The Antithesis of the Media’s Idea of Healthy Living

Image description: An 8-pack of Oishii’s Omakase Berry is on a table with a yellow plaid tablecloth.

It is May 2020, the heat of quarantine, and the U.S. has just descended into chaos: the SAT has become irrelevant, celebrities are doing “Imagine” by John Lennon sing-alongs, and TikTok screen time is at an all time high. And after rotting in your bed binging Netflix for two months, it hits you that now is your chance for a glow up. So you start eating avocado toast everyday and fantasize about returning to school post-pandemic with a six pack. Every afternoon, you unroll a yoga mat onto the floor of your room and pull up a “Chloe Ting 10-Minute Ab Workout” video on your laptop. After the workout ends, you check yourself out in the mirror and you think to yourself, “I think I can see the abs already.”

Chloe Ting, like many others on today’s social media platforms, is a self-proclaimed “gymfluencer,” leading a seemingly empowering movement toward fitness. This broadening fascination with health has been on the incline as modern media constantly evolves to broaden its range of influence. YouTubers upload “What I Eat In a Day” videos, actors spend 3 hours daily with a personal trainer to burn fat for their big Hollywood break, and celebrities are going on diets consisting solely of baby food.

And although, yes of course, it’s super important to be conscious of one’s diet and exercise routine, the glamorous lifestyles of celebrities and fitness influencers who upload diet videos actually promote capitalistic and consumerist practices. Diet culture and healthy lifestyles require a high disposable income to fund the tools necessary to achieve an idealized well-being.

On its most fundamental level, being healthy necessitates having a balanced diet with sufficient calories, proteins, minerals, and vitamins. However, lower income populations are typically overlooked in urban planning processes because of their lack of expendable money. In a consumerist world that favors big spenders, poorer neighborhoods consequently receive the short end of the stick when it comes to accessibility to healthy resources. Food deserts epitomize this startling discrepancy: low income areas that have limited access to healthy and affordable supermarkets. Organic and freshly harvested groceries that adhere to media-popularized vegan or vegetarian diets are pricey and difficult to access for those trapped in food deserts.

Erewhon, a California luxury supermarket, is a favorite amongst celebrities as it boasts niche, locally produced foods that are specifically curated for individuals on alternative diets. Kanye West even tweeted about the staple “Erewhon drip” (referring to the designer athleisure worn by celebrities on their off-days) and paparazzi would set up shop there pre-pandemic to capture celebrities like Leonardo Dicaprio and Dakota Johnson in their natural habitats. And since the groceries it supplies are of supremely high quality, Erewhon works in favor of privileged clientele with its exclusive prices. In fact, if there existed a hierarchy of grocery stores based on quality, Erewhon would claim its position at the very top. I mean, where else would you be able to buy $19 elitist vegan coconut yogurt and blood-red immunity-boosting lung tonic that screams: “You’re not in my tax bracket?”

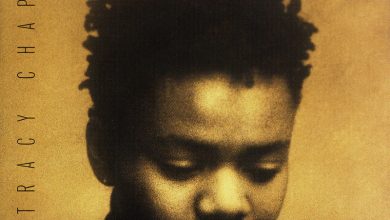

In addition to promoting highbrow grocery stores, popular culture overemphasizes health practices that are exclusive to the rich. Take the Omakase berry for example: a rare type of strawberry cultivated in the Japanese alps and is marketed to be “always clean and always ripe.” Accordingly labeled as the “Tesla of strawberries,” the high-tech Omakase berries are sold in packages of 8 for $50, upending the produce market and reinforcing the inaccessibility of more nutritious food options. To make matters worse, Oishii, the company behind the Omakase Berry, has been featured in Time, The New York Times, Forbes, and even influencer Emma Chamberlain’s Instagram story. Its features in social media perpetuates exclusivity even in the most basic day-to-day necessities and a domineering consumerist culture. Even if Oishii may be working to transform the food industry, its normalization of a $6-per-strawberry price point has an indirect and absurd impact on food instability.

And although we are still in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic right now, we must remember the pandemic that was #FitTea on Instagram in 2016. The misleading claims of these concoctions included a long list of supposed health benefits such as thinness, unclogging arteries, and an end to all migraines. And even though there was no scientific evidence to support these assertions, celebrities with millions of supporters like Cardi B sponsored these so-called health products. It’s a good marketing strategy: when famous people with perfect bodies claim to have done a 14-day FitTea detox to get toned, their fan bases will surely follow. But the truth is that these celebrities have easy access to plastic surgeons and other expensive outside tools to create a facade of perfect health, and weight loss profiteering is engineered to use influencers to take advantage of the common populace. Unfortunately, the basis of FitTea and other “detoxing teas” was rooted in making a quick buck off of impressionable youths’ superficial insecurities, and there really does not exist a simple tea that can be brewed to give you a flat stomach and hourglass figure.

Furthermore, the vegan and alternative diets that many celebrities and influencers endorse are also intricately embedded in modern cycles of poverty and ill health but uphold a facade of glamor and allure. “Clueless” actress Alicia Silverstone advocated for veganism in an interview with vegan blog LIVEKINDLY: “Now it’s actually cool to be vegan and immensely valued from a health and environmental standpoint.” Although Silverstone is correct in veganism’s sustainability benefits, she completely overlooks the financial accessibility of vegan diets and instead favors their superficial consumerist value. In addition to Silverstone, there also exists an entire division of celebrities that advocate strongly for veganism, calling for their fans to change their diets and renounce animal-based products to “save the environment.” They collectively paint the picture of a united world under veganism and imply that participating in an alternative diet is easily achievable.

In actuality, veganism is much more expensive and therefore inaccessible than traditional diets. Because it is still a relatively small market, vegan food suppliers and retailers are not as well-established and resourceful as meat and poultry industries. The consistent high demand of meat increases meat farming and consequently drives meat prices down; large government subsidies that fund meat consumption also play a huge role in the price discrepancy. The lower demand for vegan food contributes to its exclusive quality and drives up prices, therefore decreasing its attainability to the general populace. To put things into perspective, you would be able to purchase 2 whole pounds of ground beef with $6 at the supermarket, but that same $6 would only permit a vegan to 2 plant-based meat patties.

In fact, this idea that “Anyone can go vegan or keto if they really try!” correlates with the toxicity of the bootstrapping myth, as it maintains the narrative that if poor people simply work harder, they could be just as wealthy as the top 1%. In reality, this perspective is beyond impractical and borderline delusional, as generational wealth and institutionalized cycles of poverty build cages designed to make poor people poorer and rich people richer.

Bootstrapping conveyed through alternative diets emphasizes the concerningly influential role that capitalism plays in overall well-being. Working-class individuals lack the time to research and ration out what food they can or cannot eat when they are struggling to even provide for their families. In extreme cases, fitness and wellness are not even a priority in their daily lives simply because of how difficult it is for them to make enough money to afford basic necessities, let alone gym memberships and organic groceries from Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s.

So let’s face the facts: healthy lifestyles favor the rich. As these nuanced diet and wellness practices are romanticized and popularized in the media, they prove themselves to be only accessible to those with a disposable income. Whether it be through Chloe Ting ab workouts or crazy celebrity diets, most popular wellness movements contain undertones of privilege that warp the idea of health into something to be marketed in an excessively consumerist nature. Trends that are supposed to encourage universal well-being actually pose unrealistic standards to lower-income populations, spreading the message that only wealthy people deserve to be fit and healthy. That’s not to say that following health trends on social media is detrimental to oneself; rather it is important to stay conscious of the cycles propelling it.