What It’s Like To Watch The Presidential Debates As A Middle-Eastern Woman

Image by Gary Smith via Flickr / Public Domain

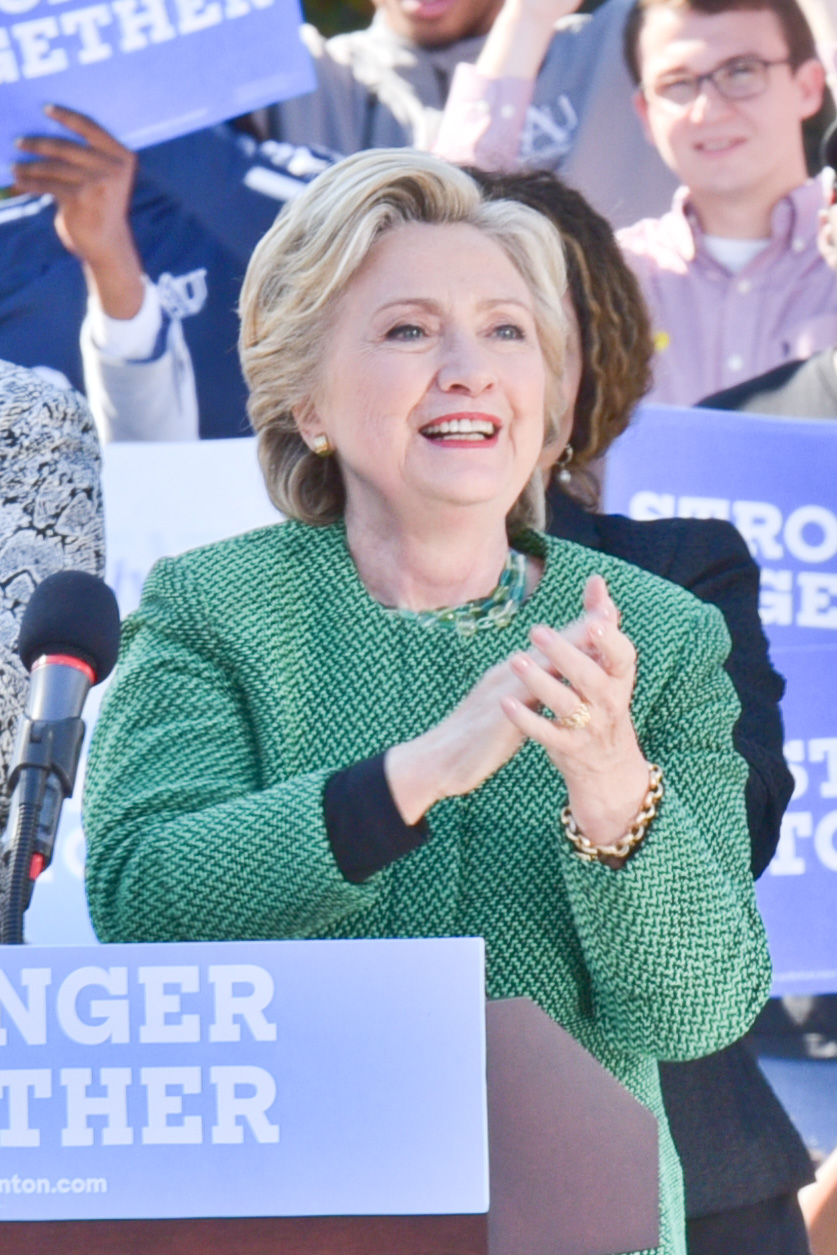

There is little room to debate that this election has been thoroughly soaked in anti-muslim and xenophobic rhetoric regarding West Asia from both sides of the aisle. The first presidential debate between former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Republican nominee Donald Trump on September 26th 2016, was no exception.

Like any politically engaged person, I tuned into the debate hoping to watch two well-informed people discuss their respective detailed proposals of both domestic and foreign policies. Sadly, that’s not what I saw. In fact, accordinging to Vox, only about a half of Clinton’s words were related to the question asked, which seems low, except when compared to Donald, whose words related to the topic only a third of the time. While this should be concerning in regards to all political issues facing the country, it is especially worrisome for those of us with Middle Eastern backgrounds.

