White Feminism: An Exploration of Alma Whitaker and the White Settler Movement in Los Angeles

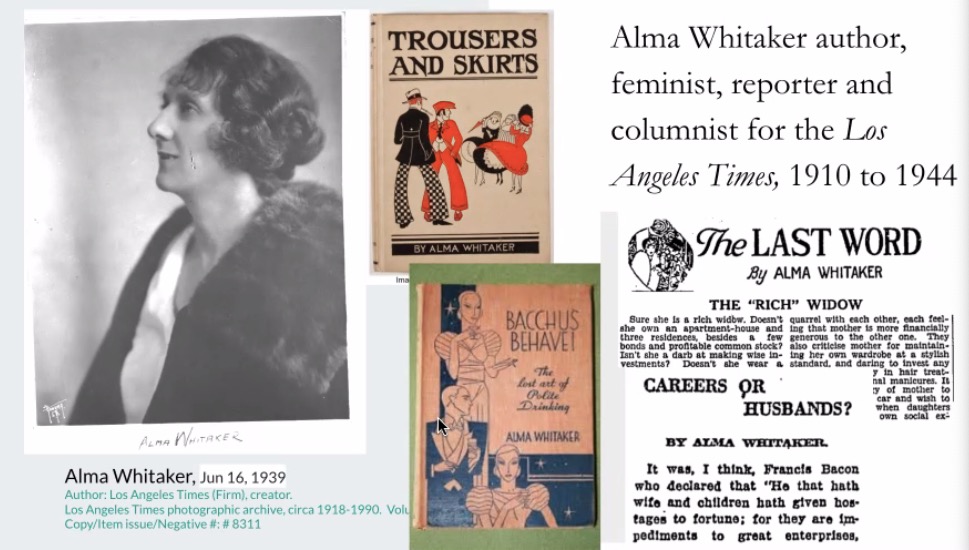

Image Description: A screenshot of a PowerPoint slide featuring a black and white portrait of Alma Whitaker on the left, two of her books in the middle, and a newspaper articles on the right. Text in the upper right-hand corner of the slide reads “Alma Whitaker author, feminist, reporter and columnist for the Los Angeles Times, 1910 to 1944.”

Alma Whitaker was an author, “feminist” reporter, and columnist for The Los Angeles Times from 1910 to 1944. Whitaker was a part of a larger movement of women journalists in the United States in the early 20th century that wrote for and about women. Widely popular at the time, Whitaker’s writings critiqued patriarchal norms and pushed for economic independence for women. Yet, she was a champion only for white women and failed to be inclusive of all women in her message. Instead, she bought into the white settler campaign that was popular in Los Angeles and among journalists at The Los Angeles Times. On Feb. 11, Julie Cohen, a Research Affiliate at the UCLA Center for the Study of Women, hosted a talk entitled “Counternarratives and ‘Copy Cats’: Alma Whitaker, Newspaper Women and Place Making in Early Twentieth-Century Los Angeles” delving into Whitaker’s career and the broader atmosphere among journalism reinforcing and further spreading the white settler campaign that aimed to ultimately make Los Angeles a “white spot.”

At the turn of the 20th century, Los Angeles was in the early stages of its development. At this point, American westward expansion was virtually complete, and settler colonialism was in full swing. The exploitative, racist, and sexist ambitions of the nation were disguised by claims that such expansion was “civilizing” the land and removing anything deemed unfit. With Los Angeles still developing and growing, there was a fantasy among the new settlers to create a whites-only city, despite the Indigenous populations and ethnic diversity that already occupied the land. The more settlers began to enforce their preferred way of life, the more they drew in new settlers with shared cultures, beliefs, and whiteness. This settler fantasy was perpetuated by the actions and efforts of journalists, whose writings reinforced the image of Los Angeles as a white dreamscape.

The Los Angeles Times was deeply rooted in white supremacy and was reinforcing the popular settler fantasy, trying hard to sell Los Angeles as an exclusively white spot. The organization worked to spread racist ideas among their reader base, which directly contributed to social and economic inequity in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles Times either intentionally ignored diverse populations of the city or erased them in one-dimensional, often-racist ways. The guidance of Harrison Gray Otis, the president and general manager of The Los Angeles Times, led to the erasure of ethnic diversity in Los Angeles and after his death, successor Harry Chandler carried on that practice. Otis was known for his conservative political views which were showcased in the paper. The Los Angeles Times under Otis’s lead strongly opposed labor unions. He also became an example of the effect of editorial abuses of power. Under his influence, Otis used the paper to scare citizens by publishing fabricated stories of a false drought to promote the policy for a 1905 bond issue that funded the aqueduct. This aqueduct was planned to be built on land that an investment group that Otis was a member of, the San Fernando Syndicate, had just purchased. Otis cultivated The Los Angeles Times to align with his conservative ideology, and Chandler built on it. Both had ins with the city’s industrialists and rich landowners, and The Los Angeles Times was at their disposal to strategically promote their political and economic agenda.

Whitaker is known for her time working at The Los Angeles Times. After Whitaker and her husband moved to Los Angeles, her husband’s health began to decline. As a result, she had to find a job. She eventually landed a position as a journalist for the Los Angeles Times and started her writing career covering golf events. As a woman early in her career in a male-dominated industry, she had to work to build her standing among her fellow journalists. As she did so, she gained a following and was popular among the working, middle-class white women of Los Angeles. She wrote about the harmful effects of impossible beauty standards and encouraged women to work and be independent. Her pages and others like it that discussed topics related to women were widely popular. Whitaker’s popularity awarded her privileges not afforded to other women in journalism in this era. At the time, it was common to corner the women in the newsroom away from the rest of the staff, but Whitaker pushed against this and had her desk in the center of the newsroom. She was given the freedom to, for the most part, choose her article topics, and she eventually achieved a rather lucrative career in journalism.

Whitaker’s privilege of being white, middle-class and English-speaking gave her the ability to hold the position she did. She constructed a “wholesome white woman persona,” which allowed her to achieve success and popularity among the white women of Los Angeles. Additionally, she had a strong relationship with the editor at the time, Harrison Gray Otis, which awarded her more freedoms. She contributed to TheLos Angeles Times’ overall narrative campaigning for the erasure of ethnic diversity of Los Angeles and feeding into racial stereotypes throughout her writing. She ignored the ethnic diversity of Los Angeles and cultivated a white sisterhood that united her fans. When she wrote about women and the empowerment of women, she wasn’t talking about all women. She was talking to and about white women only.