How Not to be a Harmful Voluntourist

Illustration by Laura Yau.

As the world becomes a smaller and smaller place and news becomes easier and faster to access, more young people in the supposedly “developed” world are coming to know of the poverty and devastation affecting millions in the so-called “developing” world. Naturally, this information shocks and pains them—they feel compelled to help. As beautiful as that narrative sounds, here’s what that story of “empathy” actually looks like.

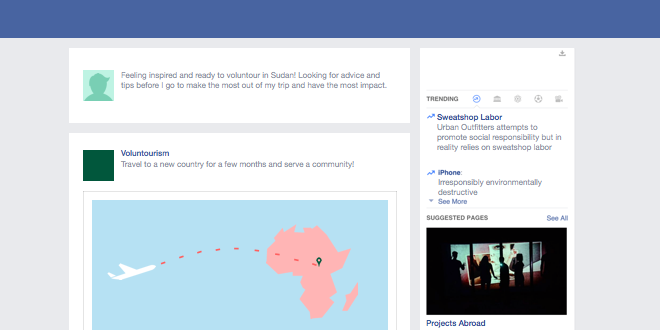

First-World Fred walks out of Urban Outfitters happily clutching in one hand a shopping bag holding their brand new joggers (produced by sweatshop labor) and in the other hand their (environmentally destructive) iPhone. As they head home, they decide to check out what’s happening on their Facebook newsfeed. After a few minutes of scrolling, Fred sees an article like this one about the African orphan crisis that one of their classmates shared with the caption, “Too heartbreaking not to share, show your solidarity everyone!” Shocked and, indeed, heartbroken, Fred wonders desperately how they can contribute. A few links later, Fred finds a program like Projects Abroad, which boasts “hundreds of programs in over 25 developing nations.” Fred muses over how they’ve been wanting to travel and thinks, “This would be a great way to see the world and help the starving orphans!”

So, Fred decides to become a voluntourist and sign up for one of the many programs giving privileged Westerners the rare opportunity to act on their “commitment to helping others and [their] desire to discover a new culture.” Of course, this “commitment” comes in the form of a few weeks or months in a country Fred’s only heard of a handful of times about prior to departure. But they figure that’s not particularly relevant anyway—the point is that they’re spending a lot of money and like, their whole summer, to help these people! Besides, Fred is sure they’ll pick up any absolutely imperative knowledge on the trip itself. Fred doesn’t speak the language of the people they intend to serve and doesn’t intend to learn. Fred doesn’t worry about this either, because the program provides them with translators and other types of coordinators to properly organize the “activities” during the trip.

First-World Fred’s story is not uncommon; in fact, many Westerners planning to serve abroad share the same mentality and rely on the presence of “voluntourism” agencies and the programs they provide. Voluntourism at first glance appears like a good way to integrate a desire for travel with a desire for service. Unfortunately, the reality of voluntourism is that it is likely to harm the communities it intends to serve.

Voluntourism is a new manifestation of colonialism, and thus a dangerous phenomenon. Untrained volunteers who don’t intend to stay more than a few months at most threaten the long-term stability and sustainability of a community that they visit. By painting houses and erecting schools that could have been built by locals, voluntourists threaten the earning potential of the very natives they’re trying to help. In addition, their travel by planes, trains, or automobiles contributes to environmental destruction. Perhaps most onerously, voluntourists play into the “white savior narrative” and perpetuate such oppressive ideologies as Eurocentrism, colorism, and linguistic imperialism (in the case of programs intending to teach English abroad).

Now, this might all sound very intimidating, but fear not, tentative voluntourist! There is a way to be a voluntourist without being First-World Fred, and it comes down to this: you need to want to serve the communities, and not your ego or your resume. If you’re really interested in putting your efforts and talents towards serving underprivileged communities abroad, keep the following points in mind:

1. Do your research.

If you sincerely intend to make a difference in a community, you’re going to have to concentrate your efforts on recognizing, and then relinquishing, your privilege. Know where you’re going and who you’re serving. Research the geography of the area—contrary to popular belief, there are parts of India that experience snow, and there’s more to Africa than the Sahara and the rainforest. Read up on the history of the region and the cultural traditions, and understand that there will always be things you don’t know. The key to being an effective volunteer is humility.

2. Locals come first, always.

Let me say it again, for the people in the back: voluntourism is not about you. When looking for an organization to work with, make sure that local communities are the priority. Which is to say that locals are doing as much of the work as they can, earning as much of the money as there is to be earned, and approaching individual empowerment. A company that adheres closely to this philosophy is the social enterprise Aspire Food Group, which is “developing insect rearing technologies to empower small hold farmers to breed their own insects,” contributing to both economic independence and food security.

3. You might not actually be needed.

Everyone wants to make a difference, to be special and groundbreaking, but in the case of volunteering abroad, you just might not be. If you can’t stay for longer than six months or if you have no real quantifiable skills to contribute (no one in Africa needs you to paint a house or teach their children English), consider traveling for cheap without volunteering. First-World Fred is wrong; sometimes, any help isn’t better than no help.

Truth be told, First-World Fred doesn’t have bad intentions. People like them want to see the world and help people who are struggling. Regrettably, it’s very easy to be a voluntourist who leaves their trip having helped very little beyond their self-esteem. If you’re a traveling and volunteering enthusiast, remember to stay suspicious, stay educated, and stay humble before going on any kind of volunteering excursion.