The Mad Witch in the Multiverse

Image Credits: Marvel

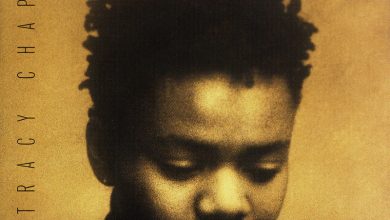

(IMAGE DESCRIPTION: A still from the 2022 film “Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness,” featuring Elizabeth Olsen (center) as Wanda Maximoff/The Scarlet Witch. Olsen is wearing a red and black bodysuit with black boots, a red-haired wig, and a russet-colored crown, sitting cross-legged as she levitates in the center of the room. Surrounding her is a circle of burning candles, all in different shapes and sizes, illuminating an ominous room bathed in low, red lighting composed of bricks and ancient statues.)

(CONTENT WARNING: The following article contains spoilers for “Marvel Studios’ Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness,” as well as a discussion of sexism, ableism, mental health, suicide, and bad-faith discourse.)

There’s a lot going on in “Marvel Studios’ Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness,” and I do mean a lot.

Not only is Benedict Cumberbatch reprising his role as Doctor Stephen Strange, the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s resident (ex-) Sorcerer Supreme, he is also playing multiple versions of the character, including the one that’s a gross looking zombie. There’s also a number of highly-anticipated cameos from fan-favorite actors and characters, such as Hayley Atwell’s Captain Carter, the super-soldier version of Peggy Carter from Marvel’s timeline-bending animated series “What If…?” and Sir Patrick Stewart’s Professor X, whose MCU variant is a cross between the Professor X of the “X-Men” films and the Professor X of the 1992 animated “X-Men” series. “Multiverse of Madness” also marks the introduction of Xochitl Gomez’s America Chavez, a teen Puerto Rican heroine who has been drawn as darker-skinned in the comics but has undergone an Aunt Viv-ification (read: colorist) for her live-action cinematic debut. It’s also worth mentioning that America is an out lesbian in the comics, but “Multiverse of Madness” reduces her lesbian identity to a Pride flag pin on her acid-wash denim jacket. Oh, and there’s something about a multiverse on the verge of collapse squeezed in here, somewhere.

Needless to say, this movie has (do your best Stefon impression… now!) everything… and almost none of it works. Despite director Sam Raimi — the man behind the beloved 2000s “Spider-Man” trilogy and the 80s/90s cult horror “Evil Dead” trilogy — injecting nearly every frame with his signature blend of humor and horror, “Multiverse of Madness” is a disappointing mess lacking a clear, narrative goal beyond setting up a scattershot multiverse gimmick as a major future franchise element audiences must care about. Of all the maddening and underwhelming elements screenwriter Michael Waldron crams into this movie, however, no element is as egregious as the treatment of Wanda Maximoff.

“Multiverse of Madness” marks Elizabeth Olsen’s return as Wanda, who fans last saw in the Disney Plus limited series “WandaVision.” Within the span of nine episodes, “WandaVision” offered an imperfect but nuanced, mature, and careful depiction of trauma, grief, and mental health that moved Wanda into a freeing space beyond the role of heroine, villainess, and anti-heroine. But “Multiverse of Madness” sets Wanda back in the worst way possible. It took six years and a limited series for Marvel Studios to finally christen Wanda with her comic book codename ‘The Scarlet Witch,’ but “Multiverse of Madness” sullies both the name and Wanda’s character in two hours and six minutes.

When We Last Saw Wanda Maximoff…

As Sam Raimi promised, “Multiverse of Madness” gives the fans what they wanted, but not in the way they expected. The trailers teased Wanda as an ally to Strange, someone he seemingly turns to upon realizing this multiverse issue is too big for one magic user to handle. When Strange approaches her in the first teaser trailer, Wanda isn’t necessarily happy to see him, nor is she angered by his presence. “Well, I knew sooner or later you’d show up,” Wanda calmly says. “I made mistakes, and people were hurt.”

