Venturing into Enemy’s Territory?: K-Pop and Feminism

Ah, my prince! When are you gonna come save me?

Will you lift me in your arms and fly, like a white dream?

– I Got a Boy (Girl’s Generation)

Um, sure. Unsurprisingly, being a feminist and a fan of K-pop can be a rather trying endeavor.

A component of the Korean Wave (Hallyu), K-pop is the much-scoffed-at little sibling of K-dramas, with its ostentatious outfits, unabashed artificiality, and overall inattention to the actual music (I say this with all the love of a fan, of course). Simply put, it is pop in the Korean language. However, its potency as a cultural force worldwide has expanded its influence beyond its home country, compelling its audience, especially international fans, to confront different portrayal of culture and gender, resulting in a delicate balancing act between exercising cultural sensitivity and championing ideologies.

While there are many aspects within K-pop that are worthy of debate and critical analysis, including problems of cultural appropriation and oppressive work conditions, the enormous—pink, nonetheless—elephant in the room that entails urgent discussion is the misogyny and sexism present in the industry and its fandom.

The most obvious way this sexism is manifested would be the lyrical content of its songs. As much as K-pop is about the entire package—the dance performance, the fashion, the image projected by the “idols”—these are just vehicles for the songs they are selling to the public, even if the songs are often run-of-the-mill pop songs with recycled beats and generic lyrics. In fact, it is precisely the ultra-commercialization of the music that exposes the severity of the problem: These lyrics are written not in the voice of the composer but what the composer perceive as public sentiment. This is especially alarming as it suggests that these lyrics are but a mere thread in the wider tapestry of sexism. While both genders have their share of problematic lyrics, I contend that the sexism perpetuated in songs sung by female singers are much more potent than that of their male counterparts. When chauvinism is written in a male voice, it is usually much overt, and the sexism registers itself in our consciousness much easily. Yet, it is entirely too easy to overlook the implicit messages that perpetuate sexist outlooks on how a girl should act when they are nicely bundled in seemingly-innocuous, cutesy love songs.

This is especially obvious when we scrutinize the songs and performances that launched the representative Hallyu girl groups, Wonder Girls and Girl’s Generation to skyrocketing fame. Contrary to the innocent pastel colors and youthful girly outfits that displays legs rather than cleavages or derrieres, these groups, too, sell sex. It is, however, a different brand of sex from what Western audiences are used to. Instead, they infantilize themselves to emasculate males by pandering childlike, puritanical innocence not only visually, but also with the behavior of their on-stage personas, notably baby talk (aegyo, as it is called in Korean). The submissiveness and naivete they project appeal to the male audience, stroking their ego and fueling fantasies by inviting male protection, most infamously encapsulate by “oppa,” one of the first terms every K-pop fan learns. This phenomenon is appropriately coined as the “oppa culture.”

In short, the problem with “oppa culture” is, women acting like girls to please men is still sexual objectification at its core, even if minimal skin is shown. It only reinforces that females are weak beings that serve to gratify males and that males need to be “man” enough to “protect” them.

It would be a gross oversimplification to say that all girl groups in K-pop are marketed in accordance to this doctrine, though. 2NE1, Brown Eyed Girls, and Miss A are examples of girl groups that utilize “girl power” themes in their works. These concepts are a welcome change, even if they might feel artificial or even misguided at times. However, they are still mere occasional deviations from the persisting norm of sweet, cutesy and always-smiling girls with slyly concealed sexuality.

This is extremely problematic because these female singers are touted to champion Hallyu and they consistently reinforce such image in the content they distribute, strongly suggesting that this is what K-pop stands for, on issues about body image and gender stereotypes. This message is imprinted, consciously and subconsciously, into the minds of their fans worldwide, oftentimes pre-teen and teenagers.

However, an important question arises in the culpability of these female celebrities. Should they be blamed for the propagation of this sexism, or are they just victim of their circumstances?

To evaluate K-pop critically, understanding the nuances between content production and audience consumption within the industry content is vital. Running the risk of oversimplification, here are three points to consider about the structure K-pop:

First, K-pop is the enterprise of Korean entertainment companies, not the artists themselves. In contrast to the American pop scene, these record companies act as star-producing factories, with huge presence in every single step of the process. Currently, the three biggest companies, as measured by their revenue, are SM Entertainment, YG entertainment and JYP entertainment. Most of K-pop biggest acts outside Korea, such as Big Bang (YG), Girl’s Generation (SM) and 2PM (JYP), are housed by these three companies, though a handful of other smaller companies have succeeded in breaking onto the scene. These companies scout for promising talents, usually attractive adolescents, and recruit them to “train” with the companies’ in song, dance, rap, modelling and so on until they are deemed ready to debut. The “trainee system” demands a huge economic investment on the company’s part, and the artists carry this “debt” with them when they debut. One form of repayment is simply the sacrifice of artistry; therefore, works released by the K-pop singers are mostly dictated from the upper echelon of their companies. The unshocking truth is K-pop is about unadulterated profit. Art and self-expression? Not so much.

