March for Science – and Immigration?

Image by Janaki Sheth

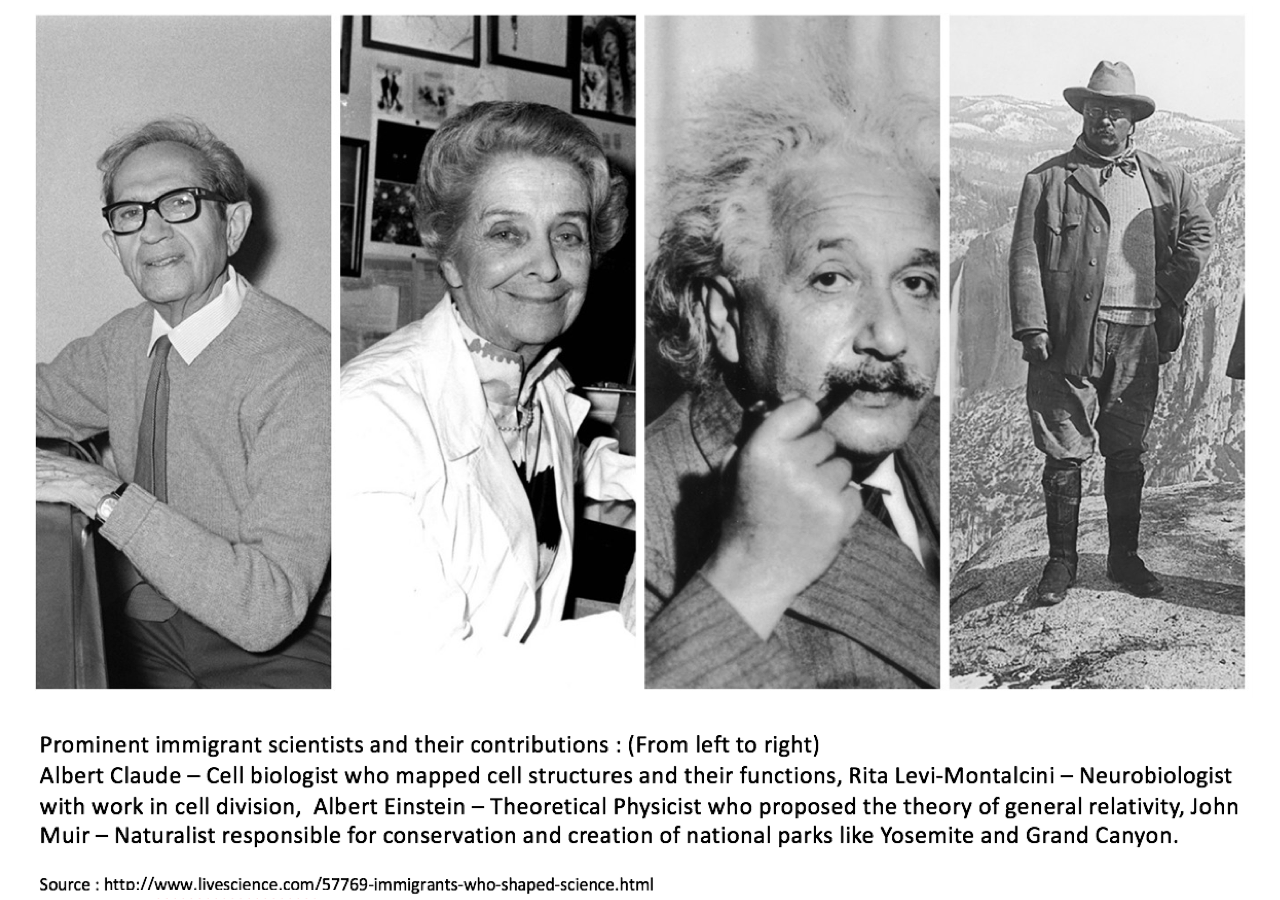

On April 22, citizens of six continents marched to defend the scientific method. However, unbeknownst to many is the history of contributions of immigrants to scientific and economic progress in the United States. Foreign-born naturalized citizens have been etching a mark across several arenas — medicine, military technology, and entrepreneurship, to name a few — and have even upped the numbers of Nobel prizes awarded for work accomplished in the country. Thus, the study of science is affected not merely by the policies for defunding it, but also by the government’s laws on immigration.

Important immigration laws were passed in the last 50 years easing the entry of foreigners for work. These acts have consistently been scrutinized by the debate on job security and cultural homogeneity. Non-Americans face several checks and barriers to enter the States, with a visa for a student or a professional scientist taking three to eight months to process. While American citizens defend science, they should be mindful of the potential effect that stringent and unwelcoming immigration policies could have on scientific research and medical progress.