Those “mistakes” Wanda made and the “people” she hurt is in reference to “WandaVision.” In a moment of mental distress, Wanda unexpectedly casts a magical bubble – aptly called “the Hex” – that turns her reality into a fantasy world closely modeled after the classic (and mostly white) American sitcoms she consumed in her youth. In the Hex, Wanda became an all-American housewife living a life of domestic, suburban bliss with her beloved Vision and their twin sons Billy and Tommy, while the citizens of Westview were re-imagined as background extras. Worse yet, fans later learned Westview’s denizens were forced to psychologically endure the horrific trauma and anguish Wanda had experienced in the MCU thus far.

“The townspeople’s lives are disrupted,” writes Eric T. Styles in his review of the series, “sharing Wanda’s nightmares, experiencing in their sleep the very terrors that plague her. They are stuck in her creation, suppressed “flesh puppets,” as one character describes them. The warmth of their smiles and the innocence of their comedic antics hide a crippling truth from Wanda: that her attempt to escape trauma is traumatizing others.”

This disturbing element of the series led to an uncomfortable but understandable question being raised: is Wanda Maxmioff the villain of her story?

“WandaVision” didn’t totally think so. Characters like all-powerful elder witch Agatha Harkness (who actively exploits Wanda’s powers and ill mental health for her own nefarious purposes) and S.W.O.R.D.’s callous Acting Director Tyler Hayworth (who deliberately paints Wanda as a hysterical woman and a terrorist to motivate agents to apprehend her so S.W.O.R.D. can use her power) are the real villains, but that doesn’t erase the fact that Wanda hurt the people of Westview, even if it was accidental. As Comic Book Resources’ Alexander Sowa writes, ‘WandaVision’ made a deliberate effort to bring Wanda to a place of villainy, but never actually [made] her the villain.” For much of the series, “WandaVision” creates a mystery surrounding the Hex and what caused it, but once we learned Wanda had created the Hex that’s traumatizing an entire town of innocent people, it makes sense why some see Wanda as a villain. (It also doesn’t help that the series finale makes the baffling choice to let Wanda apologize to one major character rather than the citizens of Westview at large.) Given that “WandaVision” ends with Wanda flipping through the pages of the evil grimoire known as the Darkhold, it is easy to see how some folks landed on the conclusion that Wanda Maximoff is, once again, a villain.

Yet, “WandaVision” refuses a neat-and-clean designation for its protagonist. “Wanda is a woman filled with paradox,” Styles writes. “Her creations show the immense power of her imagination and are rooted in a desire to set the world right—even if it is in her own image.” Sowa echoes a similar sentiment: “She’s left a morally complex character, having harmed plenty of people but with little permanent impact. She doesn’t kill en masse, and the collateral damage she causes is mostly psychological damage and trauma. She is guilty, but only of crimes the audience can understand and forgive.”

But, alas, rarely does the Internet forgive, let alone understand. The admittedly baffling creative choices made in “WandaVision’s” series finale yielded a “discourse” that vilifies a character struggling with ill mental health.

In the series’ eighth episode, “Previously On,” we learn Wanda did not intentionally set out to mind control an entire town to act out folksy homages to “Bewitched” and “Modern Family.” Instead, while under severe psychological duress, Wanda unleashed the full might of her powers to create the Hex. The episode deliberately depicts this moment as intensely painful and rooted in sadness and pain. (It must be noted, however, that, although the mystery surrounding the creation of the Hex does obscure her culpability for much of the series, it does not absolve Wanda from taking responsibility for the psychological and emotional pain she caused, something “WandaVision” creator Jac Schaffer pointed out in her appearance on “The Empire Film Podcast.”) Yet, that didn’t stop the stream of cruel memes about Wanda’s intense response to her repressed trauma and grief.

“Shouldn’t vibrator repair be guaranteed for avengers? They saved the world, make sure they’re happy,” read one screencapped tweet in response to an initial tweet that said, “Now who hasn’t gone a lil crazy and done something they regret after their vibrator stopped working when you needed it most???” Another screencap tweet I saw, compiled in an Instagram thread, reacted to Wanda’s “you break the rules” line in the movie with this: “She enslaved Debra Jo Rupp [who plays one of Wanda’s neighbors in “WandaVision”] for a walking iPhone.”

