“Cuba Is…” Exhibit Review

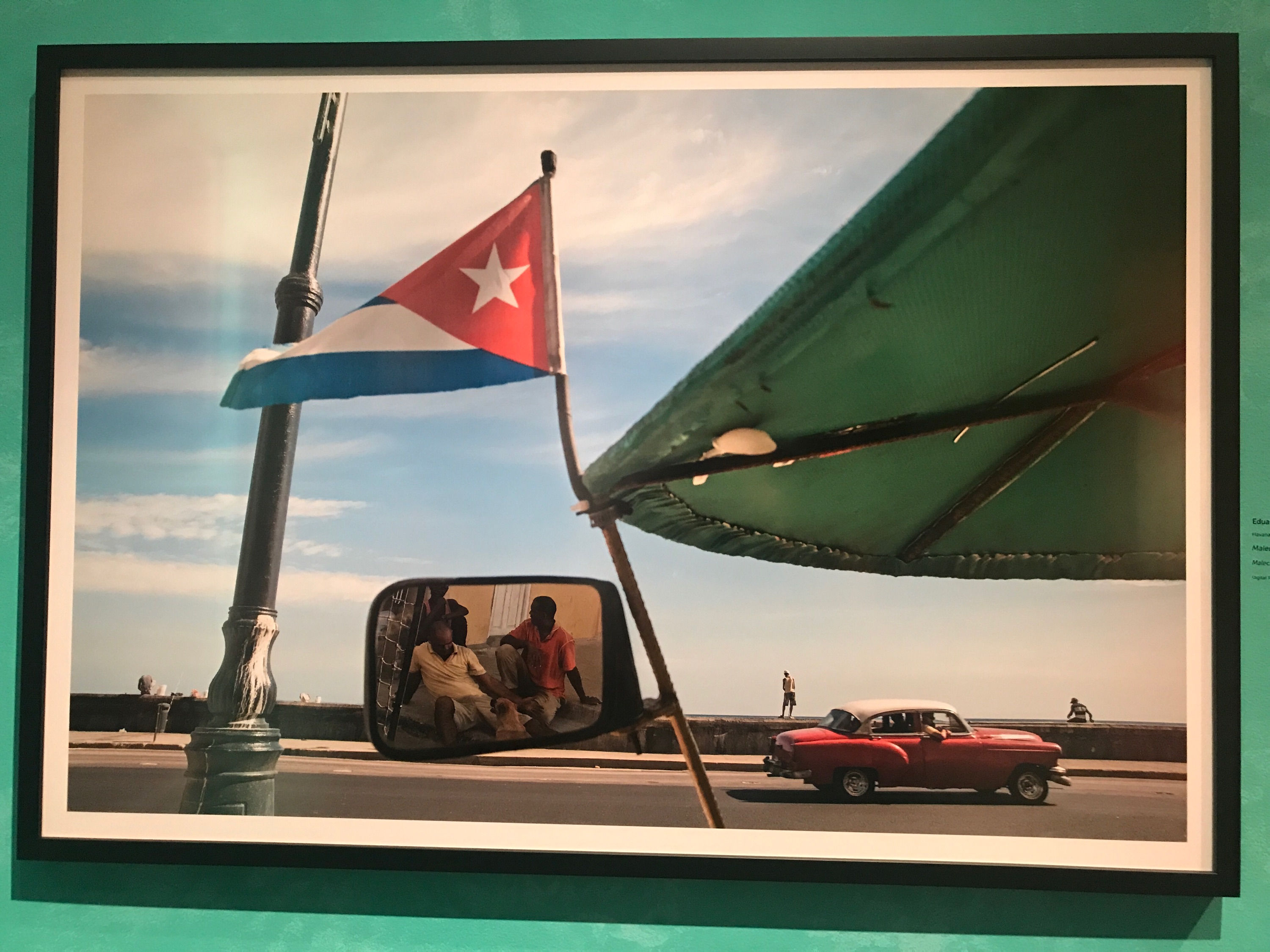

Photo by Quincy Irving

Recently a friend and I visited the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles to see the “Cuba Is…” exhibit. Although I was excited to take in the art, I was skeptical about which narratives would be present in the exhibit. Given my personal experience, this skepticism is not without reason: more often than not, images of Cuba are captured and consumed through a socially, racially, and economically privileged lens.

