The Commodification of Self Care

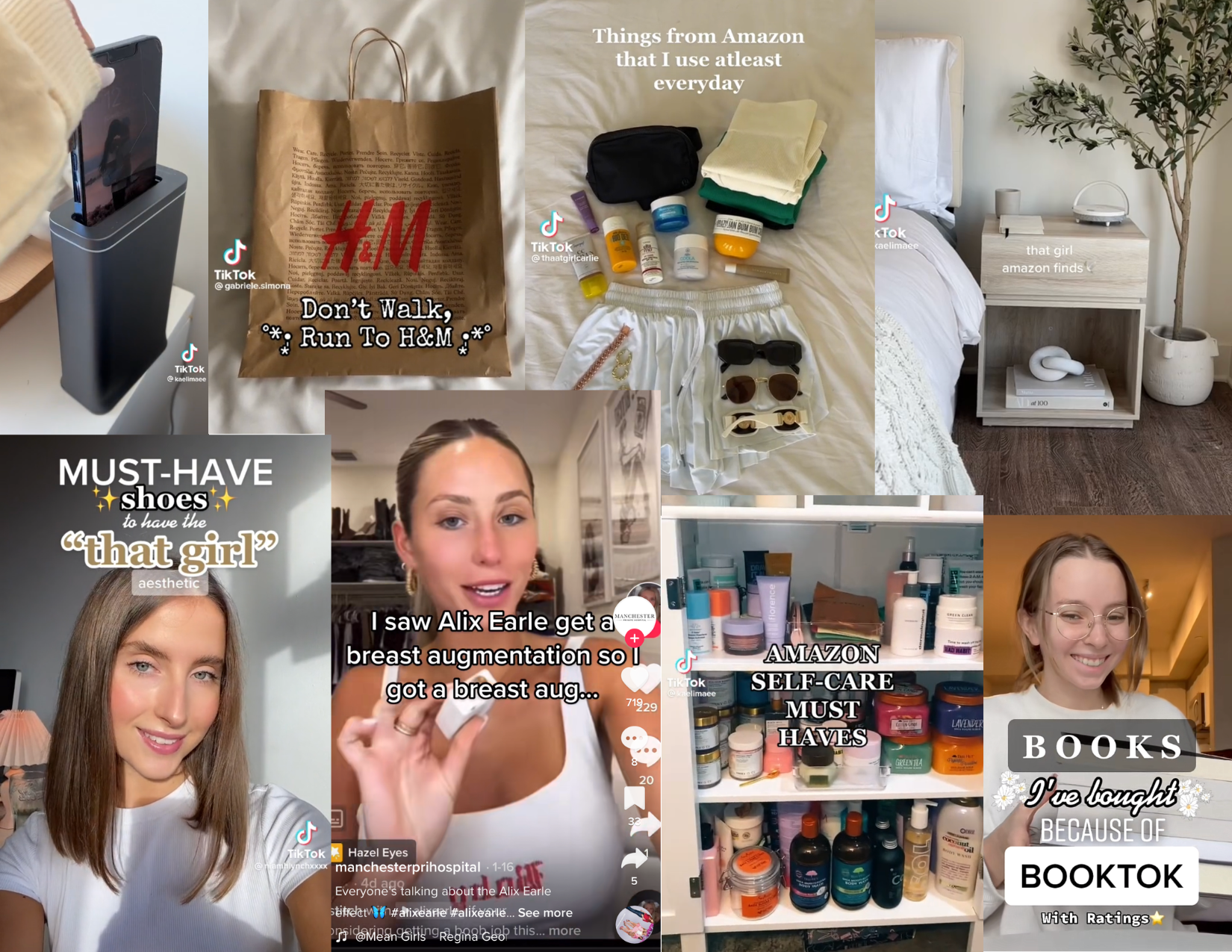

Image description: The collage consists of screenshots from TikToks found under #selfcare and #thatgirl. Top row from left to right: Inserting iPhone into phone sanitizer; “Don’t walk, Run to H&M” with an H&M shopping bag; “Things from Amazon that I use at least everyday” with a compilation of miscellaneous daily items”; “That girl Amazon finds” thumbnail. Bottom row from left to right: “Must-have shoes to have the ‘that girl’ aesthetic” thumbnail; “I saw Alix Earle get a breast augmentation so I got a breast aug…” with a background of influencer Alix Earle; “Amazon self-care must haves” with a photo of a fully stocked cabinet of skincare; “Books I’ve bought because of #BookTok with ratings” with a girl holding a stack of 6 books in the background.