Navigating digital spaces as someone living with ill mental health is never easy, but the casual cruelty and sexism that I saw online after “WandaVision” and, now, “Multiverse of Madness” was deeply unsettling. If this was how people were responding to a fictional character struggling with mental illness, imagine how they treated real human beings enduring the same challenges. (Now, before you say, “Girl, it’s not that deep,” I’mma let you finish but it absolutely is – even if it’s unintentional. How we react to fictional characters, specifically ones who come from intersecting, marginalized backgrounds – e.g. race, ability, gender, sexuality, and class – can reflect real biases and prejudices we may not truly aware of and have never been challenged to unlearn.)

Moreover, the rancid hot takes reminded me of the infamous 2005 storyline “House of M,” penned by influential comics writer/creator Brian Michael Bendis. In the famous storyline, Wanda has an emotional breakdown after losing her children, and her mental distress forces a number of heroes to weigh whether killing her before she harms someone is the best option. The Avengers and the X-Men schedule private meetings to discuss the matter, which is not unlike the Illuminati of Earth-838 (not to be confused with the Illuminati that consists of magical alien lizards disguised as celebrities) coming together in an Ayn Rand-inspired chamber to play judge, jury, and executioner over the fate of Strange and America in “Multiverse of Madness.” In a biting quip that calls out the unnecessary brutality of it all, Spider-Man – the only hero uncomfortable with holding Wanda’s fate in his hands – asks, “So, like, if any of my powers wig out on me, I can count on you to just kill me?”

Although heroes gathering to make tough decisions in the wake of one of their own breaking bad is not a new thing in comics, it is unsettling to see the peers and allies Wanda considers to her family deciding she indeed is too dangerous to stay alive and must be killed at all costs. Couple this with the fact that “House of M” is really just a Wolverine story that renders Wanda a plot device without agency and her mental state a footnote when it is not leading her to go on a magical rampage, and the comic’s treatment of mental illness leaves a quiet but significant impact on Wanda’s character in the seventeen years since it was first published.

It can be seen in the memes that degrade Wanda, ridiculing her experiences of womanhood and her genuine desire for happiness, love, and family. It can be seen in the articles that demand “justice” for Westview’s hurt citizens, but equate punitive punishment as “real” justice. Most importantly, it can be seen in “Multiverse of Madness,” which pits Strange against an all-powerful woman lacking control of her mental state.

In contrast, ‘WandaVision’ rejects the same ableism and vilification of mental illness that “Multiverse of Madness” embraces, offering a nuanced depiction of a woman struggling under the weight of prolonged, repressed trauma. Phase Four of the Marvel Cinematic Universe has made mental health and grief recurring motifs in its stories, from limited Disney Plus series like “Moon Knight,” “Hawkeye,” and “The Falcon and the Winter Soldier” to cinematic adventures like “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” and “Black Widow.” However, ‘WandaVision’ remains the one Phase Four project that acknowledges the full scope and scale of their protagonist’s trauma. (“Moon Knight,” though not without shortcomings, comes pretty close with its active commitment to a respectful depiction of Dissociative Identity Disorder.)

Yet “Multiverse of Madness” deliberately squanders that work in favor of trying (and failing) to elevate its incoherent and irritating multiverse gimmick into an important future franchise element.

The Scarlet Witch, Interrupted

In her aforementioned first scene in “Multiverse of Madness,” Wanda’s explicit acknowledgment of her actions in Westview initially reads as a play to get those spurned by “WandaVision” back on Wanda’s side for the movie. Moreover, Wanda’s facial expression upon seeing Strange approaching her reads less like indignance and more like acceptance. As if she knew this day was coming.

Yet, Strange has no intent on punishing her. “I’m not here to talk about Westview,” he assures, much to Wanda’s surprise. In fact, Strange points out that Wanda did the right thing by taking the Hex down before anyone else got hurt.

At first glance, Strange’s words seem to set up a redemption arc for Wanda. Maybe, by the end of the movie, Wanda would be able to prove Agatha wrong and transform her ominous destiny as the Scarlet Witch into a heroic one. By the end of the scene, however, Wanda slips up, revealing she knows about America Chavez and her power to create star-shaped, interdimensional portals anyone can travel through. (Trust me, it’s way cooler in the comics than in the movie.)

