You Are What You Scroll: From TikTok Brainrot to Digital Realities

We’ve all felt it: the dopamine from each TikTok video hitting us again and again, almost immediately followed by the enthusiasm for the next one. Will it be funnier than what I just saw? Will it perhaps motivate me and give me life-changing advice at 3 a.m.? This digital whirlwind of information rivals nicotine in its addictive pull, and leaves us captives of our phones and what many have come to call brainrot — which, from my understanding, refers to the ways of thinking and talking of a “chronically online” person. The TikTok variant mostly affects Generations Z and Alpha. Granted, finding community, having fun, or simply winding down are some of the reasons people may end up on social media, and its free nature makes it incredibly accessible. But capitalism will always find ways to commodify everyday casual actions to generate profit, often unwillingly making us the product. In the case of social media, it is the perfect low-effort, high-reward market since we produce, consume, and pay for all the content. The attention economy thrives in that environment, where our focus is a currency exchanged for entertainment and corporate profit.

My goal isn’t to be moralizing in this article, as I think I’m truly no better than anyone reading this. My attention span is not what it used to be, and I am always five scrolls and three “I have to lock in” moments away from actually doing my work. But the fact is, the TikTok algorithm is proof of the attention war playing out on our screens that extends beyond our naive understanding. TikTok grabs and drowns us, its algorithm perfectly tailored to have us engage continuously. A video you interacted with suggests you’re a liberal. Here are 10 more exactly like it, to reinforce your views. Did you engage with an “Am I the Asshole” Minecraft parkour Reddit video? You’re cooked, it got you for the next three weeks. Lock in, tech giants such as Meta or X do not entertain us out of the kindness of their hearts: the longer we stay on their platforms, the more advertisements they can display, and the more data they can collect about preferences, behaviors, and desires — all of which can be leveraged for profit. Looking at the term brainrot itself, it might not be fair to categorize it as a unique TikTok phenomenon. Indeed, this seems to be a general issue where all our favorite apps use the same process. Yes, even peaceful Pinterest… This “dopamine rush” can come from anywhere: validation on our new LinkedIn achievement, latest Instagram post, or last TikTok comment, further intensifying the exhilarating experience.