Image Credits: Collage made by Amber Phung. Collage consisted of screenshots from TikToks by the following listed creators: top left to right: @kaelimaee, @gabriele.simona, @thaatgirlcarlie, @kaelimaee; bottom left to right: @niamhlynchxxxx, @manchesterprihospital, @kaelimaee, @isabellagerli

Had a difficult day at work? Bombed a midterm you thought you aced? Bae not texting you back? Struggling to find a silver lining in this perpetually downward spiral we call life? No problem… Take a hot bath. And don’t forget to toss your towel in a $180 towel warmer so that you’ll be shrouded in warmth the second you step out! Put on a face mask and massage your cheeks with a gua sha to sculpt that jawline. Lather your body in a $48 scented body cream (not body lotion because that’s not nominally bourgeois enough). Apply that expensive 10-step skincare routine that you spent hundreds of dollars on at Sephora. Put on your matching pajamas to appeal to the inescapable male gaze that overshadows the feminine experience. Float over to your fluffy $6000 cloud couch in your living room. Turn on your massive widescreen TV & watch your favorite TV show while simultaneously scrolling through Instagram and eating a vegan, gluten-free, paleo, keto snack from Erewhon. As a little bonus, you can order clothes for yourself too – maybe an Aritzia dupe from Amazon! Oh, and don’t forget to film it all to upload to TikTok. Feel better now?

This absurdly extravagant regimen has, in recent years, become conflated with self care. The rise of TikTok and Instagram influencers as dictators of style has drastically transformed the landscape of contemporary fashion and lifestyle trends. The haphazard incorporation of “self care” into social media has overshadowed the activist roots of the term, and instead morphed self care into a paradigm of excessive consumerism.

Refer to the “TikTok made me buy it” trend, of which videos have amassed over 7.4 billion views to this day. In these videos, users – often unsponsored by any brands – show off the miscellaneous products they buy, ranging from a sweater to a set of bedsheets. Often captioned with the phrases “You need this in your life,” “Don’t sleep on *giant multimillion company*,” or “Run, don’t walk, to buy this,” these TikToks epitomize overconsumption at its peak. And the users who are feeding into this perpetually burgeoning cycle are rarely aware of the toxic principles they’re reinforcing.

Beyond the bubble baths and expensive facials that characterize today’s so-called self care routines, there lies a more radical history that many of us are probably unaware of. The term “self care” was first coined in the 1950s to describe how institutionalized patients could heal through acts of care and empathy. Within the medical ethics community, self care became regarded as an alternative form of treatment to increase a patient’s self worth.

Then, when the Civil Rights Movement originated in the 1960s, self care became a core foundation of community connection within the Black Panther Party. In this context, self care was politicized and broadly popularized. Trailblazing Black Panther leaders Angela Davis and Ericka Huggins employed mindfulness techniques like yoga and meditation when they were falsely charged and incarcerated for the murder of an FBI informant. After their release, they began promoting the benefits of nutrition, physical activity and interpersonal relationships while navigating a rapidly changing, complex society. The Black Panthers later integrated self care into its framework to emphasize the holistic health of the Black community in times of racial struggle: applying it to medical care, food security, child care, banks, and many other ways of taking care of one another beyond institutions built to exclusively serve white people.

The origin of self care derives from minority efforts to care for their community and work within a system that systematically mistreats them. Yet, modern notions of self care have completely strayed from mental nourishment, shifting towards capitalism and excessive consumption instead.

With the rise of online marketing and branding, today’s economy is merely a slew of corporations racing to create the most user-friendly campaigns to boost profits to an all-time high. Instagram and Facebook Marketplace were just precursors to the giant capitalist machine that is TikTok. In fact, TikTok itself has characterized its “retail path to purchase” as an “infinite loop”: user generated content and personalized algorithms ensure that anyone scrolling will inevitably stumble upon something they’d want to purchase.

See Alix Earle for example. A senior at UMiami, Alix blew up in late 2022 when she doubled her TikTok following from 1 to 2.2 million through her “Get Ready With Me” vlogs. Her seemingly genuine and down-to-earth nature boosted her to many For You Pages, and within a matter of weeks, beauty products and trends began to be named after her. White eyeliner on the waterline became “Alix Earle eyeliner”; her video promoting the Mielle Organics Rosemary Oil made the product sell out in stores in less than a week; the same happened with the Drunk Elephant Bronzing Drops (re-dubbed the “Alix Earle Bronzing Drop Hack”); when Alix used the filter “Blue Eyes” on her videos, many other users began calling it the “Alix Earle Filter.”

