Zoe Leonard Analogue: Self-Aware or Blissfully Ignorant?

Image credits to Hauser & Wirth Exhibitions

Artists and art appreciators alike have lately been discussing the role that art galleries and museums play in displacing and harming the communities they supposedly serve.

Institutions like the Brooklyn Museum and art galleries in Boyle Heights have been subject to criticism for their aid in the displacement of local residents. I couldn’t help but think of these movements when I visited Hauser & Wirth on a recent Sunday afternoon to view Zoe Leonard’s current installation, which focused on the effects of gentrification right outside Leonard’s studio in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, from 1998-2009.

Zoe Leonard Analogue is certainly one worth exploring, regardless of your personal knowledge on the subject matter.Though this is its first introduction to Los Angeles, this particular collection of photographs was previously entered in other museums such as the Museo Reina Sofia and the MoMA. According to the Hauser & Wirth website, Leonard’s exhibition touches on themes “of gentrification and the exchange of commodities as an extension of colonialism” while also making statements on relating it to globalization through photographs of Essentially, Leonard’s photographs of storefronts in the Lower East Side and markets from other parts of the world are meant to be visual representations of a well-known fact: today’s gentrification is essentially an extension of colonial projects such as Manifest Destiny and slavery.

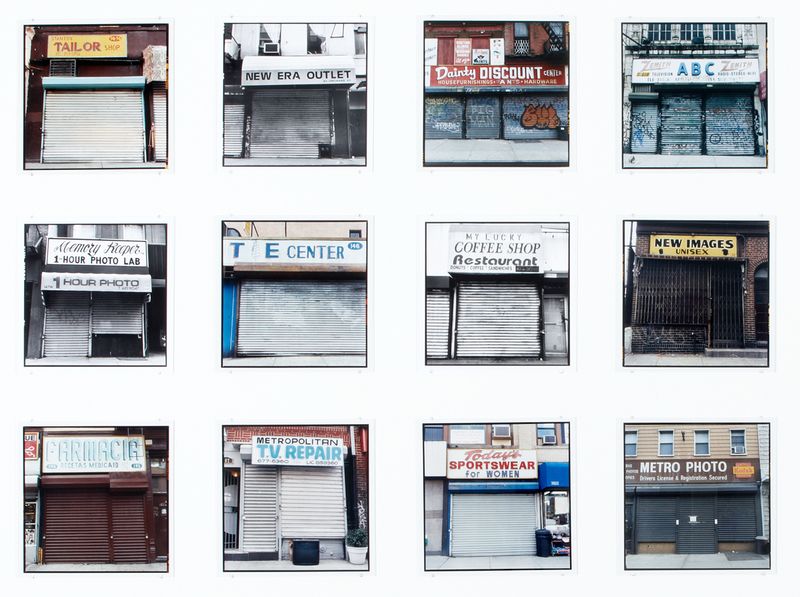

When I emerged through the doors into the gallery space, I was immediately entranced by Leonard’s work. Her photographs are arranged somewhat randomly, but also often by subject matter; occasionally they are in sets of six and sometimes in sets of twelve to sixteen. Certain photos are in black and white, while others are in color. I actually really appreciated the fact that the exhibition wasn’t highly organized or curated; there wasn’t a set path or linear movement to the pieces, which actually seemed to lend itself to the rapid (and often random) pace of gentrification that I have personally observed in different parts of Los Angeles and the country.

Leonard’s technique in the photographs is quite beautiful, particularly with regards to her color choices. There was a perceptible lack of color coordination in general; though I could not find a pattern amongst the black and white photographs versus the ones in color, these photographs did draw my eye inward when they were arranged alongside each other. The disparate colors of certain photographs reflected the grim nature of economic displacement, while the ones in color illustrated that despite the blows these communities suffered, life and hope still persists. Moreover, none of the photographs were dated or contextualized by location; this, again, engaged me to some degree and further exemplified the nature of gentrification as something that knows no bounds. But at the same time, I was a bit puzzled, as I think that some context would have been helpful in actually tracing the process of gentrification in Leonard’s community.

