Featured UCLA Feminist: Saloni Kothari

Photo by Madison Thantu

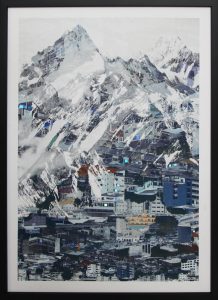

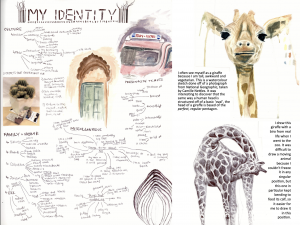

Artwork by Saloni Kothari

It was fourth grade during P.E. class. Saloni watched her friend Ben run from one base to another. “You run like a girl!” yelled one of Ben’s friends. “Well, if you run a little faster you can too!” Ben quipped back. Such a quick witted response was characteristic of the young boy, but this statement in particular had a profound and lasting impact on Saloni. It was among the first of seeds that planted the movement of feminism in her mind.

Second-year UCLA student and artist Saloni Kothari brings an interesting perspective to feminism — one that is rooted in her experiences growing up in Thailand while being raised in an Indian household. This memory of her friend Ben serves as one of many “feminist awakenings” in her life.

To Saloni, feminism is not about empowerment, because women are already powerful. Rather, it is about changing how people perceive that power, including women themselves.

Saloni’s passion for art began at the young age of four, an endeavour that she has continued to pursue throughout her life. As a student artist and tour guide for the Hammer museum, Saloni uses her creative outlet to explore themes of identity, mental health, and self-empowerment. One of her works is a self-portrait featuring her face superimposed with the features of a giraffe. Identifying with this animal — both are vegetarian, “awkward,” tall, and sensitive to sound — this work served as a very candid depiction of who she is, and is a reflection of the “honest art” that she produces.

Growing up in a conservative Indian household in Thailand, Saloni found that many misogynistic ideals were ingrained in her from an early age. When her family hosts guests, it is the norm for her and her sisters to “mom the kitchen,” bringing out the drinks as the men converse. However, Saloni’s education at an international school eventually exposed her to many feminist ideals, leading her to question the social and cultural constructs that she had known since birth.

Upon arriving at UCLA, Saloni found herself faced with the classic dilemma of selecting an education and career path. She came in with the mindset that she “was going to be a STEM major” in order to prove that she was “smart and powerful.” It took time to recognize that she was forcing herself to pursue a path of science for the sole purpose of defying stereotypes, in spite of the fact that she knew it wasn’t her passion. This series of difficult decisions prompted her to examine what empowerment meant on a personal level, and question her tendency to be a people-pleaser.

Having acclimated to the drastically different social norms and gender expectations on UCLA’s campus, Saloni has learned to coexist in the two distinct cultures of American college and life back home. She actively tries to roll with the things that she doesn’t necessarily agree with and recognizes that much of the transgressive behavior is largely a result of the atmosphere in which others grew up in.

With regards to the future of feminism, Saloni believes that we are nearing the point where feminism becomes a universally understood and supported movement “about gender equality, not superiority.” She hopes that men will assume a larger role in this fight to create an atmosphere where both genders are equal.

Saloni has already witnessed men engaging in the fight for gender equality — one pioneering the feminist movement is in fact her own brother. Suyash, an outspoken activist in his community, hosts local workshops related to the harmful effects of enforcing gender norms on children, inside both the classroom and the home. Suyash‘s most recent workshop centered on the fact that gender stereotypes begin in the household, and are, whether intentionally or not, enforced by the way that parents raise their children.

For Saloni, it is young men like Suyash and her childhood friend Ben that are embodying what Saloni hopes is the future of the feminist movement.

Saloni also recognizes the pivotal role that art can and should play in the feminist movement. Seeing that “we live in a visual culture, when you have [a] visual stimulus that’s controversial or shocking it does grab attention. There are a lot of artists, like Adrian Piper in the Hammer museum, who make that [controversy and shock effect] the central theme in their work.”

Saloni believes that more feminist art in the public sphere, such as street art, would help augment the movement, as the placement makes such topics unavoidable. It’s not confined to the insides of a museum’s walls. It’s out there. Even in terms of how certain products are designed, such as toys, or marketing for items like makeup — the colors, choices or body types that are featured are artistic decisions that can help support the fight for gender equality.