And just like that, the lowkey, sad cottagecore girl facade is replaced with sinister images of red, swirling clouds and scorched earth. Wanda swaps her comfortable citizen disguise and dons her Scarlet Witch robes and crown. Given that ‘WandaVision’ ended with Wanda hearing her frightened boys calling out to her somewhere within the vast multiverse, courtesy of the Darkhold, the villain arc essentially writes itself. But this heel turn feels forced, a move seemingly geared toward the folks who like to spew sexist memes, hot takes, and think pieces disguised as ‘opinions’ about ‘WandaVision’ into the digital ether.

“Multiverse of Madness” unveils Wanda Maximoff as the most dangerous villain Strange has faced to date – and, on paper, it is not a bad idea. Depending on how you interpreted the final minutes of ‘WandaVision,’ Wanda becoming a villain was inevitable, and if you factor in how often Wanda has been treated like an outcast within the Avengers (For example, Tony Stark seemingly hinted that it is Wanda’s fault the Sokovia Accords were drafted and ratified in the first place during “Captain America: Civil War”), it makes sense that she’d grow tired playing a game she’d never win. Moreover, Wanda and her “Chaos Magic” not only makes her one of the MCU’s most powerful beings, but also puts her on equal footing with Strange, a reliable sorcerer capable of holding his own against any powerful being, Thanos included.

In the hands of another writer, “Multiverse of Madness” might have pulled this off. It would have marked the beginning of Wanda Maximoff’s villain era, and I would have enjoyed every minute of watching Wanda magically outwit and outmaneuver Strange at every corner. In fact, some of the best moments in “Multiverse of Madness” came from Wanda; the best horror-centric parts of the movie involved the Scarlet Witch’s embrace of the darker side of her Chaos Magic, which was amplified by her use of the Darkhold. In a vacuum, I really enjoyed Wanda breaking bad and outdoing Strange on his turf. “Multiverse of Madness” does prove once and for all that Wanda Maximoff is indeed the strongest Avenger. (Sorry, Thor.) Unfortunately, Michael Waldron wrote this movie, so it is difficult to fully embrace the beautifully campy horror of Wanda’s turn to the dark side. Waldron is responsible for how woefully inauthentic and problematic Wanda’s villain turn feels, so it is hard to simply enjoy the Scarlet Witch going full Anakin Skywalker.

In the hands of another writer, “Multiverse of Madness” could have framed Wanda’s desire for America’s powers as a devastating effect of the Darkhold’s corruption on her. Maybe the Darkhold would have warped Wanda’s desire to be reunited with what she has lost time and again into the pained cries of her sons. Maybe Wanda and the Darkhold could have been embroiled in a battle of mind, spirit, and power, forcing the former to question whether murdering a teenage girl and stealing her powers would give her the happiness and stability she craves. And since Sam Raimi has plenty of experience making movies about poor, unfortunate souls who come across books of ancient evil, “Multiverse of Madness” would have felt like a warm welcome back to a filmmaker who cut his teeth in the horror genre before upgrading to superhero movies. Unfortunately, Michael Waldron wrote this movie, so the disturbing psychological effects of the Darkhold are ignored because this inane multiverse concept is just that damn important. By half-heartedly pinning Wanda’s sudden evil on the Darkhold, “Multiverse of Madness” repeats Marvel Comics’ worst mistake by robbing the audience of any insight into Wanda’s mental state post-“WandaVision” and robbing the character herself of any agency in a story that essentially revolves around her and the havoc she is wreaking.

In fact, the most insight we get about Wanda’s mental state in her first appearance in “Multiverse of Madness” is distilled into this tense but irritating exchange:

“Wanda, your kids weren’t real. You created them using magic.” Strange says, effectively relieving the viewer from taking Wanda’s pain seriously (and from feeling guilty for seeing her as a crazy, super-bitch).

“That’s what every mother does.” Wanda replies cooly.

In one throwaway conversation, “Multiverse of Madness” not only ignored the thoughtful and empathetic work “WandaVision” put into reinventing Wanda Maximoff, but it also embraced the comics’ infamous tendency to reduce the Scarlet Witch to an all-powerful woman who goes off the deep-end because… motherhood.

A (Hysterical) Mother’s Love

Before I go any further in this section of the article, I want to make a couple things clear.