The actual subject matter of the photographs was very simple and not necessarily what a viewer would consider aesthetic on its face, but Leonard did an incredible job transforming these rather grim storefronts into anti-colonial and rather optimistic statements through interesting angles and bright colors that saturate the photograph. Many of the most appealing pictures were actually of open businesses, presumably on the brink of financial ruin. A series of photographs featured old, dusty televisions and stained mattresses for sale, displaying the desperation of many of the businesses in these communities to survive through any means necessary.

Many of the photos were inundated with branding and commercial names – such as Coke or Kodak – featured proudly atop dilapidated stands or buildings, emphasizing the destructive nature of capitalism on these communities. Storefronts that were pictured and open for business often had signs in their windows stating whether or not they accepted food stamps or W.I.C.. In one chilling piece, a sign that stated the store’s acceptance of W.I.C. was placed next to a tall pile of cleaning chemicals, explicating the issue of food deserts and the lack of proper nutrition provided to those receiving food stamps. Among the most striking pieces was one that featured the front of a beauty salon with a sign that stated it could provide “True Desires for Beauty;” the sign also featured pictures of black women with relaxed or straight hair. This is clearly Leonard’s criticism of the infiltration of Eurocentric beauty standards for women in both colonial and gentrified areas.

As promised, the exhibition did feature lots of photographs of closed businesses. The signs of these businesses featured a variety of languages, emphasizing the gentrification doesn’t touch just one particular group, but almost anyone in low-income areas. One of the closed storefronts was a law office, which I believe was a meditation on the lack of access for low-income residents to proper legal representation; a photo of a closed fresh meat market also seemed to reiterate earlier points about food deserts and proper nutrition for those of lower socioeconomic statuses.

Finally, there were the photos of marketplaces around the world. This was the one part of the exhibition that left me a little underwhelmed; without the context of a location or date, it was initially hard for me to determine that these photos of suit jackets suspended in midair were from places other than America. It was only through guesswork and subtle context clues, like a dirt road, that I was able to gather that these were in fact from places outside of the U.S. rather than flea markets on the Lower East Side. Ostensibly, the items for sale in the photos outside of the U.S. are supposed to be similar to the items for sale in the photos of the Lower East Side markets, and thus we are supposed to draw a comparison between colonized countries and our own poor communities. But, again, without the context of a location or date, this connection is not assured or properly received by the viewer, though it is a vailent effort on Leonard’s part.

It’s clear that Leonard’s photographs are infused with a great deal of meaning and subtext. However, I still find it difficult to accept the circumstances under which the exhibition was framed. On my way home from the gallery, I accidentally took a wrong turn and wandered into Skid Row. There were so many homeless people that it was difficult for me to even walk on the sidewalks; at one point, I had to walk in the street. To reiterate, this was within walking distance of a gorgeous gallery filled to the brim with affluent hipsters. I was surrounded by Yves Saint Laurent one minute and the next I almost stepped in human feces. The irony was not lost on me that Hauser & Wirth is in a highly gentrified area, but I fear that it was lost on my fellow gallery patrons. Perhaps Leonard’s intention was to display her work in a space that would reach the very people she was trying to indict, as she has a similar exhibition on right now at the MOCA but chose to feature this collection at H&W. Or maybe it was just a coincidence? Honestly, I found it odd that there was no artist statement or description other than what was found in the museum pamphlet or online which would have helped me understand her intentions a bit better. Thus, I cannot concretely say whether or not I fully enjoyed this exhibition, because whether or not Leonard was aware of this irony is, from my view, crucial in determining the quality of her work.

The photographs are beautiful – I don’t want to take away from that. Leonard is a talented artist and obviously has an eye for making what is not typically seen as aesthetic or beautiful, like a graffitied metal storefront, into a captivating statement on capitalism and colonialism. I just can’t decide if these statements were actually taken to heart by Leonard, Hauser & Wirth, or those that viewed the exhibition. I don’t think this should limit people from viewing Leonard’s work, as I do think that meaning and an understanding of gentrification can be derived from the photographs, just so long as they are isolated from the poor framework of H&W. This is sort of a challenge, as there is not really an affordable published version of the work (another irony) available for purchase, but nevertheless I urge everyone to attempt to view it via previous art reviews. In this way, any viewer of Leonard’s work therefore will properly extrapolate the anti-colonial and gentrification claims made by the collection to gallery spaces themselves; after all, art should be about criticizing oppressive institutions, regardless of whether or not they purport to be allies of the surrounding communities.