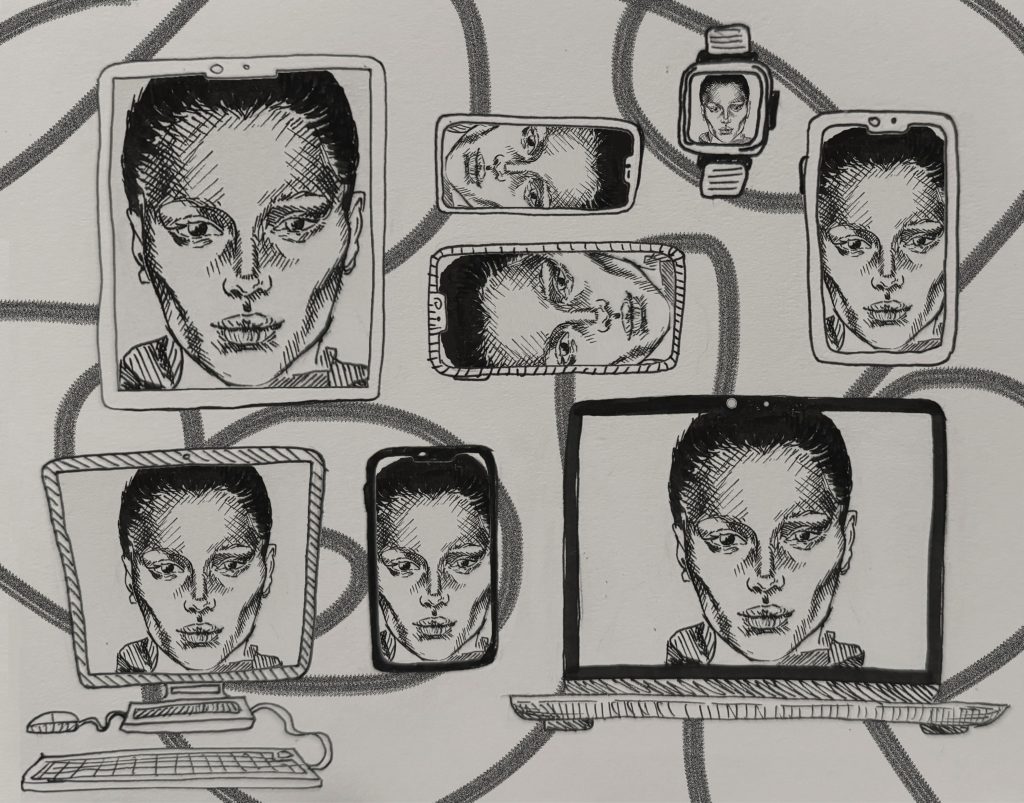

The attention economy is booming precisely because our attention is fraying; it thrives on keeping us endlessly engaged, even as it chips away at our ability to focus and be present. I have to say it, my parents were right: it is that damn phone… We must face the fact that the relentless fight for our attention has affected us all to the point where people have to go on social media detoxes (which hints at the toxic nature of the relationships we hold with our devices), with younger generations affected by the phenomenon tenfold due to growing up alongside these platforms. The capitalist growth model that prioritizes development at the expense of social and environmental health is central in the operation of tech corporations such as Google or Amazon, which tend to value profit and engagement over a user’s well-being. The effects are diverse, from reduced attention spans to mental health issues, and larger societal polarization (not necessarily political, by the way), all driven by platforms that manipulate users for maximum engagement. Social media has transformed from sterile platforms into dynamic spaces that reflect individual personalities and identities through online personas, mood boards, and curated aesthetics. It is not rare to want to give the “vibe” of a soft girl, earthy boy, or cool artistic person through a username, the music on your story, or the picture layout in your latest Instagram dump. Such behavior explains the success of the MySpace era, where users were able to showcase their unique experiences, humor, and style through hours of code. The sheer effort poured into these platforms made them, in a sense, cherished and calculated virtual extensions of the self.

However, this personalization can also foster self-centered engagement. TikTok creator Sarah Lockwood describes this as the “What About Me” effect, also called the Bean Soup theory — an impulse to tailor content to fit personal relevance, and a failure to recognize that the world doesn’t revolve around one’s For You Page. In this one instance, a bean soup recipe was flooded with comments from people asking “What if I don’t like beans?” This type of absurd engagement can be trolling (to a certain extent), but also most definitely showcases some users’ contentment with their hyper-specific digital bubbles built by the algorithm. This pattern demonstrates how digital spaces, driven by algorithms and hyper-personalization, encourage users to filtrate content on the scale of personal relevance, often at the price of broader, shared understanding.

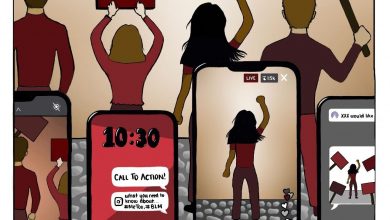

While individual expression and identity development are encouraged (and good, in my humble opinion), hyper-personalization can lead to larger societal problems, such as cultural polarization. For example, despite being described as the “woke” generation that believes in change and acceptance, with increased access to education, cancel culture, and social awareness, conservative beliefs have been thriving among Gen Z. This is particularly true in the case of “Red Pill” content, which is usually conservatives/men’s rights activists discussing the “truth” (read: opinion) about societal bias against men through anti-feminist rhetoric and misogynistic views. Drawing from the film “The Matrix,” the members of that digital community are choosing to see the supposed ‘truth’ about social dynamics by taking the ‘red pill’, as opposed to the ‘blue pill’ which keeps one in blissful ignorance. The way they see it, recognizing the oppression of women as real and the fight to dismantle patriarchy through “woke” conversation (ie. considering centuries of colonialism, and racial and sex-based violence) is blue-pilled and a direct attack on “manhood.” Needless to say, such logic is wrong, but beyond that, also dangerous. Reflecting post-election results, there is a direct link that can be established between Red Pill content/conservative digital realities, and its influence on young people’s opinions. We often talk about opinion being built during primary and secondary socialization, and it is without a doubt that younger voters now also rely on their virtual community to make their choices. As such, the emergence of alt-right/Red Pill creators (think Joe Rogan, Jake Paul, Candace Owens, Ben Shapiro, etc) proudly endorsing Trump is directly correlated to Gen Z’s interest in the figure amidst controversy. These online movements have contributed to Trump’s election in 2016, and also this year, despite the growing influence of the “Gen Z for Change” progressive ballot, – which similarly leverages the power of social media and content creators to drive tangible progressive change on the ground. All in all, these discrepancies highlight how algorithm-driven silos can magnify conflicting beliefs, even among a generation associated with progressive principles. Regardless of political affiliation, it is important to recognize the danger that can come from only ever hearing from one side of the spectrum.