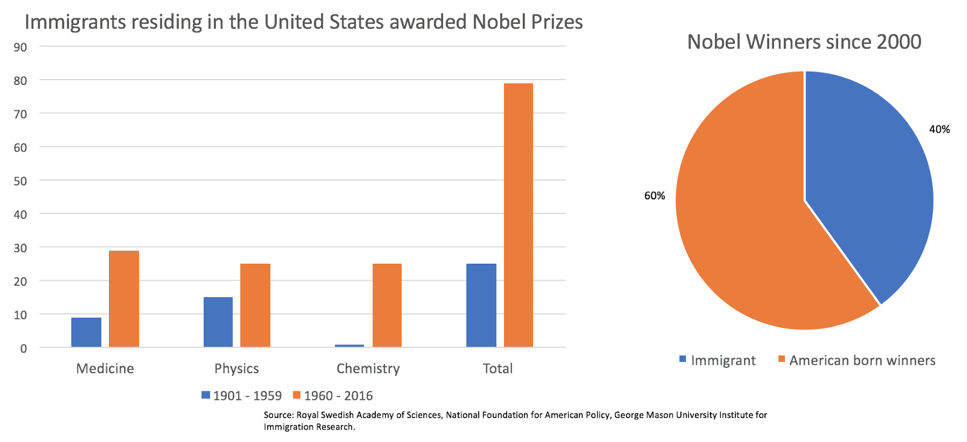

A quick glance at the number of Nobel prizes awarded to residing immigrants before and after policies were passed to indiscriminately welcome the foreign-born:

While there exist many statistics that showcase the contributions of the foreign-born on American soil, some of the more remarkable accomplishments by immigrants have been in medicine and for the US military. Most notably, Abe Karem — the lead behind the highly-feared Predator, America’s oft-used drone in international combats since 1995 — is an Israeli immigrant.

While there exist many statistics that showcase the contributions of the foreign-born on American soil, some of the more remarkable accomplishments by immigrants have been in medicine and for the US military. Most notably, Abe Karem — the lead behind the highly-feared Predator, America’s oft-used drone in international combats since 1995 — is an Israeli immigrant.

On the other hand, a study by the Institute for Immigration Research in 2010 showed that nearly 28 percent of physicians and surgeons were foreign-born. This number is only to become larger in the light of increasing shortage in medical experts, as reported by the Association of American medical Colleges. Biomedical studies, and cancer research in particular, have witnessed the growing role of immigrants. As reported by the National Foundation for American Policy, 42 percent of researchers in the top seven cancer centers are foreign-born. More significantly, they have also been the brains behind studies of chemotherapy, epigenetics, and toxicology.

These momentous contributions have come at a price. Laws and government policies over the past century have regulated immigration with stringent measures, and the contribution of skilled international workers has been substantial only over the past 50 years. Two acts that have played a significant role in changing the landscape of immigration labour, especially aiding scientists and professionals, are:

- 1965 Immigration Nationality Act: This historic act repealed the national-origins quota, which had been in effect since the 1920s. Along with the Immigration Act of 1917, which banned most Asians from entering the United States, the national-origins quota made it significantly difficult for anyone but the Western and Northern Europeans to enter the country.

The 1965 legislation paved the way for restrictions on the number of immigrants from all over the world, particularly from Western Europe. With the introduction of a system based on family relations and skills, the science and engineering community saw a rise in talent from even previously barred nations, as evidenced in the Nobel Prize numbers above.

- Immigration Act of 1990: This law attempted to transition a majorly family-based immigration system to one which accepts applicants with higher skill and education qualifications. The number of visas allocated on the basis of skill almost tripled from 54,000 to 140,000 annually. This quota has been rising each year, with a certain amount also set aside for students with advanced US degrees. Some suggest that this has further attracted talented students to both conduct research at universities, as well as to work in tech companies.

Thus, policies that favor increased skilled labor immigration, when all-encompassing, have shown to have a positive correlation with growth in scientific research.

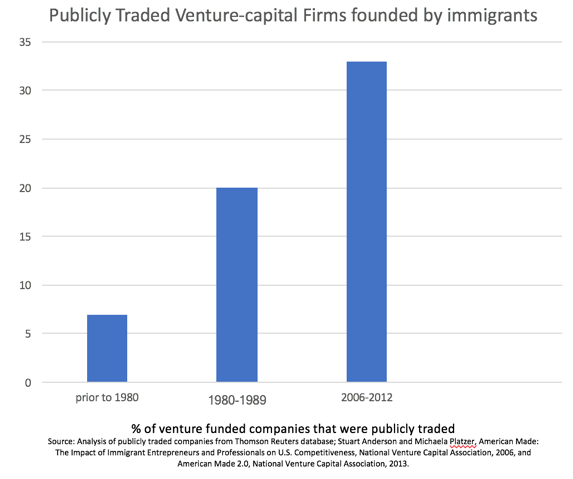

While the scientific method is an integral part of pure science fields like physics, medicine and chemistry, it also defines engineering and technology. In line with the passage of the above immigration legislation, a report by the Public Policy of California has shown that the rate of entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley increased over time, subsequently creating more jobs in the area. The numbers are testament to this trend:

If one looks past these percentages, the names of the companies — Google, Ebay, Facebook, Chobani, Yahoo, LinkedIn, Tesla — ring a bell, and are known as some of the leading firms with significant revenue. All of these have at least one immigrant founder or co-founder and are valued together at $900 billion in market capitalization according to the National Venture Capital Association.

While things have looked up for immigrants over the past half century, consistent appraisal of stricter policies could deter many from coming here. Foreign nationals that seek to reside and work in the United States pass through multiple legal barriers that on average last a couple of years and could for some prolong for 10 years.

The intangible cost of the process to seek citizenship in the United States already being high, adding further administrative checks that lengthen the process would affect the many contributions of immigrants on American soil. Globalization allows immigrants to consider a wide variety of countries, several of which harbor both nourishing work environments and a welcoming attitude to immigrants. Consequently, one doesn’t have to look very far to find greener grass.

While the March for Science is a fight for the pure sciences, the environment, and transparency in policies, it is highly enmeshed with the call for open borders and less paperwork for immigrants, a move which in the past has shown to result in both scientific and economic growth.