First and foremost, there is nothing wrong with women and femmes aspiring toward motherhood; I do not seek to demean or degrade women and femmes who treat motherhood as a goal worth striving for.

Secondly, there is great pain, anger, and sadness in a mother losing her children, and those emotions should not be dismissed nor should her desire to have and nurture children be dismissed either. Lastly, feminism and motherhood are not mutually exclusive; desiring children and becoming a mother shouldn’t be treated as anti-feminist or misogynistic. A woman or femme should have the ability and freedom to make those major life choices of their own accord, not because government and lawmaking bodies order them to, and they shouldn’t feel ashamed for dreaming of motherhood out of fear of neoliberal feminists chastizing them for not optimizing themselves at the expense of their social and mental well-beings.

Get it? Got it? Good.

Now, back to “Multiverse of Madness.” Reducing Wanda’s complex identity to a near-supernatural obsession with the fate of her children is not uncharted territory for Marvel. In a 2005 blog post entitled “Womb Crazy!!!,” writer-director John Rogers pinpointed his key issue with that year’s major, “It Was Wanda All Along!”-centered Marvel Comics event story, “Avengers: Disassembled” (a.k.a. the prelude to the “House of M” storyline): “Wanda kills because she wants babies.”

As harsh as Rogers’ observation sounds, it’s not entirely inaccurate. In “Avengers: Disassembled,” Janet van Dyne – a.k.a. The Wasp – makes a flippant comment about motherhood that triggers Wanda’s suppressed memories of her lost boys – who were created via powerful magic – and a terrifying psychological breakdown that causes Wanda to lose control of her powers. Blaming the Avengers for the loss of her children, Wanda goes on a rampage, resulting in the deaths of some of her peers and allies – some by her hand, others at the hands of other heroes. In the end, Doctor Strange puts Wanda in a magically-induced coma, leaving her fate at the end of the arc ambiguous… until “House of M,” of course.

“What. The. Hell?” writes an incredulous Rogers. “Seriously, are there no female editors? No female friends of these writers [who went,] “Umm, you know, maybe this kind of sucks?” Good God, this sort of sorry-ass understanding of women’s internal motivations was supposed to have died out in the 1910’s, back when “hysteria” was a madness literally attributed to the presence – not even a disorder in, but [the presence] of – [women’s] parts.”

In other words, “Disassembled” and, later, “House of M” relying solely on an all-powerful female character beset with a case of “hysterical womb-madness” is not just lazy writing, it’s also dangerously sexist. It’s been seventeen years since Rogers published that blog post, but the gift of time has offered the most discerning reader the opportunity to understand where he was coming from in his critique of “Avengers: Disassembled,” and notice how it also applies to “House of M.”

Both stories, lauded as game-changers as they effectively altered the status quo of the Marvel Comics Universe for years, stripped Wanda of her agency and control over her life, mind, and powers. In the comics, Wanda has not only been possessed by dark forces multiple times, but she has also been mentally manipulated by various villains constantly. Moreover, Wanda’s memories of her children, let alone their physical existence, have been constantly manipulated by other powerful characters. (For example, “Disassembled” revealed Agatha Harkness totally wiped Wanda’s memories of her children, and, in retaliation, Wanda murdered Agatha and left her corpse for the Avengers to find. Comics can get pretty dark sometimes, folks.) The common thread between these stories is that Wanda only functions as “the crazy witch who wants to watch the world burn” rather than a major character possessing bodily, mental, and magical autonomy.

“Disassembled” and “House of M” use Wanda’s mental instability as inciting incidents but do not center around her.

Instead, “Disassembled” is about Captain America, who breaks up with Wanda at the start of the storyline and must work to find a way to stop his crazy ex-girlfriend from causing more chaos. Meanwhile, “House of M” is about Wolverine, who is thrust into an alternate universe where Wanda finally gets her sons back but at the expense of their friends’ lives and sanity, leaving him to set out and return the world to normal. Both stories hinge upon her losing control of her powers following an intense psychiatric response to trauma and grief, but Wanda is nothing more than a plot device, albeit a plot device whose iconic line has gone down in comics history as one of the medium’s most shocking moments (#progress?).