With female singers, this means they are often coerced into wearing revealing costumes they don’t like, dancing moves that makes them uncomfortable, and singing lyrics they don’t stand for. What these girl groups sell are essentially what their bosses think we, as the audience, would buy. The Korean entertainment industry, if not the society as a whole itself, is still largely patriarchal, with the CEOs of most entertainment companies being male. This means that females singers are often sculpted to fit the fantasies of middle-aged males who wield massive economic power over them. It is as icky as it sounds.

Second, K-pop has grown to be more than a simple label of a music genre. Instead, it a concept that simultaneously homogenizes and polarizes the industry by influencing the perception of what is profitable and what is not. This gives rise to a scale with hyper-commercialized idols that have little artistic autonomy on one end, and “artists”, whose works are usually self-composed and are catered to a smaller niche audience on the other end. Korean pop artists that then fall squarely in the artistic end of the spectrum, such as Eddy Kim or Akdong Musician, are often excluded from the term, their marketability underestimated, culminating in a self-fulfilling stereotype that K-pop is not only strictly shallow teenybopper music but also that music for female singers has to look and sound a certain way to be popular.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=9bZkp7q19f

Interestingly, most people’s idea of K-pop would be Psy of “Gangnam Style” fame, who isn’t typical of a K-pop singer at all. The success of “Gangnam Style” could be a force to show that diversity in K-pop is not a bad thing. Therefore, idols that occupy the grey area between these two extremes, who have creative freedom while retaining the style expected of K-pop, are important stakeholders in changing the atmosphere of the industry. Ten years ago, an idol group producing their own songs would be unthinkable. Nowadays, it is no longer a surprise, especially with the success of Big Bang and CN Blue. Change can happen within the industry, though it is slow and difficult. It is easy to see, though, that these producers are ultimately still overwhelmingly male. Some girl groups, like Brown Eyed Girls and 2NE1, are involved in the creative process, but the numbers pale drastically in comparison to their male counterparts. There simply needs to be more female voices within content production in K-pop. Songs for females tend to be a lot more empowering when a female is actually involved in its inception. For example, “Bloom” by Ga In that had lyrics written by female lyricist Kim Eana portrays female sexuality positively, for once.

This disparity, however, is not likely to change soon—after all, how does a female trainee learn to compose songs when all she has ever been taught to do is how to show off her “honey thighs” while dancing?

Third, K-pop thrives on fan culture, unsurprisingly, as rabid fandom loyalty consistently generates revenue, whether from the music itself, fan meetings, concerts, or the extremely profitable fandom merchandise. Companies encourage fan culture by highlighting their importance, giving fandoms their own names and an official color, among other things.

It is, then, obvious that we, as consumers, possess considerable power in influencing the content produced. Therefore, beyond evaluation of the artists themselves, we need to turn the metaphorical camera back onto ourselves and evaluate our own attitudes.

A unfortunately common example of double standards is the different things the media and the audience focus on when a singer comes out with something new is a common example of the double standards. Male singles garner praises for their efforts in writing their own songs or having intricate dance choreography. However, for female singers, all that is talked about is which body part was showcased in the their dance or how her latest diet regime turned out. 2NE1 and Brown Eyed Girls are frequent victims of body shaming for accepting – or not accepting – plastic surgery.

Even beyond explicit sexist actions as mentioned above, Oftentimes, we make offhand remarks and comments so ingrained in us that we don’t even see how problematic it is. Offhand remarks that shames the singers for plastic surgery like “I can never get their names right – they all look the same” are just as detrimental towards the feminist cause as sexist lyrics.

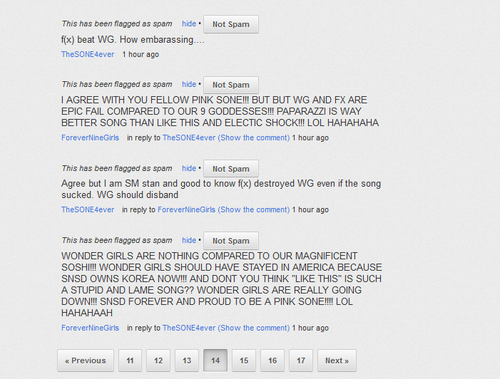

This serves to show how the cycle ultimately works — the celebrities disseminate ideologies about gender and body image which is then regurgitated by the audience to exercise leverage on the trend of the industry. Even worse, fan mentality (“You’re just jealous of my angels!”) only impedes critical

discussion of social issues in K-pop. Case in point: Go to the comment section of any K-pop video on Youtube.

Undoubtedly, there are K-pop songs that are not merely the sterile products conceived in a boardroom filled with leering middle-aged men, songs that embody a sincere message meant to educate, inspire and empower. However, the bottom line is that these songs are the rare, rare exceptions and never the rule; the chasm between feminist thought and K-pop does seem bleakly irreconcilable. Honestly, it would probably be healthier for me to walk away and invest my emotions elsewhere.

Yet, I don’t – because whether it’s about feeling ugly or the oddly empowering triumph of singlehandedly exterminating a cockroach, when K-pop gets it right, it gets it so right.

These little moments of emotional connections are universal, transcending language and culture to remind us we’re not alone. So, yes, even though this is an industry that constantly tries to peddle ideas that I find repulsive to me, I am still a fan of K-pop, and that means I will never stop advocating change and making my voice heard about these problems .