Instead of being specific about individual groups, both Clinton and Trump conflate the Middle Eastern, Muslim, and South Asian communities, implying to the many Americans watching that the three groups are synonymous or interchangeable. While this is problematic for many reasons, it has inevitably led to hate-fueled violence toward non-white and/or non-Christian groups in the aftermath of specific terrorist attacks. Being a half-Iranian woman, I found myself in a growing state of distress about how my life will be affected by the comments made during the debate.

As I watched, I saw both candidates speak about the entire region with alarming detachment, as if they were planning to invade and conquer another planet. This is perhaps something I would expect from Donald Trump, but I had hoped that with all of Hillary’s experience, she wouldn’t have engaged in such divisive discourse.

Roughly 20 minutes into the debate, Trump accused Clinton of fighting ISIS for the “entirety of her adult life.” Not only does this indicate his total lack of knowledge about relevant geopolitical issues (and how old Hillary Clinton is), but it creates a dangerous climate of otherism.

Firstly, the use of of the term “ISIS” validates the group’s genocidal warmongering, because it is the title they want to be given. The name elevates them to a legitimate, governing state. If we really want to “defeat ISIS,” we should probably start by referring to them as Daesh to, at the very least, undermine their legitimacy.

Secondly, by deeming them the “Islamic State,” it effectively perpetuates the idea that the 1.6 billion human beings practicing Islam today – including myself – have deep ties to this extremely deadly group. As a result, we become the “other.” We are different from you and are therefore we are the enemy. Hate crimes against Muslims and those who simply appear “Muslim” (read: brown-skinned and/or Arab and/or South Asian) are already on the rise. This kind of thinking only exacerbates the fear I have for my family and myself. The situation is only worsened by the fact that it’s being encouraged by a presidential candidate.

To me, what is by far the most terrifying result of the rhetoric used during these debates is the normalization of xenophobia and the validation of overblown suspicion of Middle Eastern and Muslim people. It is dehumanizing, demonizing, and places responsibility of fixing major international affairs on swaths of individuals rather than on the state actors who caused them.

Take Hillary Clinton’s call to American Muslims “on the frontlines,” for example. She states that every single Muslim in this country has the capacity to “provide information to us that we might not get anywhere else,” essentially making the entire community responsible for the actions of complete strangers committing senseless acts of violence.

So it’s almost humorous that she chastised her opponent’s alienating comments about the Muslim community, whilst making an almost equally reductive remark. The only difference between the two candidates’ stances is that one paints all Muslims as dangerous and the other gives a pass to those that can aid our national security efforts.

Her declaration of support for the infamous “no-fly, no-buy” list only added to the irony of the situation. This proposal has appealed to many as an obvious solution to ubiquitous gun violence even with its glaring problems. The bill uses a watchlist system composed of “known or suspected terrorists” and bars them from purchasing firearms. The vague language used to compile this list has led to a bloated list of suspected “terrorists” determined largely by discriminatory judgements and practices.

In my own experience, the fallout from these statements has augmented how I operate in any given social space. I no longer feel comfortable visiting my hometown after it was named number one “in anti-Muslim hate incidents in the state.” I worry about my family’s safety when they speak Persian loudly in public. I adjust my appearance and clothing to avoid violence from strangers. I constantly find myself explaining that I don’t have to wear a hijab and that I don’t have to get my father’s approval to do things. I am told that I am simultaneously not oppressed as a modern American woman, but I am deeply oppressed as a Middle Eastern one.

Even during the high points of the debate, I could not ignore the harm these declarations cause my family, my peers, and myself. When I hear the potential leader of my country speaking about my community with distrust or disdain, I can’t help but wonder if we as a nation will ever stop this kind of marginalization. Will the political climate settle for us after the election? Or will we simply remain another minority group harmed by the system and people supposedly out to protect us?