Neither “Disassembled” nor “House of M” offer readers significant, thoughtful insight into Wanda’s fractured psyche and the immense mental toll she has experienced in the wake of having her mind and powers manipulated by others for their own purposes. Both stories fail to examine what desiring children and a family means to Wanda, let alone the emotional impact of losing her boys and being told by numerous characters they were never real to begin with. All “Disassembled” and “House of M” do is scuttle Wanda’s genuine desire for family into the constraining box of idealized (read: oppressive), true womanhood. Getting her boys back is more than just Wanda’s primary goal in these stories; it’s her defining character trait.

In contrast, ‘WandaVision’ gives greater meaning to Wanda’s magical reconstruction of Vision, the magical creation of their children, and the Hex warping reality into an idyllic sitcom world. Wanda has not only lost her family – from her brother Pietro in “Avengers: Age of Ultron” to Vision (twice!) in “Avengers: Infinity War” – but she has also lost numerous opportunities to attain stability, community, and love. As weird as it might be for a woman to fall for a synthezoid, Vision was one of the few people who saw the good in Wanda and refused to view her as a bad guy when she believed herself to be one. In “Captain America: Civil War,” Steve’s love for Bucky outweighs his apparent concern for Wanda’s remorse and self-doubt in the wake of accidentally causing numerous civilian deaths in the film’s opening sequence. Although Clint Barton offered support to Wanda in “Age of Ultron,” he eventually chose to walk away from Wanda and the Avengers to be with his wife and children.

A lot of her peers and colleagues have friends, family (blood and found), and loved ones, but Wanda doesn’t. The least Hayward could have done in ‘WandaVision’ was let Wanda give Vision a burial fit for an Avenger and a husband. Instead, Hayward turns the bereaved Avenger away, continuing to experiment on Vision’s corpse (for reasons later revealed in the series), leaving a heartbroken Wanda hopelessly alone.

For “Multiverse of Madness” to reduce Wanda’s desire to reunite with Billy and Tommy once more to womb craziness does a disservice to how ‘WandaVision’ takes into account the intensity of the trauma Wanda has endured and how she has never been given the opportunity to grieve. Waldron’s screenplay contributes to the harmful pop culture trend of reducing women and femmes with children as only “mommies” rather than complex, adult humans whose interests and identities don’t exclusively revolve around their children. This limiting portrayal also harms the women and femmes who aspire to have children and a happy household since it frames such a desire as all-consuming and detrimental to their mental health. As if to say that if a woman or femme is unable to attain motherhood, then they have failed to emulate “true” womanhood and femininity. As a result, the cishet-patriarchal society is justified in punishing women and femmes for not adhering to such a misogynistic view of womanness.

Comic books may be dark, but the real world never fails to be darker.

No, The Problem Isn’t Wanda Being the Villain.

In the days after seeing “Multiverse of Madness,” my emotions around the movie soon distilled into the following cycle: from simmering rage to mild annoyance to joyfully being a hater about the movie online and in real life (I mean, anything to keep myself from being deeply disappointed by Sam Raimi and Michael Waldron’s lack of care and effort to properly integrate Wanda Maximoff’s story into the film), and back again. An interview with Michael Waldron published by IGN following the news of “Multiverse of Madness” breaking pandemic-era box office records in its first weekend, which isn’t all that new for Marvel Studios (see: “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings”), however, moved me from humorous hating to cortisol-invoking rage.

While discussing Wanda’s embrace of the Darkhold and the darker nature of her powers, Waldron offered what I could kindly describe as a half-hearted apology: “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. I hate it when characters I love do bad stuff too, but I’m glad it elicits a strong reaction. And she’s trying to get her kids, and I think she’s got a strong defensible point of view in her pursuit.”

I read it and re-read it, scoffing both times. Was he for real?

Not only was he offering up a non-apology apology, Waldron also (and dangerously) played ignorant to a damning aspect of his writing that yielded such a strong reaction to begin with. The problem isn’t that Wanda was the villain of “Multiverse of Madness.” In fact, Waldron did more than force an inauthentic villain arc on a character who could be viewed as more of an anti-heroine than a straight-up villain. Rather, in 2022, the year of Wong, our Mighty Sorcerer Supreme, an ignorant, mediocre white male screenwriter decided to transform one of the most powerful Avengers into yet another madwoman in the attic – er, uh… I mean, a madwoman in the multiverse.