Admission to the gallery is free, making the art accessible to people across the spectrum of financial privilege. The space features over 120 photographs that are organized according to different themes like artistic subculture, poverty, sexuality, and race in Cuba. A description of the “Cuba Is…” exhibit on the Annenberg website reads as follows:

“Born from indigenous, African and European roots, divergent politics and limitations in communication and commerce, the Cuba seen in this exhibition goes beyond the folklore and offers new insight into its current reality.”

The phrase “new insight” and other patronizing language in the description is telling of who is expected to view and learn from the art. In other words, it implies that the targeted audience is American (specifically people who aren’t of Cuban descent), given that few Americans have directly interacted with Cuban culture.

Annenberg calls the exhibit a “rare, immersive look into Cuban life” – but rare for who? In many of the conversations I’ve had with Americans who haven’t visited the island, I’ve noticed an alarming fetishiziation of Cuba as a “mysterious” and distant place, a reality removed from the eyes of the world. This perspective makes me uncomfortable because it engages in the process of “othering” an entire population based on assumed experiences of access, knowledge and exposure to Cuban culture and politics. Additionally, very seldom is the notion of an American (and inherently capitalist) gaze dealt with in the context of generating, analyzing and discussing images of Cuba.

What exactly makes Cuba so captivating to Americans? Rarely is the complicity of the American government in the oppression and plight of the Cuban people interrogated in these spaces, rather a perplexing curiosity driven by the desire to “discover” an unknown or virginized place. Because tourism is its largest and most successful industry, Cuba is now treated by Americans as a spectacle meant for foreign, capitalist consumption, rather than a real country made up of real people.

Photographers Elliott Erwitt, Leysis Quesada, Raúl Cañibano, Tria Giovan and Michael Dweck are credited with capturing the poignant and striking images of Cuba that decorate the walls of the gallery. Only two (Leysis Quesada and Raúl Cañibano) of the five photographers are Cuban, and the rest are American.

It is true that all creatives bring their personal biases into the process of creating art. My concern, however, is with those who undertake the responsibility of capturing the so-called essence of Cuba and the complexities of its people, without putting an awareness of intersecting privileges and identities in conversation with the art that they produce.

For instance, the photographs taken by Giovan dominated the art space in a manner that felt intrusive and rehearsed to me. Giovan photographed the moments, sites, and people that spoke most powerfully to her, at the risk of sacrificing narratives that do not connect to her personal experience or understanding of the island and its culture. Not once in the gallery did Giovan acknowledge her privileged identity as an outsider looking into a culture she isn’t a part of. That isn’t to say that people who aren’t a part of a particular culture should be banned from exploring, appreciating, or documenting it, rather that they must be conscious of where they do and don’t fit into certain spaces.

As I made my way through the gallery, I became curious as to who profits the most from a project of this magnitude – did any of the subjects of the photographs and videos, most of whom live in poverty and struggle with economic crisis, receive monetary compensation for their time and talent? Who deserves to reap the benefits of presenting this “rare” art to the world, if not Cubans themselves?

The misleading representation of Cuban culture in capitalist spaces is personal to me because of my ethnic background and ties to the island. I am a 19-year-old Afro-Cubana who was raised in a two-parent household in DC by my black Cuban father and my white Spanish mother, both of whom migrated to the United States in search of access to better education, work opportunities, and financial stability. As I walked around the gallery, I saw very few explicit representations of blackness, or at the very least commentary on how it has shaped much of what the world considers to be emblematic about Cuban culture.

The gallery’s section on race was limited to a single photograph, which showed a black man sitting in his underwear with his back to the camera. The absence of images that focus on the nuances of blackness within the socio-political and cultural contexts of Cuban society and government is telling of the limitations of sharing art through an outside lens.

The pride I feel about my connection to Cuba stems from the African roots and legacies of my heritage rather than the nationalistic ideologies that outsiders may associate with the country itself. Despite the project of cubanidad that the Castro regime enforced upon the people of Cuba, anti-black racism pervades social, economic and political relations across the island. The political tactic of cubanidad aimed to erase racial divisions between Cubans while instilling a sense of interracial or interethnic national identity among them.

In hindsight, pushing an agenda of colorblindness and racial unity has done little to correct the socio-economic disparities that Cubans face along racial lines. Given that the politics of race have formed a great part of Cuban history (from colonialism until now), I would’ve liked to see a greater representation of the racially oppressed and marginalized people who make up Cuban society in the art space.