No One’s Laughing: “Funny Girl” and an Accountability Crisis

Image credits: Getty Images Illustration Luis Rendon

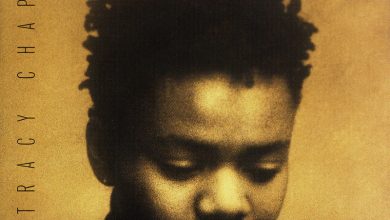

Image description: Broadway Revival Funny Girl posters with Beanie Feldstein and Lea Michele on the front.

To many, the name “Fanny Brice” may sound only vaguely reminiscent of a niche TV show reference from the 2010s, but for others the name is emblematic, weighted with decades of lore and glamorization. Lately, the name has taken on a new meaning as avid broadway and pop culture fans flock the internet to comment on the chaos the role of “Fanny” has become.

Fifty-eight years after “Funny Girl” opened and crowned Barbra Streisand a modern Broadway legend, the show was given its first official revival in 2022. Most golden-age musicals as beloved (yet troubled) as “Funny Girl”, seldom have such a long, nearly sixty-year, lapse before their first revival. Aside from the undeveloped book and its admittedly dated plot line, the delay of an official Broadway revival was due in large part to one thing: finding the perfect Fanny.

Barbra Streisand not only made a name for herself with the role of Fanny Brice in 1964, but her personal performance became inextricably linked to the complicated, hilarious, tear-filled, boisterous character of Fanny Brice. Which is a bit ironic, due to the fact that the role is based off of the real life 1920’s comedienne of the same name. Earlier casting notices for Fanny Brice called for an actress who was a “once in a generation talent.” Filling the shoes of Barbra Streisand in her most iconic role is no easy task, so it’s no wonder the search for the perfect player has led to such a theatrical tizzy. Because, truly, “who could be Bahbruh?” (spoken in the voice of a long island Yiddish Bubbe).

After such a long Funny Girl hiatus, the 2022 revival begs the question,“why now?” Since the resurgence of live theater in September 2021, the theater industry has been forced to address its historically inequitable casting and other overt and subtle racist practices. In reaction to the civil unrest during 2020, the coalition “We See You White American Theater” was formed to demand industry changes on behalf of BIPOC theater makers. Yet in this new age of Broadway that we all hope to usher in, Funny Girl is also a revival of the industry’s most insidious habits.

When Beanie Feldstein was first announced to lead the production, an air of positive potential was cast for the otherwise unhopeful revival. A beloved actress of stage and screen, Feldstein shined in films like “Ladybird” and “Booksmart,” impressed us (and TV critics) in shows like “American Crime Story: Impeachment,” and charmed as Minnie Fay in “Hello, Dolly!”. Not only did Feldstein’s casting stir loyal “Ladybird” fans, but it excited Broadway fans and media as a step towards more authentic and size-inclusive casting. Perhaps, in this new post-pandemic age, Broadway would live up to the open and accepting image it loves to preach. As excitement spread through waves of press about Beanie, Broadway forums also began to whisper about Lea Michele, who has been not-so-subtly promoting herself for Fanny for years.

Beginning to understand Lea Michele’s relationship with the role of Fanny Brice requires scrolling and sifting through nearly a decade of cultural archives. It begins in 2009, when Lea Michele’s “Glee”character, Rachel Berry, sings her rendition of Funny Girl’s act-one-ending anthem, “Don’t Rain on My Parade.” The show’s resounding popularity, and Lea Michele’s starring role, made this song and Michele’s affiliation with this song an unbreachable cultural and theatrical tether. As the TV show went on, Michele performed many other renditions of Funny Girl songs and was characterized as a Barbra Streisand superfan from the very first episode. In the fifth season, her character was even cast as Fanny Brice in a fictional Broadway revival of “Funny Girl:” a very unsubtle prophecy as “Glee” showrunner Ryan Murphy had the rights to “Funny Girl” at the time (and had publicized with Michele his intention to cast her as the lead). Naturally, all eyes were on Lea Michele when a “Funny Girl” revival was rumored, and even more so when Beanie was announced to play Fanny Brice, what surely Michele felt was in many ways a role destined to be hers. Michele, awkwardly and perhaps even defensively commented on Beanie’s casting announced “Yes! YOU are the greatest star! This is going to be epic!” Beanie, when asked about the casting drama that the internet was feasting over, said she had no idea who Lea Michele was or the attachment she had with the show. “I don’t know the woman whatsoever,” she said.