Originally established in the pages of Charlotte Bronte’s “Jane Eyre” via the violent Bertha Mason, modern manifestations of the madwoman in the attic trope within cishetero-patriarchal popular culture twist women into characters with disturbed mental states that fall outside of traditional social norms. Madwomen become tools for exceptionalizing a binary representation of women and femmes that rewards women for being pure, virginal, and sane sweethearts while punishing the women who are mean, nasty, and mentally disturbed. Moreover, a woman’s craziness was utilized to reinforce the mistaken notion that men were naturally level-headed, while ‘crazy’ women were too emotional to make a rational decision. “Multiverse of Madness” shamelessly ascribes to this idea when establishing the dichotomy between Wanda Maximoff and Stephen Strange.

Strange is our courageous, morally upstanding, and skilled hero willing to save the multiverse at any cost, while Wanda is our murderous, rotten, and fearsome villain who must be stopped. Despite this surface-level hero/villain dichotomy, “Multiverse of Madness” contains flashes of a movie that illuminates a major fallacy behind that ideology: No hero is perfect, and no villain is completely devoid of components that we find to be heroic and or human. Since his debut within the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Strange has made a number of questionable decisions – including but not limited to helping a teenage boy brainwash an entire world into forgetting his superhero identity and handing over an all-powerful Infinity Stone to one of the Avengers’ most ferocious villains in the hopes it will give his colleagues the upper hand. Each of these decisions highlights arrogance as his most fatal flaw, something that is on full display throughout “Multiverse of Madness.” In fact, the climax of the film hinges upon Strange’s reckless disregard for the Illuminati’s warnings about the Darkhold and using the book anyway. Rightfully, Wanda once again calls him a hypocrite for embracing dark magic after earlier chiding her for using the Darkhold.

Yet, “Multiverse of Madness” implicitly communicates that Wanda’s desire to be reunited with her children and being pushed to the desperate choice of embracing dark magic is an inherently selfish one. Despite the fact that Strange himself has made a number of selfish and arrogant decisions throughout the franchise. After all, Strange’s path to the mystic arts began when he refused to live in a reality where he wasn’t a heroic neurosurgeon. Oh, and “Spider-Man: No Way Home” only happened because Strange disrespected Wong’s status as the Sorcerer Supreme and refused to heed his warnings about the forbidden brainwashing spell. “Multiverse of Madness” wants to suggest that Strange has got a long way to go when it comes to being a true hero, but that’s difficult to believe when it automatically paints its female antagonist as a bereaved, hysterical woman who is too dangerous to let live.

Moreover, “Multiverse of Madness” offers viewers zero insight as to why Wanda would turn to something so dangerous like the Darkhold to be reunited with her children. Wanda is so laser-focused on ripping an alternate version of her sons away from an alternate version of herself that, at no point, does the movie give a glimpse into her interior motivations. ‘WandaVision’ signified that Billy and Tommy Maximoff were more than representatives of Wanda’s desire to have a family and be a mother, but “Multiverse of Madness” reduces her to a deranged soccer mom playing magical hide and seek with a pair of sorcerers and a scared teenage girl. It’s the deliberate disrespect of a woman’s all-consuming grief and depression for me.

When Wanda logs in numerous hours in the Darkhold chasing the belief that it is the only way she can get her children back, Waldron’s screenplay writes her off as a woman so far gone that she can never come back to the side of goodness and rationality. When Strange grabs ahold of a variant of the Darkhold and performs yet another forbidden spell to get the upper hand, he is painted as a hero willing to do anything to save the multiverse. It’s a problematic dichotomy rooted in the very real-world and very sexist perception that a woman’s feelings and mental health are worth writing off as ‘crazy’ and ‘hysterical’ while a man’s actions are justified and understandable. Furthermore, it is a dichotomy that dictates who is more worthy of the audience’s empathy — hint: it’s certainly not the woman.

Goodbye, Wanda Maximoff.

I guess this is the part where I tell you about the end of the movie.