And even beyond influencers like Alix Earle, there still exists extremely successful TikTok marketing from UGC. Because of the fact that a TikTok about anything can go viral, users often don’t even need to be sponsored or particularly famous to get millions of views and sell out a product. All it takes is one lucky video.

Moreover, TikTok’s influence on commodities extends even after the purchase has been made. I’m sure that you’ve seen the “BookTok” shelves at Barnes and Noble, stacked with Colleen Hoover, Adam Silvera, and Ottessa Moshfegh. The unboxing content, tutorials, and videos taglined “Books that made me cry” or “Books I couldn’t put down” spread like wildfire and build a community of users who continuously subsist off Amazon storefront links and quick purchases.

The reinforced popularity of certain commodities forms a type of in-group that has the trendiest clothing, the cutest jewelry, this particular blush, and that Madeleine Miller book. The exclusivity that is inadvertently engendered by this group urges the out-group to feel like they’re missing out on something, like all their friends are in a group chat without them.

This clique-ish nature enveloping TikTok consumerism extends to the concept of self care. TikToks labeled “Things I bought to elevate my self care” are painfully ironic, as the mere likening of spending money to nurturing oneself is oxymoronic. How will having a $38 lip balm remedy your mental struggles? Conversely, it implies that without these so-called ‘self care’ products, you’re doing something wrong. Oh, so you’re not taking care of yourself enough? Just buy more stuff.

This oversaturation of retail therapy has greatly warped the meaning of self care. It encourages us to turn to quick, easy, and temporary solutions to problems that could be long term. And with social media’s obsession with being “aesthetic,” there exists an increased emphasis on the way things look rather than the meaning or connection we have with them. Thus, people obsess over what they have in a hollow, materialistic way, merely focusing on having a flashy, glamorous display of commodities. In doing so, an addictive cycle of anticipation and reward is reinforced by impulsive, emotional purchases – the antithesis to the mental nourishment that self care calls for.

Commodity fetishism, introduced by German sociologist Karl Marx in his book “Capital: A Critique of Political Economy,” perfectly depicts this separation of the individual and their commodity within capitalist society. Marx states that there is a severe cultural and psychological impact of living in a commodity-centered world: it allows consumers to blindly treat products as magical objects with somewhat mystical qualities. Buyers perceive commodities as existing ‘out there,’ just stocked in store aisles or conveniently accessible on Amazon; but rarely as products of human labor and passion. Instead of spending time with people we love and care about, we turn to the online marketplace, where you can order anything with a couple clicks and have it magically appear on your doorstep in 3-5 business days. The illusory nature of commodities within our swiftly modernizing world further depersonalizes commerce, as it removes face-to-face interaction with the individual worker and instead suggests that commodities simply surround us in an abstract fashion.

So when an alleged self care “guru” makes a TikTok with products that supposedly boost self care linking to an Amazon storefront, there stands a stark (and somewhat disrespectful) contradiction to the radical history of the practice. The processes – or more like products – that comprises contemporary concepts of self care are driven by an unabating dehumanization of the worker and the consumer.

And what’s even more ironic is that at the end of the day, none of this stuff actually achieves the goal of ‘self care.’ Buying those trendy mini Ugg platform boots or that really cute Lululemon BBL jacket isn’t going to make you feel more confident and fulfilled. Sure, the initial burst of excitement feels good, but it may just leave you feeling worse – when the novelty of your purchase wears off, the sense of deficiency will return once again.

You can find so many alternatives to spending money that’ll give you more happiness than adding stuff to your cart ever would. There are a multitude of ways to take care of yourself that don’t require spending exorbitant amounts of money – listening to your favorite music, spending time with your friends and family, or doing some yoga or meditation. Of course, this isn’t to say that you should stop buying stuff entirely. Instead, it’s just about finding the perfect balance between overconsumption of retail therapy and self care.

The commodification of self care has completely removed the individual from its historically intellectual and spiritual practices. In reality, self care is so much more than indulging in materialistic desires. Rather, we can honor the powerful history of self care by spending time with loved ones and investing in activities that actually matter to us. While it’s fun to go online shopping, think twice the next time you click on a link to buy a “holy grail” skincare serum or that “must-have, closet staple” Skims dupe. Ask yourself if you’ll really feel better from that quick and easy purchase, or if you’re merely falling prey to the infinite loop of consumerism.