But even beyond politics, tech companies exploit users of marginalized communities through digital individualism, profiting from the commodification of cultural trends and identities and controlling narratives in ways reminiscent of “digital colonialism,” which shapes e-culture while frequently marginalizing and exploiting communities. For instance, TikTok’s viral content often draws on humorous, organic material and African American Vernacular English (AAVE), transforming them into widely used expressions and jokes. This dynamic frequently leads to cultural appropriation, especially when people do not acknowledge its roots. I can recognize that global Black culture is tremendously influential and organically embraced by people from all backgrounds, which is not inherently negative. However, it becomes problematic — and ironic — when people fail to acknowledge its origins, instead separating themselves from the Black community while appropriating its cultural work. A stark example is Saturday Night Live’s “Gen Z Hospital” sketch, where millennial-like characters insult the younger generation by imitating their verbiage through frequent (and erroneous) employment of AAVE: “cuh,” “deadass,” “bruh,” and the iconic sentence “it’s looking like cap” (stellar one, I must say). Despite being written by Michael Che, a millennial Black writer who claimed to be unfamiliar with AAVE — what the hell, sure — the comic embodies how cultural aspects can be diluted and commodified into trends even with the presence of Black writers (which is not too surprising, we don’t all share the same views). This phenomenon reflects a larger systemic problem of cultural exploitation propagated by the entertainment and technology industries, which reduces important cultural identifiers to surface-level gags. This process mirrors that of earlier eras, like Vine (another short-form video-sharing platform), where cultural references and language were trivialized for mass consumption, often at the cost of depth and authenticity. In such environments, cultural elements risk being stripped of their original meaning and diluted into simplified, and sometimes inaccurate, trends. This trend not only erases the rich history of AAVE — whose roots extend far beyond platforms like TikTok — but also marginalizes the diverse communities that have long spoken of it. AAVE is not confined to any one generation but is part of a living, evolving tradition passed down across ages. When reduced to fleeting trends or simplified slang, the people who use it are erased too, their cultural contributions reduced to mere aesthetics, rather than recognized for their depth and significance.

Consider two people you know who are vastly different — for instance, who vary in socioeconomic background, academic interests, or personal hobbies. Despite these differences, they likely share a connection through their phones, scrolling TikTok or Instagram Reels and using phrases like “You’re cooked” or “I gotta lock in” This shared digital language illustrates how social media’s for-profit nature has a nuanced effect on culture; on one hand, it bridges gaps between even the most diverse individuals, but on the other hand, it comes at the expense of reducing complex cultural expressions to viral catchphrases. Everyone brings their unique experiences, culture, and humor to the internet, shaping and sharing trends. If you’ve spent any time in TikTok comments in 2024, you’re familiar with phrases like “My crew, let’s (…),”; “I’m gonna hold your hand when I say this.” or “Just put the fries in the bag.” No one knows exactly who started these “pre-baked” sentences, but the takeaway is clear: internet culture is a culture of its own that shapes self-perception and community. The bivalent nature of this phenomenon is quite fascinating. Being so enthralled in those digital realities does push us to be more self-centered, but there is also some truth in saying that the community aspect is real and — to a certain extent — positive! How does your engagement shape and reflect society’s broader trends? How have your scrolling habits shaped your life and choices? Our interactions online are often dictated by the drive to consume and be consumed, a cycle rooted in capitalist goals of maximizing attention and profit. The personalization of content creates hyper-individualized bubbles that can limit awareness and empathy, keeping us focused inward. At the same time, marginalized communities strive to use digital spaces to amplify their stories, though they frequently face the risk of being commodified or co-opted by powerful corporate interests. This complex situation can blur the lines between a safe space and an echo chamber, highlighting how these structures can simultaneously offer hyper-personalized content that fosters connection and validation but also reinforces insularity and a one-track-minded understanding of the world around us.

If you’ve made it this far without scrolling on Instagram or taking a TikTok break, you’ve already taken a little step toward combating the flow of unending content. Now, while it might be funny to refer to yourself as a chronically online individual (#me #guilty), I hope this article can help you recognize how central our virtual reality can be in shaping our very real world. Reclaiming control of your attention is more than just a personal choice; it’s a significant act of disobedience against institutions that commodify our every move and profit off of far-right radicalization. While actions such as digital detoxes and mindful involvement are effective (and recommended) at the individual scale, meaningful change takes a collaborative effort. To raise awareness, begin by questioning excessive digital consumerism in talks, especially with loved ones. Advocate for systemic policies that keep digital businesses accountable, such as banning addictive designs and improving algorithmic transparency (OpenAI, I’m talking to you), especially when it disproportionately affects young people and marginalized communities. Finally, encourage projects that promote disadvantaged voices and establish equal, authentic digital communities. Resisting oppressive frameworks allows us to regain agency and work toward a more conscious and connected digital future where capitalism doesn’t get to exploit us, or even better, is dismantled completely.