Right, but fair warning: you’re not gonna like it.

After spending much of the movie doing her best “Wicked Witch of the West meets Cordelia Chase” impression, “Multiverse of Madness” brings Wanda’s story to a frustrating end: she kills herself.

Yes, you read that correctly.

The strongest Avenger, the most powerful woman in the Marvel Cinematic Universe decides that the only way no one in the Multiverse will ever find the Darkhold is by bringing an entire mountain (one that contains a throne custom-made for the Scarlet Witch herself) down on herself. It’s a moment that comes after Wanda reunites with an alternate universe version of her boys, who are (understandably) terrified of her and call her a witch in-between calling out to their real mother: an alternate Wanda living in the modern-day suburbs, far removed from her days as an Avenger.

It’s a crushing moment where Wanda realizes that she has become the very monster she never wanted to be, the monster that Vision never saw her as when compared to the other Avengers. Yet, of all the characters in the movie, it is the alt-Wanda who actually reaches out to her and treats her with compassion. Alt-Wanda lets Our Wanda know that her boys will always be loved and that she shouldn’t worry about them.

Bringing down that mountain was supposed to be the visual representation of Illuminati Professor X’s parting words of wisdom before he is killed by Our Wanda: “Just because someone stumbles and loses their way doesn’t mean they are lost forever.” In making sure no one ever finds the Darkhold again, Wanda takes her own life, an act that is meant to be a stern rebuke of evil, a means of restoring balance and stability to the multiverse (which really should have been Strange’s job, but whatever).

Watching that whole scene go down (and remembering it now as I write this) made me so sick. I’ve gone down that path of wanting to take my own life before, believing that my death would be a blessing for my friends, family, and loved ones. Not only would I no longer be around to burden them with my pain, but maybe, in death, I would finally be free, too. Unless you’ve come perilously close to walking down the path of taking your own life, you can’t really comprehend the experiences and emotions of depressive suicidal ideation.

Call a spade a spade. Wanda’s suicide was not a heroic sacrifice, nor was it an act of redemption. It was a suicide triggered by grief, anger, loss, and pain. Once again, Wanda had to let go of the people and things that brought her stability, peace, love, and connection because… that’s what heroes are supposed to do.

Meanwhile, Strange acquires a gross new ability and his smokin’-hot, on-again/off-again girlfriend from the comics has arrived in the MCU – and she’s played by queer icon Charlize Theron. What a horrible end to a character who had been put through the proverbial ringer since 2015 – and what an unnecessary reward for a character who still fails to recognize how dangerous his arrogance and recklessness has proven to be for the entire multiverse.

“Multiverse of Madness” is not just a low point for Wanda Maximoff but for an entire slate of Marvel films and television shows that explore mental health in their stories. But, that’s not surprising. Instead, it is a reminder of whose stories are worth telling, whose struggles are worth giving space toward, and whose characterization is allowed to transcend the binary of hero and villain. If Marvel can make Marc Spector’s DID matter, there is no excuse for them to vilify Wanda’s mental health. If Bucky Barnes was allowed to reconcile with his past as the Winter Soldier and redeem himself, there’s no excuse for refusing to put Wanda on the same path.

In making Wanda’s mental health matter, ‘WandaVision’ sent the clear message that real and fictitious women and femmes’ mental health matters. It’s worth noting that because “WandaVision” centers around a thin, white, privileged, and cisgender female lead, it offers a limiting perspective on the intersection of gender and mental ability. It is absolutely important that Black, Asian, Latinx, Indigenous, Muslim, and mixed-race cishet, queer, and trans women and femmes get to be the focus of stories about mental health, grief, and trauma, too. Yet, “Multiverse of Madness” sends the message that this all-powerful woman’s actions during a clear mental breakdown is a justifiable enough reason to either have her be killed or let her kill herself.

This is the legacy of “House of M,” shot with IMAX cameras and projected onto huge silver screens filled with Dolby 7.1 surround sound speakers. Writer Lia Williamson’s final reflection on “House of M” can be applied to “Multiverse of Madness,” too: “It’s a story that says the mentally ill are dangerous, that we’re capable of horrible things and maybe we should be “put down” before those things can happen. This is its legacy — and it’s a bad one.”