Lea Michelle’s cultural claim to the role, and minorly odd Instagram etiquette, may be overlooked if it weren’t for her notorious reputation as one of the industry’s biggest divas. Her sense of entitlement had been widely rumored and broadly accepted. Her poor manners, high demands, and general diva-like nature were ironically consistent with her character’s personality on “Glee.” Many “Glee” fans know the story that when Lea Michele auditioned for the role of Rachel Berry, as she tells it, “… the piano player skipped through the second verse, so right in the middle of my song, I was like, ‘Excuse me!’ … Very Rachel Berry!” Isn’t it so funny and wonderful when snapping at the piano player gets you the role you want? Michele thought so.

While rumors of Michele being “difficult” were well known, in June 2020 even more serious allegations surfaced. After Michele tweeted in support of BLM after the murder of George Floyd, former “Glee” co-star Samantha Marie Ware (who played Jane Hayward) tweeted in response how Michele made her life “a living hell” and described microaggressions and bullying she faced from the actress. Ware’s tweet sparked many other actors to speak out about the ways Michele had intensely mistreated them. In response, Michele posted an apology (via-Notes app) to Instagram, a good sign of sincerity surely. In this post Michele apologized for the way her behavior “was perceived.” She didn’t take accountability for her actions and, when interviewed later, she refers to her “pressure of perfectionism” as accounting for leaving her “with a lot of blind spots.”

After her HelloFresh sponsorship dropped her and she retreated out of the public eye, Twitter once again put her back in the internet swirl when cycling the conspiracy theory about her being illiterate. Theater-maker and TikToker Katherine Quinn argues that the illiteracy meme let people laugh at Michele instead of hating her. Quinn explains “introducing humor makes something less scary, and inherently less frightening … It almost gives people permission to talk down to her and tolerate her simultaneously.” Somehow making fun of Michele allowed her to re-enter the pop-culture spotlight, if not the stage spotlight itself. Michelle no longer feels the need to lay low, and recently she even posted a TikTok joining in on the joke that she can’t read.

Lea Michele was cast as Fanny Brice in July of 2022, when Beanie Feldstein chose to leave the show after getting lukewarm reviews, (which many attribute to fatphobia). Despite the laughs the twitter sphere had in Lea Michele’s jest, the internet did not forget her wrongdoings. Upon Michele’s “Funny Girl” casting announcement, Samantha Ware, who’s original tweets had stirred the many outcries against Michele in 2020, tweeted “Yes, I see y’all. Yes, I care. Yes, I’m affected. Yes, I’m human. Yes, I’m Black. Yes, I was abused. Yes, my dreams were tainted. Yes, Broadway upholds whiteness. Yes, Hollywood does the same. Yes, silence is complicity. Yes, I’m loud. Yes, I’d do it again.” And Ware isn’t the only one who recognizes the Broadway industry’s re-submergence into dated and oppressive ambivalence.

There’s an unspoken sense that Lea Michele is just so good that this in some way licenses her otherwise unacceptable actions. But what’s a large part of what makes her “so good” to modern theater-goers and critics, is the way she fits into our idea of the ideal Broadway star, who is a size 2 or 4 and sings a strong belt. If these weren’t our rigid ideals, if we were more creative and accepting with how we viewed actors’ value and potential (not to mention with how we viewed beauty), the sense of objectivity and the authority of “star power” wouldn’t grip nearly as strongly.

For decades producers and agents have enabled “the diva” star personality: the stereotype of all the idiosyncrasies and specialty dressing room requests. But allowing that sense of privilege and entitlement extends beyond the dressing room, and is folded into allowing the sort of entitlement that breeds bullying at its most docile and racism at its most insidious. Holding people accountable for their actions goes beyond racially charged comments (though those are obviously extremely important) but to the basis of how you treat those around you: especially in theater and entertainment, an industry that is so rooted in vulnerability.

But just as the entertainment industry is rooted in the vulnerability of artists and creatives, it, like most else, folds to the almighty dollar. Broadway is an industry that is inherently capitalist, and Broadway executives enable “the diva” because the diva sells. “Funny Girl”’s sales were dipping and Lea Michele, all personality questions aside, would sell tickets. While onlookers can blame the executives (and blame we shall), aren’t we still buying tickets? It’s a question of priorities on the part of the producers, but also on the consumers as well. With shared responsibility, consumers decided to let Lea Michele come back.

In the midst of social unrest of 2020, Broadway industry executives were forced into conversations regarding creating more opportunities for diversity, equity, and inclusion within the theatrical spheres. Yet, as “Funny Girl” has shown, Broadway’s inappropriate systems and structures continue to be upheld and reaffirmed. What will it take for these abusive and inequitable systems to change? Will revenues have to nosedive for producers to look up? How will the next generation of theater-makers and producers usher in an age of accountability instead of “funny” girls and financially-focused affairs?