without having to reframe each and every desire as morally pure.

You can want things and be ashamed that you want them. What I am urging you to do is not further shame yourself for this or hold self-disdain, but instead act for a cause bigger than yourself, for the sake of yourself and the sake of others, for the sake of your future children, your family, your friends, and your community. Because your actions are socially consequential, and so your thought process and desires should be considered as such. We are all hypocrites, we are socialized to be. I am urging you to take a stand and do something for the sake of others. Is your choice to not get plastic surgery going to change the world? No. But many people making the choice not to will make a difference. We must remember that nothing we do is in a vacuum, and our choices have consequences. At the least, I want us to stop lying to ourselves and reframing things in ways that make us feel okay, or even good, about harmful social decisions. Humans are infinitely influenced by the systems and institutions around us, but we also shape and manufacture these systems. Change begins with people.

The true revolutionary feminist act that rests beneath the lie of choice feminism is how human experience is defined by growth. The most radical thing you can do in regards to your appearance is accept yourself with a disregard for what you are told to like or not to like. This is not a call for all-encompassing self-love or an over-confident realization of our own attractiveness, but a call to move past appearance as a moral valuation. Being uncomfortable with how we look is a natural human reaction to a world that commodifies appearance and tells us very few bodies are truly beautiful. The experience of learning to love ourselves regardless, to have to look at ourselves, unaltered, in the mirror and confront that we may be uncomfortable with what we see, and accepting this and moving past this is a symbol of growth, an innate part of human experience in the society we live in. And beyond this, our role is to actively work to dismantle the systems of oppression that make us feel insecure and commodify our appearance, to make it easier and easier for each generation that follows us to love themselves, and to reach a point where people no longer have to overcome insecurity motivated by racial, ethnic, body-type, or age differences. This is cultural and this is systemic: as long as we have an economic system that profits off of insecurity, our cultural view of beauty will continue to be exacerbated along class and racial lines. And as long as we believe that wealth can fix insecurity, these oppressive beauty standards will persist. Plastic surgery attempts to cut the corner of true self-acceptance, and it often doesn’t succeed. Insecurity cuts deeper than face-value characteristics — cosmetic procedures attempt to put a bandaid on the gushing wound of superficial self-obsession — and if people get cosmetic surgery despite deep insecurity, then they are taking the easy and consequential path out of the beautiful, diverse reality of humankind.