All Women Are Like That: Sexism in Mozart’s “Così fan tutte”

It is never surprising to find instances of gender inequality and problematic constructions of women in pop culture. However, I regret to say that the lofty, otherworldly sphere of high culture is not exempt from blatant instances of sexism and unforgivable misogyny either. Last month, I had the pleasure of attending one of Mozart’s most beloved operas, “Così fan tutte.” Although it was my first time seeing the opera, I have known the infamous English translation of the title for years. In Italian, the title means “all women are like that.” Of course, I was intrigued by the cryptic title, but had a suspicion that the opera would inevitably generalize femininity and feature an ugly sexism masked behind a breathtakingly beautiful set and celestial music.

It is never surprising to find instances of gender inequality and problematic constructions of women in pop culture. However, I regret to say that the lofty, otherworldly sphere of high culture is not exempt from blatant instances of sexism and unforgivable misogyny either. Last month, I had the pleasure of attending one of Mozart’s most beloved operas, “Così fan tutte.” Although it was my first time seeing the opera, I have known the infamous English translation of the title for years. In Italian, the title means “all women are like that.” Of course, I was intrigued by the cryptic title, but had a suspicion that the opera would inevitably generalize femininity and feature an ugly sexism masked behind a breathtakingly beautiful set and celestial music.

The opera grapples with the notion of infidelity and pins the blame of failed love on the unreliability of women. Guglielmo and Fernando, the opera’s male protagonists, are convinced by their cynical comrade, Don Alfonso, that their fiancées will prove to be unfaithful if given the chance. Don Alfonso’s reasoning rests upon the spurious claim that their fiancées will cheat, not because of any fault in the relationship or in their characters, but because they are women. The men then devise a ruse to “test” the women’s fidelity. Don Alfonso bets that the women will fall for the men if they are disguised as swarthy and hypersensualized Albanians. By claiming that the men have been summoned to war, he seizes the opportunity to dupe Fiordiligi and Dorabella, the unfortunate fiancées in the opera. With the help of the animated and cunning maid Despina, he successfully entraps these women in his carefully crafted scheme in order to assert his sexist and misogynist agenda. Of course, comedic opera plots can be rather absurd and unbelievable, but “Così fan tutte” truly pushes the boundaries. Sexism is neither funny nor brilliant, even when it is in the world of highbrow opera culture and surrounded by the genius melodic genius of Mozart. The women, despite their initial staunch resistance, succumb to these seductive strangers because these men are relentless in proving them unfaithful; the men indulge themselves in a self-fulfilling prophecy. Indeed, the women fall in love within twenty-four hours, and even demand a marriage contract that Despina, disguised as a male lawyer, provides. Therefore, Don Alfonso is proven correct in his predictions about the women, and misogyny reigns supreme by the end of the opera. When the men “return home” and appear again as Guglielmo and Fernando, they forgive the women because they believe it is a simply a woman’s nature to be unfaithful and fickle. They excuse their fiancées’ actions by using a trite justification for infidelity: these women should be forgiven because they simply cannot help themselves.

Not even the music of Mozart could save this dreadful plot. The opera not only depicts the women as unfaithful, but as easily swayed and fooled. The fact that they fall for these “Albanians” implies that the ladies are too obtuse to recognize their own lovers. Women are thus signified as naïve, gullible, and easily manipulated. In addition, the two aristocratic beauties are extremely unlikable. They are spoiled, demanding, melodramatic, enjoy being victims, and make their poor maid Despina’s life absolutely miserable. However, the opera truly errs in its battle of the sexes test for infidelity. The opera’s final verdict, “all women will cheat,” is analogous to the female complaint that “all men are dogs.” Both statements are broad, unfair generalizations, and the opera fails to realize that fidelity is a matter of individual character. Over two hundred years later, I beg Mozart to realize that no, not “all women are like that.”

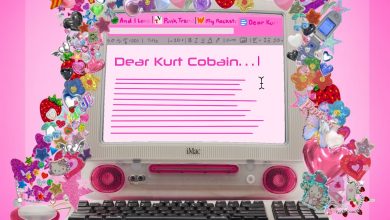

Check out the final scene of the opera, which features the delightful Despina’s cross-dressing as a lawyer and the return of the men to their brides-to-be:

I can understood why you might feel this way, but I think you’re underestimating Mozart’s treatment of women. Even in the thoroughly creepy “Don Giovanni,” it’s the female characters who leave the deepest impression, and in a positive way, I should add.

What exactly is the problem with the “that” of the title? As I understood it, the opera was a critique of the double standards applied to men and women. That is, if men have the “right” to infidelity, women should have the same right too.

Also, is it really so bad to shatter the silly “goddess” image the men had about their fiancees before their little experiment, and to discover that women have desires just as real as their own? Mozart’s views (and those of his librettist, da Ponte) were ahead of his time, and I believe that it’s a liberating rather than sexist opera.

Interesting perspective, Hans! I like that you bring up how the opera potentially humanizes women and reveals that women do indeed possess a sexuality. However, I can’t seem to dismiss the opera’s misogynistic undertones. Besides, infidelity shouldn’t be practiced by either sex!

Additionally, I do believe Despina vindicates the opera-she was my favorite character.The vacuous female protagonists undermine any liberating feminist agenda this opera may have. Instead, these women do not have healthy sexual appetites, but are portrayed as fickle, newfangled monkeys that are chasing novelty and the “next best thing.”