UCLA: Defend Boyle Heights on Artwashing and Gentrification

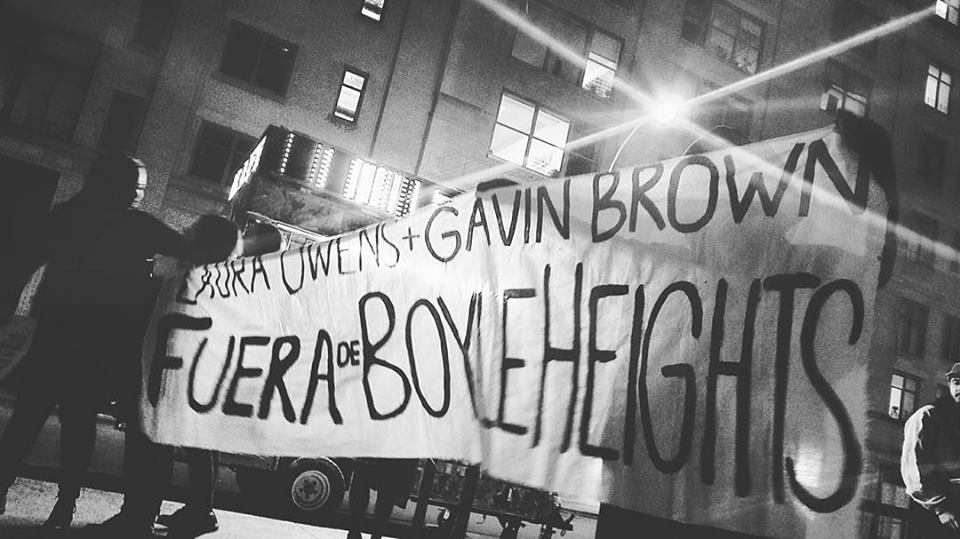

Photo courtesy of Defend Boyle Heights via Facebook.

On Wednesday, Feb. 21, 2018 Fem Newsmagazine co-hosted a teach-in with UCLA feminist collective Voidlab, bringing members of Defend Boyle Heights and Boyle Heights Alliance Against Artwashing and Displacement (BHAAAD) to campus for a discussion on gentrification and artwashing in East Los Angeles. The event was planned in hopes of exposing the complicity of artists and other creatives in the displacement of families in poor, working-class communities.

To cultivate an understanding of the role artists can play in the displacement of marginalized communities many typically claim to support, the presenters spoke on the history and process of gentrification and artwashing within Boyle Heights.

The first displacements in established Boyle Heights occurred in the 1930s, followed by Japanese internment in the 40s, which pushed hundreds from their homes. After the social movements of the 60s and 70s, the federal government began the process of “spacial deconcentration,” attempting to disperse inner city communities concentrated with the power of self-organizing militant people of color (think the Black Panther Party). This process was fueled by over-incarceration resulting from Richard Nixon’s racist “War on Drugs.” The precise targeting of spacial deconcentration is still very much a reality as predatory lending, redlining, and demolition of public housing continues to obliterate low-income communities.

Gentrification is a well-studied, predictable process that takes low-income, working-class communities and turns them into “nice” and “safe” neighborhoods. So “out with the old, in with the new,” right? But these new and improved neighborhoods are formed by renovating or completely destroying low-income housing and small businesses to make room for expensive restaurants, coffee shops, housing, and art galleries.

While young progressives move into the “up and coming” neighborhoods in cities like Detroit, Austin, New Orleans, New York City, and Los Angeles, people who have lived in these areas all of their lives are threatened with eviction notices, rent increases nearly double their rent-controlled payment, and the loss of family-owned small businesses. Gentrification is violence — a death warrant for working-class poor people.

The encroachment of high-end galleries into low-income communities like Boyle Heights is a no-questions-asked necessary step in the gentrification process. Real estate investors are advised to invest where artists are living, with the knowledge that sometime within the next 20 or so years they will turn a profit when gentrification is in full swing. Artwashing is deceitful as it excuses the destruction of low-income communities as “beautification” without acknowledging that long-time residents won’t be able to afford the newly built market-priced apartments. Put simply: artwashing makes violence look pretty.

The usual argument gentrifiers use in defense is along the lines of: “Protesters are trying to get rid of art.” But Boyle Heights already has art — and it has for a long time. In 1987, famous murals were painted in Boyle Heights through the Citywide Mural Project. Images of Brown people and Indigenous symbols tell the stories of the residents of Boyle Heights. The people of Boyle Heights are communicating that white art (or tokenized queer, POC art) in galleries owned by white artists where white people profit is not welcomed in Boyle Heights.

Any left-leaning person will agree that white supremacy is “bad,” but the proclamation that we must make room for marginalized folks to voice their needs must go beyond the internet, representation in the media, and especially representation in museums and art galleries if we are to combat white supremacy. If we want to fight racist police abuse and ICE deportations, we need to stop co-opting the struggle of communities like Boyle Heights and take material action.

An article by BHAAAD calls for artists and creatives to rethink the way their art and politics overlap: “’Progressive’ artists imagine themselves to be separate from this system, and mistake things like ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusion’ for substantive, material concessions, including the forfeiture of accessing certain spaces, as well as opportunities and positions of artistic or intellectual authority. This confusion of ‘progress’ with actual redistribution of wealth and freedom for self-determination is similar to the compromises politicians make in search of liberal solutions that offer no moral or material challenge to the violence, racism, and misogyny of the status quo.”

The process of gentrification is often seen as inevitable, but Boyle Heights proves that militant efforts can change the status quo and support communities in ways liberal legislation has not.

For instance, when the race riots of 1992 took place in Los Angeles, Boyle Heights was already organized. It was one of the first communities to assert that police aren’t essential, as they formed cop-watch programs while simultaneously fighting for community improvements in the face of racist police forces.

In more recent events, the Mariachis and tenants of 1815 E. 2nd Street in Boyle Heights stopped a 60 to 80 percent rent increase demanded by property owner B.J. Turner after a year long struggle. The building, where many mariachis and other tenants have lived for over 20 years, is one block from Mariachi Plaza — a significant cultural gathering place for Mariachis since the 1930s. Through aggressive legal strategy, rent strikes, and unionizing, tenants lowered the rent increase to 14 percent.

By the end of the teach-in, the speakers demonstrated that the movement against gentrification must be explicitly militant and anti-capitalist. Liberal fantasies of peaceful protest and voted reform do nothing as they exist in a ruthless capitalist complex. Furthermore, adhering to the capitalist, individualistic conception of “the artist” separates art from life. We must foster imagination which centers marginalized voices, rebel against the art world elite, and refuse exploitation by institutions.

Artist solidarity is essential to stopping the process of gentrification. Join the boycott: Pull out from the show. Cut ties with galleries like 356 Mission in Boyle Heights. Don’t go to openings. Encourage your friends to do the same.

Defend Boyle Heights, BHAAAD, and their constituents name the boycott an act of refusal: “A refusal to deter to the galleries and their real estate co-conspirators who bathe in the myth of art-as-exceptionalism, refusal to give up spaces to those that have so much already, refusal to assimilate, refusal to participate in systems that oppress and dispose of the marginalize folks in [their] community, refusal to succumb to nihilist chants of ‘inevitability,’ and a basic refusal to be erased.”

—

A full video of the teach in can be found here.